- Portugal

- Johannes Brahms

- Reinbert de Leeuw

- Boulez

- Charpentier

- Patric Standford

- Jordan

- Franz Schreker

SPONSORED: DVD Spotlight. Olympic Scale - Charles Gounod's Roméo et Juliette, reviewed by Robert Anderson.

SPONSORED: DVD Spotlight. Olympic Scale - Charles Gounod's Roméo et Juliette, reviewed by Robert Anderson.

All sponsored features >>

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

A Real Triumph

GIUSEPPE PENNISI experiences Puccini's 'Tosca',

live in HD at the inauguration of La Scala's

2019-20 opera and ballet season

On 7 December 2019, La Scala's 2019-2020 opera and ballet season was inaugurated with Giacomo Puccini's Tosca as part of a program designed by its musical director Riccardo Chailly to re-evaluate philological versions of Italian operas from the first decades of the twentieth century. As a matter of fact, Tosca is more than an important opera of the last century.

14 January 1900 is considered as a turning point in Italian music - the true beginning of twentieth century music and especially of the Italian-style music drama. It is the date of the debut of Giacomo Puccini's Tosca on a libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica in what was then called the Teatro Costanzi and now is part of Teatro dell'Opera di Roma.

Set design for Act II of Puccini's Tosca (Palazzo Farnese) in 1900 by German advertiser, costume designer, illustrator, painter and constume designer Adolf Hohenstein (1854-1928)

It was a great triumph and had long-lasting implications for theatre in music, not only in Italy, but elsewhere too. It moulded, for example, opera in the United States and influenced that of many European countries. It was also perhaps the penultimate opera in which Puccini found a libretto that lived up to his skills: The last one is, in my opinion, Il Trittico, in particular the two acts (Suor Angelica and Gianni Schicchi) for which the librettist was Gioacchino Forzano.

Tosca needs no introduction. The opera is one of Giacomo Puccini's workhorses, as well as one of the world's most performed music dramas. The plot unfolds in a single day and on a precise date - 14 June 1800 - around the misleading information that reached Rome about the outcome of the battle of Marengo during the Napoleonic campaign to conquer Italy. At that time, communication left much to be desired; in the afternoon, news came to Rome that Napoleon had been defeated and celebrations were organized a little quickly to thank God and the anti-French coalition. It was what is now called fake news. Late at night, the correct information arrived: the coalition had been beaten and Napoleon was on his way to Rome. During these hours, the sadistic head of the Roman police, Scarpia, attempts to rape the singer Floria Tosca, who is in love with the liberal painter Mario Cavaradossi. Tosca stabs and kills Scarpia, but Cavaradossi is shot by a firing squad of Scarpia's men. The desperate protagonist throws herself into the Tiber.

The Washington Post's long time music reviewer, the late Paul Hume, called Tosca 'a drama of blood and guts'. It's an unjust comment because the work is full of musical innovations that have marked the history of music and still fascinate the audience: a symphonic tapestry with key themes, melodious declamation that results in airs and arioso, an excellent balance between orchestra and stage, and a fast tense rhythm of the action.

In the stagings of these years, events are often moved to recent times, especially those of fascism - for example, in the stagings of Jonathan Miller, Peter Sellars, Robert Carsen and Pierluigi Pizzi. In 2015, Teatro dell'Opera di Roma presented a Tosca production as staged on 14 January 1900. It has been a great success and has entered the repertoire: every year, it is staged fifteen to twenty times on non-subscription evenings. At La Scala, the last two productions were signed by Luca Ronconi in 1997, characterized by almost abstract structures, and Luc Bondy in 2012 - a co-production with the Metropolitan Opera and the Bavarian National Opera of Monaco - who was booed in New York and did not cause great enthusiasm in Milan.

For health reasons I could not reach Milan. Thus this review is based on a live HD cinematic rendering of the performance.

This production – direction: Davide Livermore, sets: Giò Forma, costumes: Gianluca Falaschi, lights: Antonio Castro, projections: D Work - is both traditional and innovative. It is traditional because in its colossal grandeur it relates to the famous one by Franco Zeffirelli for the Metropolitan Opera House and seen, moreover, also in many other theaters. It is innovative because it uses all the scenic and technological machinery of La Scala to give the action a fast and a cinematic pace. The audience at the inauguration loved it.

A scene from Puccini's Tosca at La Scala Milan. Photo © 2019 Brescia e Amisano

Chailly used the original score, that of 14 January 1900, several times retouched by Puccini himself, not only because he was a perfectionist but because he revised the writing, especially for the orchestra, depending on the performers. Only very attentive and experienced ears can feel the differences. A connoisseur notes them in the finale of the first act, the Te Deum. Chailly, a true fan and scholar of Puccini, emphasizes the continuous symphonic orchestration in which a dozen themes intertwine with great skill. La Scala's orchestra did wonders, especially at the beginning of the third act when the Roman dawn is presented with a stereophonic game of bells.

Anna Netrebko's debut in this role at La Scala was highly anwaited. She unleashed a velvety and pasty voice and great stage skills as a true 'diva'; she deserved the long open-stage applause after Vissi d'Arte.

Anna Netrebko in the title role of Puccini's Tosca at La Scala Milan. Photo © 2019 Brescia e Amisano

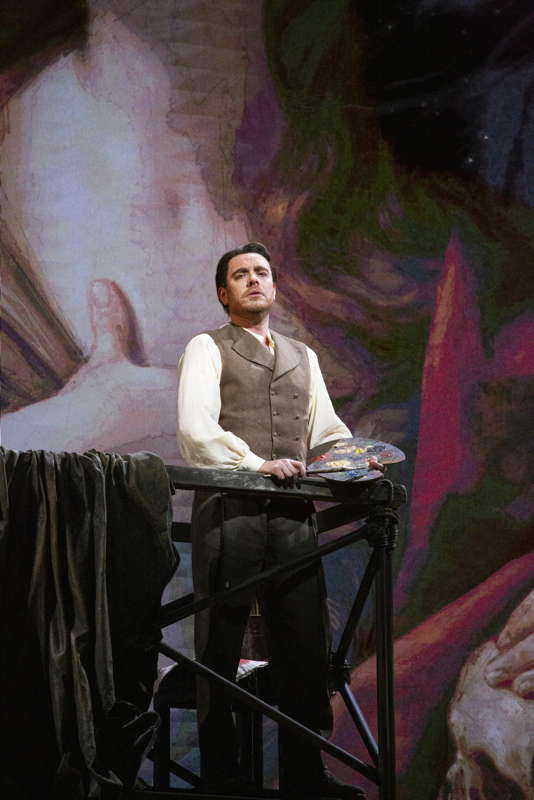

Francesco Meli began his career as a light lyrical tenor and for years successfully played tenor spinto roles - especially Verdi. His Cavaradossi has excellent phrasing, good legato and sharp, clear and transparent high range; he was applauded open-stage after E lucevan le stelle.

Francesco Meli as Cavaradossi in

Puccini's Tosca at La Scala Milan.

Photo © 2019 Brescia e Amisano

Luca Salsi is a perfect Scarpia, both vocally and scenically.

Luca Salsi as Scarpia in Puccini's Tosca at La Scala Milan. Photo © 2019 Brescia e Amisano

There were good interpreters of the minor parts. The performance was a real triumph.

Copyright © 8 December 2019

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy