DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

Sacred and Secular

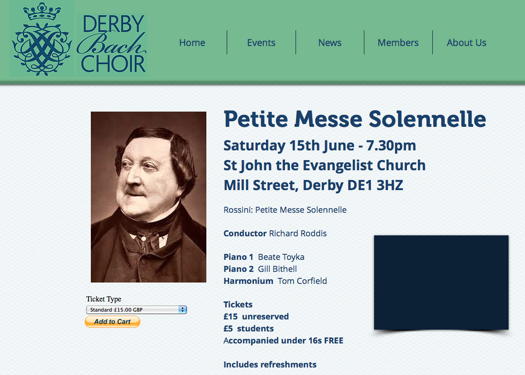

Rossini's 'Petite Messe Solennelle' from

Derby Bach Choir, Richard Roddis and friends,

appreciated by MIKE WHEELER

Over 150 years on, Rossini's Petite Messe Solennelle still has some of us scratching our heads as to exactly what kind of work it is. The old canard of it being neither little nor solemn can easily be disposed of: it was written for a small private occasion, with an ensemble of just twelve singers; and 'solemn', in this context, has nothing to do with its expressive quality, but is simply a technical term meaning that the entire text is sung. There is, no doubt, a tongue-in-cheek element in Rossini's title, but at least no-one, as far as I know, has tried to call the work his greatest opera, by analogy with the misfortune that overtook Verdi's Requiem.

Derby Bach Choir and conductor Richard Roddis rounded off their current season - St John's Church, Derby, UK, 15 June 2019 - with a performance that had me re-assessing the work from the ground up, and that can only be a good thing. There was a tentative-sounding start to the Kyrie that seemed entirely apt. And while the opening of the Gloria was properly forthright, the 'Laudamus Te' came as a reminder that the work has its solemn, or at least serious, moments. Then a number arrives like the jaunty tenor aria 'Domine Deus', and everything's coming up sunshine again, with, on this occasion, Beate Toyka and Gillian Bithel pointing up some delectable details in the two piano parts - a cheeky run here, a bouncy rhythmic figure there. Their bubbly contribution to the 'Cum Sancto Spiritu' fugue undercut any tendency for the music to take itself too seriously, and by the end it was all going (if you'll pardon the expression in this context) hell for leather.

Online publicity for Derby Bach Choir's 'Petite Messe Solennelle' performance on 15 June 2019

The performance of the Credo had similar virtues - darkly meditative in the 'Crucifixus', the 'Et Resurrexit' filled with explosive fortissimo outbursts.

The Sanctus is preceded by the instrumental 'Prélude Religieux, pendant l’Offertoire', which Rossini is believed to have included just before the first performance. It's a curious piece, with a sombre opening that turns lighter and more flowing. After a piano introduction, this is where the harmonium, which has mostly been supporting the singers until now, comes into its own. Tom Corfield gave the piece affectionate treatment, on an agreeably bright, reedy-sounding instrument. The flowing account of the Sanctus and Benedictus was a reminder that Rossini's way with the mass text is not that far from Haydn's.

Among the four well-matched soloists, Jeremy Leaman's dark, rich bass complemented Tom Stanyard's open, Italianate tenor, whose jaunty, easy delivery of 'Domine Deus' just lacked the last degree of swagger. Soprano Anabelle Popper's mezzo-like quality brought urgency to the 'Crucifixus' and the climax of the hymn 'O Salutaris Hostia'. Contralto Natalie Winsdor was sounding tragic depths by the end of the Agnus Dei, when we realise that the tone of the work has been getting progressively darker all this time.

Gioachino Rossini in about 1850

So was Rossini having the last laugh, or does his half-apologetic, half tongue-in-cheek note to the Almighty, confuse rather than enlighten? Does it matter? Or is he just showing us that in the long run sacred and secular don't live in separate boxes?

Copyright © 21 June 2019

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK