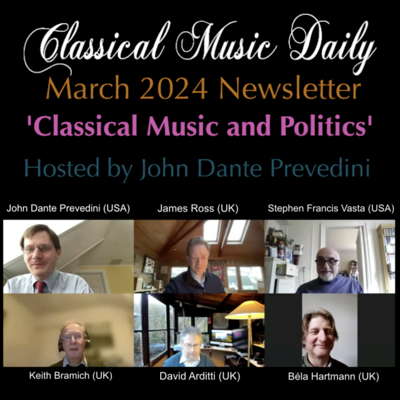

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Politics, including contributions from Béla Hartmann and James Ross.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Politics, including contributions from Béla Hartmann and James Ross.

In Search of Musical Text

ONA JARMALAVIČIŪTĖ talks to

Austrian-Czech composer Šimon Voseček

Austrian-Czech composer Šimon Voseček

The Austrian-Czech modern music composer, actor, playwright and former dancer Šimon Voseček (born 1978) says he has spent most of his life on the stage. His creation is characterized by a narrative of history, dramaturgy, experimentalism and emotional impact. Today he is one of the most prominent contemporary opera creators in Austria. I interviewed the composer about musical life today and his life and creative work.

Ona Jarmalavičiūtė: How do you start composing? What steps do you take to implement a musical idea?

Šimon Voseček: It is quite difficult to answer this question because the process is not very clear to me. Indeed, I have a lot of delay at the beginning of the creative process. There is no pre-preparation, I write a score from the beginning – I do not sketch or use tables, nor do I write descriptions of pieces. Only when I start writing the beginning of the composition can I imagine how the rest of the work will look. Then I start trying different ideas, looking at it and making decisions. I have a lot of freedom and improvisation in my creative process.

During my studies I tried to create a constructive principle, but for me such compositions simply do not work. The realization of musical ideas comes very slowly for me. I highlight what I want to say over the years, so I ponder them for a long time in my mind before I start composing.

OJ: Maybe you could give a concrete example of the beginning of the composing process?

ŠV: I can tell you how the beginning of my last piece of composition took place. We started discussing the opera libretto since 2014, and in the first months of 2015 it was already written and complete. Only then did I start thinking about the musical text and putting my thoughts inside. At the same time, however, there were many other things, so the process was slow. I think I started composing this opera in November 2015. It took several months to find information and talk to the director. Of course, the creative process is going to be faster by composing short works – say instrumental chamber music. I always work on a computer. I used to work on paper before, but now I get bogged down. When working with a computer, you simply do not need to overwrite it. Everything is much faster and easier.

Šimon Voseček. Photo © Nafez Rerhuf

OJ: How would you like your music to be presented and understood by the public? What would you like to represent your creations?

ŠV: It is important to me that the music touches my listeners emotionally. I perceive each piece as a story and believe that my music communicates this concept to the public. I think my work is experimental – I do not try to copy anything. The genre of the piece is very important to me. When writing texts or music, I always understand that a particular genre raises some expectations for my listeners. You can always go ahead with expectations and shock people by creating one or another original technique.

Suppose I write a comedy, although I try to simplify everything and convey all the images in an enhanced way, I always use modern, unpopular compositional techniques. I do not choose tonal music to express dramaturgy or emotion, although I do not believe that tonal music is dead today. Tonal music as a tool could be extremely useful and productive for the developer. Simply the problem is that no big composers choose to create it anymore, they try to compose something new. Humor is like a form of communication with the public. This is not always important for contemporary composers, but communicating with the audience is one of the essential creative processes for me.

OJ: You are both a theater actor and a creator of operas and music for musical theater. I imagine that drama and dramaturgy play an important role in your creation. How do you perceive this, and how does it manifest itself in you?

ŠV: Drama is everywhere, just everywhere around in my life. Most often, larger dramas are not on the stage, but behind the scenes. Well, my music is very theatrical. Like my life, I was a dancer from five and danced until I was thirteen. After that I became a music composer and theater actor. I spent most of my life on stage. It is a very physical experience, but it is difficult to name what influence it has on my work. You can communicate with the audience more by writing music to the theater or playing. Story and drama, direct forms of expression, have a greater impact on people than modern music techniques can achieve. I want to create a movie for the audience of opera or musical theater, with links to visual and sonoric, acoustic processes in our minds. As a result, the titles of my works do not have any particular intellectual or digital names.

Speaking of contemporary music, almost all of its listeners will hear this piece only once – on its premiere. Therefore, I do not see much sense in creating an extremely intelligent music that a man should fully understand the piece only after listening to it for five times. It is important that the philosophical idea of the work is understood by the performers, and I try to give the audience a different kind of impression. When I try to express a particular story in music, I try to imagine myself sitting in the audience.

OJ: How do you express the lyrics or the story by means of music?

ŠV: It is also important to link the text to the music so that they are simply not distinguishable. When writing an opera, the text is very important to me – rarely are good operas based on weak texts or poorly written librettos. Technically, music can support existing text or show what lies behind the text, make fun of the text, emphasize and highlight the drama that is written in the text.

Sometimes opera actors say something without believing their words. I can show it to the audience with the help of music. When I write music for a performance, I usually see a film in my head, and I often use my imagination. There is also a great deal of collaboration with the playwright and the director, especially for the duration of the music.

OJ: Have you ever acted in your own works?

ŠV: No, I have never taken part as an actor in my own performances or operas. In fact, drama is a great link between music and theater. I think, at least in Vienna, these two branches of art are extremely interconnected. I know many of my colleagues who work in both areas.

OJ: How often do you choose texts for your operas? Have you written any of the libretti yourself?

ŠV: When I wrote my first dramatic works, opera sketches, I talked about it with the theater playwright. He had already written a libretto and asked me to write music. I composed three musical sketches of the opera and changed almost all of the text he wrote without consulting him. I was twenty. [He laughs.] I just didn't think, but the playwright was, of course, quite upset, although the production was, finally, successful.

I always choose texts and stories according to their sound. The text must be musical, sound must be expressive. On the other hand, it must not be perfect or complete. In this case, the music should not supplement these words and there would be no need to build an opera.

OJ: You come from the Czech Republic. How does this affect your creation? Have you heard that one of the operas is based on the historical story of the Czech Republic?

ŠV: I think you're talking about the opera Biedermann and the Arsonists (2005-7). When I was composing this, I didn't even know I was writing a scene about Nazi crimes in the Czech Republic. In some countries, the opera is perceived as a criticism of communism and Nazism. Although, in truth, the concept of this work is much wider than these two approaches. This performance is against any dictatorship or fake news. The work is still not popular in the Czech Republic, which goes without saying. There are many people in this country who are unhappy with the story of blackmailing communism and highlighting crimes against humanity.

Johnny Herford, Adam Sullivan and Bradley Travis as the firemen in Šimon Voseček's Biedermann und die Brandstifter ('Biedermann and the Arsonists') based on the play by Max Frisch, in an English translation by David Pountney for Independent Opera at Sadlers Wells in London, UK. Photo © 2015 Robbie Jack

OJ: Have you ever compared yourself with the creative work of other Czech composers?

ŠV: From the musical side, some similarities between my works and those of Leoš Janáček are being noticed. However, I was never very concerned about the issue of nationality and the burden of being a Czech composer. There are many icons in the Czech Republic that you should adore as a composer in that country. But I can't, because they are simply not good enough.

The musical taste of people is too personal to be able to talk about nationality or patriotism. I believe that Prague is a sufficiently provincial culture. The Prague musical scene is very small and very concerned about itself. When I went to Austria, they stopped playing my music – I just stopped existing in their world.

OJ: How do you think you have changed in Austria?

ŠV: When I came to Austria, I changed a lot. I think I had a teenage attitude against experimental or contemporary music. I became much more open to different views, learned many new experimental techniques. Indeed, I have improved a lot.

Šimon Voseček. Photo © Igor Ripak

OJ: How would you describe the current music scene in Vienna?

ŠV: Here the musical scene is quite different. It is very large and much more related to the rest of the world. The municipality invests heavily in and funds for the city's musical life. Culture and especially classical music are still part of Vienna's city identity. Also, the musical scene in Vienna is very versatile and everyone can find the music that is close to him. On one hand, some composers are conservative and create string quartets, while others experiment with creating new sounds using electronics.

OJ: But are all the events affordable for the public at large?

ŠV: Cultural events are accessible to all. They are much more bourgeois than one could imagine. It is common for people from Vienna to attend contemporary music concerts and there is nothing elitist in it. I think that all this also encourages the interest of the inhabitants of this city in contemporary music.

Pupils in schools are also heavily trained in every musical style – from popular to classical or contemporary. My partner is a music teacher and he goes with children to the opera, concerts and theater performances. If you are a student and have no money, you can buy a standing ticket to the opera theater for three euros. At that time, when you become part of such an acoustic music, you can then look for further branches of music and open up many new possibilities – you can start listening to experimental popular music, club music or contemporary classical music.

OJ: Are there any advantages specific to German-speaking countries?

ŠV: I think that another advantage in German-speaking countries is that there is no clear distinction between the dominant metropolis and the province. Culture is also high in the smallest villages. What one is currently trying to do is simply to maintain the existing level – which is very high. I'm traveling a lot and I can boldly compare Vienna with Paris or London. The situation at the Vienna Opera (Staatsoper Wien) should probably be improved, as they rehearse before the premier, which is at a very high level, but when the performance or opera is already part of the repertoire, they stop rehearsing. And this is very much heard by the public.

Indeed, Vienna as a city has a number of complexes, as it is not a real metropolis like other cities – Berlin, London or Paris. Although the cultural level in these cities is indeed good, there is little to do with it. The advantage of this situation is that cities such as Vienna are constantly exploring and learning from other metropolises and therefore the city is developing together with them. And while living in a huge city, there is no need to look around in other parts of the country, because all the best things are in the capital town. This prevents broad development in the country. And at that time, one can boast of an extremely broad cultural view and tolerance towards other cities and their traditions.

OJ: Thank you very much for the conversation!

Vienna, Austria