An Autumn Trilogy

'Norma', 'Aida' and 'Carmen' in Ravenna,

reviewed by GIUSEPPE PENNISI

The Ravenna Festival's Autumn Trilogy has been an event for ten years: three operas linked by a theme. They can be seen and heard over three days in a row; the cycle is replicated three times. Sometimes they are in co-production with other theaters; sometimes, they are rented out after the first Ravenna opening. Singers are often young. Young people make up the chorus and the orchestra - the Cherubini Ensemble created by Riccardo Muti and renovated every four years. The Alighieri Theatre has the ideal size and acoustics. The most eloquent sign of the success of the operation is the growing presence of foreign audiences, who come to Ravenna for the Trilogy and in the three days, can admire the beauties of the city and its monuments. It is essential to book early.

From a musical point of view, there is philological rigor: no cuts, original language. Another important aspect is that 60% of the cost is financed with its own funding - tickets, sponsors, royalties - and only 40% with public subsidies - a percentage of private funding that is surpassed in Italy only by La Scala.

This year the Trilogy (1-10 November 2019) was centered on the woman, on love and on death: Norma by Vincenzo Bellini, Aida by Giuseppe Verdi, and Carmen by Georges Bizet. A brave choice, because Norma is considered so impervious that it has not been seen at La Scala for forty-two years. In my memory, the original version of Carmen has not been staged in Italy for decades. Norma and Aida are directed by Cristina Mazzavillani Muti and Carmen by Luca Micheletti.

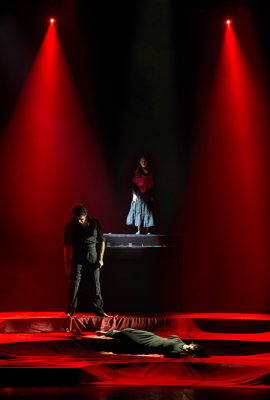

Antonio Corianò as Don José and Martina Belli

in the title role of Bizet's 'Carmen'

in Ravena. Photo © 2019 Zani/Casadio

I saw and listened to Norma on 5 November 2019. The staging does not give in to the temptation to move the setting to other times and places - as at recent productions in Salzburg and Stuttgart - but strictly follows the libretto. The sets and the visual design (Ezio Antonelli), the costumes (Alessandro Lai), the videos (Vincent Longuemare and Davide Broccoli) take us to the Gaul occupied by the Romans. Very telling the description of the forest and very good the special effects, especially in the invocation to the moon in Casta Diva. The orchestra conducted by Alessandro Benigni is, as in Bellini's time, essentially a support to the voices. The chorus was led by led by Antonio Greco in the three operas. The choreographic elements are handled by the DanzActori Autumn Trilogy.

Norma is above all an opera of voices. At the La Scala debut in 1831, two 'bel canto tigers' of the time were in the two main roles, Giuditta Pasta and Giulia Grisi, two sopranos of great renown. The practice is now of entrusting the role of Norma to a soprano and that of Adalgisa to a mezzo, but the two roles can also be reversed. In this edition, Norma is the Korean Vittoria Yeo, whose career in Europe was launched in Ravenna in the 2013 Trilogy, and Adalgisa is Asude Karayavuz, of Turkish nationality, technically a mezzo soprano with dark coloring, who has often sung soprano roles. Their duet Mira o Norma in the second act was a context of skill and agility that deserved open-stage applause. The male protagonist, the tenor Giuseppe Tommaso, was affected by acute inflammation both on the evening of the opening night - 1 November 2019 - and at the performance I attended; therefore, he only played the part that was sung, from one side of the stage, by the young Riccardo Rados, who showed an excellent vocality and deserved applause. Oroveso is the solid bass Antonio Di Matteo. There were ovations for the two protagonists and applause for all.

A scene from Bellini's Norma in Ravenna with, at the centre, Vittoria Yeo in the title role. Photo © 2019 Silvia Lelli

The Alighieri Theatre, where I saw and listened to Aida on 6 November, has a size and orchestral pit similar to those of the Cairo Opera House in Verdi's time. Thus, there was the opportunity for a real philological operation: to do away with the colossal Aida of recent practice and to attempt to reproduce the original more intimate 1871 Aida. The philological operation was half-baked. The creative team was basically the same as in Norma: Cristina Mazzavillani Muti for direction and Ezio Antonelli, Vincent Longuemare, Davide Broccoli, Anna Biagiotti for sets, videos, lights and costumes. From a dramaturgical point of view, the production is only partly philological. The opera is divided into four acts, as in Verdi's time, and not in two parts, as is usual now in order not to make the evening excessively long. However, while the third and fourth acts are 'intimate', in the first and second, the projections attempt to recall a colossal production. In addition, between the first and second scene of the fourth act, a Middle Eastern funeral lament is introduced, sung by the mezzo soprano Simge Büyükedes. However beautiful and interesting it might be, it has nothing to do with Verdi's opera.

Let us go to the most strictly musical part. The Cherubini Ensemble was conducted by Nicola Paszkowski, a top class director already heard several times in Ravenna and elsewhere. The balance between pit and stage was excellent: it is rumoured that the preparation of the staging and some rehearsals were helped by the creator of the Cherubini, Riccardo Muti, who recently directed beautiful versions of Aida in Chicago and Salzburg.

The interpreters, in general, were good. Amneris was the young Brazilian Ana Victaria Pitts, a mezzo of great vocal and acting skills; her Italian career is just starting but I am sure we will hear more of her. Radames was Azer Zada from Baku, also at the beginning of his career with an excellent center register and a powerful volume. Amonasro was the Romanian Serban Vasile, already known and appreciated in his homeland. Andrea Vittorio De Campo (Ramfis), Adriano Gramigni (the King) and Maria Paola Di Carlo have been singing for years in Italian theatres. What about the protagonist? Aida is the Lithuanian Monika Falcon. Not a great stage presence, and with a tendency to push excessively on the treble. There was warm applause.

A scene from Verdi's Aida in Ravenna with, at the centre, Monika Falcon in the title role and Serban Vasile as Amonasro. Photo © 2019 Zani/Casadio

The best was the final opera of this trilogy: a production of Bizet's Carmen (which will be seen in Lucca and Ferrara, whose theaters co-produce it) in the original version that debuted in Paris as opéra comique with dialogues spoken between the various numbers and, of course, in French. The orchestration is rougher than that modified by Ernst Guiraud for the Vienna Opera and now generally accepted. However, it is more fascinating and has nothing of the 'verist' colour of the productions of Carmen that raged until the end of the nineteen eighties and that are heard often today. It recalls polyphonic madrigals - the second act quintet. It is also leaning towards an expressionism that never took root in France, but created a great school in Germany.

Another significant aspect is that the stage director is Luca Micheletti, an eclectic artist who follows, at the same time, multiple careers in the world of entertainment: not only is he an award-winning stage director, actor and mime in dramas but he is also a classy baritone. He plays, in fact, the role of Escamillo.

Martina Belli in the title role of Bizet's 'Carmen'

in Ravena. Photo © 2019 Zani/Casadio

The setting is a twentieth-century Spain of mischief, prostitutes, lemons, brothels, and smugglers, in which the good soldier Don José lets himself be misled and ruined by what seems to be his first sexual experience. The only positive character is the innocent Micaela. There are no projections but scenic elements (by Ezio Antonelli) in which black, grey and red dominate (in Alessandro Lai's costumes too). There was a high-level acting by the protagonists, minor roles, extras and the chorus. The orchestra conducted by the Belarusian Vladimir Ovodok, who I met a few years ago right here in Ravenna, is dazzling: full of colours and rhythm, it builds an intense drama that the audience follows with passion. Among the protagonists. special notice needs to be taken of Martina Belli - a feline Carmen with a dark coloratura and a large register, Antonio Corianò - a young Don José with a tenor 'spinto' timbre, and Luca Micheletti - a cynical Escamillo with a robust voice. On the evening of 7 November 2019 at the performance I attended, Elisa Balbo (Micaela) was less convincing than at other times that I've heard her sing. There were very good singer-actors in the many minor parts, and accolades and ovations at the end.

Copyright © 10 November 2019

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy