SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterfully Controlled - James Brawn's Beethoven Odyssey impresses Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterfully Controlled - James Brawn's Beethoven Odyssey impresses Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

INTERPRETATION AND APORIAS

RICHARD MESZTO considers

Michael Kieran Harvey's

recent doctoral dissertation

Many years ago, in the classroom of a mid-level midwestern university, I stumbled upon a treasure trove of books - in this case identically bound texts, but all in a closet beneath a chalkboard. I discovered that they were graduate level dissertations from that university - many decades old. They laid there, seemingly forgotten, and as I browsed through the titles and texts, I became more and more sure that this functional obscurity was a waste. Each book represented enormous intellectual, psychic, spiritual and emotional energy. Such efforts cannot be wasted. Our world is in massive disarray on all counts. We can not let knowledge be forgotten just because of its format: we need all hands on deck.

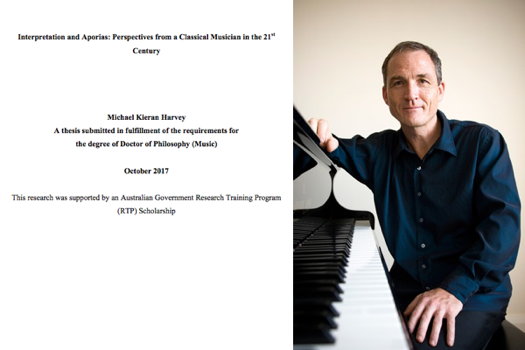

And so, I offer here an unusual essay: a consideration of the recent doctoral dissertation by the great Australian pianist and composer Michael Kieran Harvey. Certainly well-known to classical music listeners - and especially those with a penchant for modern classical music - Harvey received his degree in 2018.

Michael Kieran Harvey and the title page of his October 2017 doctoral thesis

This is not your average thesis. It is a highly personal review of the current situation for one pianist and composer - Harvey, and yet also for all pianists and composers - in all genres, let it be said. It starts with the experience of an Australian artist, but which applies around the world. The thesis challenges ideas of interpretation, repertoire and repertoire selection, the role of government subsidies for the arts, the effect of a giant and onerous tradition upon the modern artist, the limitations of interpretation created by teaching methods, competitions, the media and the musical management profession, and the struggle of the individual artist to find a place in this rather chaotic modern world and to find processes through the morass for his own creativity.

This may seem like an overloaded menu of issues to address in an academic thesis - and certainly highly charged ones in an environment of cool intellectual objectivity, but Harvey keeps the focus upon a few very significant ideas that are like a multiple Ariadne's thread.

First, is the concept of aporia. It is a logical conundrum that freezes all action, thought and hope. But, it is not just intellectual. It is also deeply existential.

Next is the hermeneutic circle: the process by which interpretation of a text (or a situation, I also think) takes place. Consider it a feedback loop of intellection.

The related concepts of appropriation and self-appropriation are next: the use, reuse, and reconfiguration of earlier ideas - either borrowed from other artists, cultures or thinkers, or from oneself.

With these concepts in hand, Harvey proceeds to find his own way as a composer and performer.

But, as can be expected for an academic work, there is the requisite 'Literature Review'. This is both the most dangerous portion and perhaps the most tedious for the same reason: it is very easy to fall into faddism of literature to review and follow too closely the latest and most current of cults - whether the cult is valuable or not. In the 1950s who read Renan, Strauss and Schweitzer when discussing Jesus? In the 1850s who cared about the nature of Beethoven's piano? (Hipkins, for one, Liszt - who bought it - for another. It now resides in Budapest.) Each era discards its immediate predecessors. These days even the post modernists are being discarded by the post-post modernists - modernist cubed? But, these intellectual fashions aside, these quoted authors often do have something to say of relevance, something which can be teased out of the jargon, the typecast verbal circumlocutions and the intellectual effrontery that the postmodernists-cubed often labour under as they sought to tear down what was old, in order to make a place for themselves. Yes, one must face quoted sentences that are defiantly antagonistic of comprehension. Ah, well. More important here is that this material is valuable for Harvey as he sets up his argument. Ignore at your peril.

Harvey turns to the great Franz Liszt and one of his most problematic compositions as:

... the purpose of this chapter is to highlight the changes that have happened to the virtuoso pianist composer from the 19th century and now. The chapter discusses Liszt's many approaches to interpretation in which he revitalized his musical output through the constant use of appropriating earlier material. (page 59)

Liszt's avocation (and business) is very aptly described by Harvey:

The music Liszt played served an important social function. It represented the ideals and beliefs of his middle to upper class audiences. He was a mythical evocation of what his audiences expected of him. Gymnast, magician, virtuoso, curator, priest and advocate, Liszt was all of these in one, and his audiences expected, even demanded that he lead them to new and unfamiliar territory to astound and excite them. (page 59)

This is crucial to understand what the ideal pianist was and must be. The idea of touring alone is omitted, while that is also important. Artists as diverse as Gottschalk, Paderewski, Friedheim (who experienced a riotous and symbolic series of events in Mexico), and later even Van Cliburn (who travelled to distant enemy lands and slew the dragon of godless Communism at its own doorstep - earning a ticker-tape parade upon his return to America), all of these artists aspired to Franz Liszt's world-striding conquests. Napoleonic war without the bloodshed - for, the battle-field was the piano's keyboard.

But, Liszt also represents on a smaller scale, issues of coming to terms with his own musical material. What is the fodder of the great pianist's achievement? It can only be musical compositions - for without those, the pianist is mute. (Would that modern pianists remembered that as they consistently maltreat their contemporaneous composer colleagues).

So, the composer as pianist must create something for his solo recital ammunition. Harvey takes up Liszt's Études d'Exécution Transcendante, which exist in three versions, the middle being the most demanding, elaborate and extreme (though I've always felt that Feux Follets of the 1837 version is better and indeed easier to play).

Harvey very rightly points out that Liszt promised twenty-four etudes, but never produced more than twelve in this series.

The lack of completion could indicate a form of creative aporia in Liszt. (page 60)

But, one of the etudes concerned Liszt even more than the others: Mazeppa. Drawing on his own 1826 ‘Burgmüller' type etude (page 62), Liszt added a grand tune and attached it (how indeed did he do so?) to the epic tale of a Ukrainian caught out in an affair and strapped to a wild horse to let run out of control across the steppe by the girl's enraged father. Mazeppa does not die, recovers, musters the Cossacks and returns for his fair beauty. Byron and Hugo took up the tale, and while Liszt attached Hugo's words to the text, he certainly knew Byron's version. How this harmless study of interlacing thirds came to be this mighty, if unplayable work, is one for the psychologists to ponder. (Czerny, who probably mentored the early version must have been dumbfounded by the transformation. I doubt he could play it and I shudder at the prospect).

But Harvey, more than a pianist, asks the important questions about Liszt's use of this work as an orchestral composition.

Liszt's orchestral tone-poem Mazeppa, written in 1851, is further indication of his endless need to repurpose, recontextualise and reinterpret. (page 64)

And most importantly (after a consideration of the reworking of the texture), Harvey notes:

Even the metaphorical imagery of the music has changed with this particular re- appropriation of Liszt's initial material. (page 65)

And from this analysis Harvey makes the important conclusion that Liszt:

... updated this material according to the changes he himself was experiencing as a musician, especially his role as a visionary thinker of the artistic avant-garde. This coincided with a period of intense technological and social change in Europe in the first half of the 19th Century. (page 66)

This trajectory of pianist, composition composer and format is vital not only to Liszt, but to anyone who wishes to avoid musical and mental stagnation. The poet Charles Bukowski sagely advises:

invent yourself and then reinvent yourself,

don't swim in the same slough.

invent yourself and then reinvent yourself and

stay out of the clutches of mediocrity.

- The Pleasures of the Damned; quoted at:

steemit.com/life/@walden/it-is-your-life-a-charles-bukowski-poem

Aside: I would point out - Harvey does not - that Mazeppa is a troubled work. Even the greatest pianists (such as Egon Petri) are stymied by it. Liszt also produced a version for piano four hands, and even for two pianos, if I recall, along with the version for orchestra. He could never quite get it right. It was required that Wagner, who understood the problem, perhaps having heard Liszt play it many times - and differently each time, and who probably talked with Liszt about it, threw his own lance into the future and solved the problem of Mazeppa in The Ride of the Valkyries, which is just Mazeppa corrected.

From his analysis of Liszt, Harvey writes personally (and ‘lamentoso'):

Although I don't play his music much any more, the idea of Liszt as a composer/performer and all-round musician still dominates my outlook on music, and even life. I wonder constantly what he would be doing if he was alive now, and wonder more specifically (and self-centeredly) what he'd be doing in my shoes, what advice he might bestow on a musician based in such a remote country as Australia - remote from his milieu and times that is. Would he even be involved in music at all? (page 68)

Harvey's analysis is ideal, being insightful and profound, because he is both a pianist and composer himself. This chapter, especially, should be read by Lisztian's and non-Lisztians alike.

I once met a graduate student who told me he was going to try to write his Master's thesis without ever using the word 'hermeneutic'. A brave and implausible goal. But, what is hermeneutics?

Hermeneutics as the methodology of interpretation is concerned with problems that arise when dealing with meaningful human actions and the products of such actions, most importantly texts. As a methodological discipline, it offers a toolbox for efficiently treating problems of the interpretation of human actions, texts and other meaningful material. - C Mantzavinos, plato.stanford.edu/entries/hermeneutics/, published 22 June 2016, accessed 22 March 2019.

Thankfully, Wikipedia gives a clearer definition:

Hermeneutics is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts.

Now, why would a composer and pianist be interested in this word and the concepts it conveys? Harvey comments:

The hermeneutic circle is the feedback loop of interpretation and reinterpretation that occurs with all musical works. It has elements of recursion too, as the circle, though infinite, is also constraining. (page 71)

Having wrestled with Harvey's chapter, what I believe he is aiming at is that every musical decision results in a cascade of further decisions and requirements for decisions, all of which ultimately loop back to the very first choice. Some of the decisions are conscious - 'Which piano shall I use?' - others are sub-conscious:

'Shall I try to play this as Horowitz does - no, I mustn't because he's an old school romantic pianist.' Indeed, some decisions are not allowed: 'I will use an 1850 Broadwood to play the Liszt Sonata.' Other choices are not even conceivable: 'I will play using the non-simultaneous hands method of Paderewski.' But, whatever choices the performer makes, it is sure to have repercussions. I give my own imaginary list:

'Oh, you play obscure, forgotten repertoire! Can't you just play something by Rachmaninov instead?'

'Oh, you play that frightful modern stuff. I can't stomach it. Can you play Chopin instead? Maybe on a fortepiano?'

'Why do you play music from your own country? I like Brahms - and there's a grant available to record his two piano concerti with the Kerguelen Avian Symphonic Ensemble.'

'Modern Music? Nonsense. Give us Purcell! (But, with the right ornaments!!!)

'Your own music? There hasn't been a good pianist turned composer since Liszt - and he wasn't that good.'

Harvey's reply is very clear:

Composition is a natural extension of the process of interpretation that forms part of the tradition of the classical concert pianist. The aporia that is generated by the interpretive process is a result of the contradictions inherent between notation and the expectations of the classical music tradition, which discourage freedom of interpretation in favour of received information. (page 70)

And:

My compositions derive their inspiration from the effort to capture a feeling of spontaneous improvisation. (page 70)

But then, what if the performer chooses to be, like Liszt, a composer and perform his/her own works? Where does that fit in? The same applies for a pianist who plays modern - ie modernist and recent - music.

Harvey writes:

Hermeneutics is traditionally the study and interpretation of ancient texts. This is a never- ending cycle of interpretation and re-interpretation .... Similarly, the technique of self- appropriation that I am investigating in my own compositional style – the technique of reinterpreting self-generated material in a constantly morphing series of recursions – means that the process of self-appropriation is never-ending in all parameters. (page 73)

And here is a very serious problem. Let us agree for the moment, that hermeneutics is 'traditionally study of ancient texts' and indeed, often religious texts. The sacredness of the texts is crucial. Often they are considered written by God - The Bible, or the Koran. Other times by inspired teachers - Zoroaster. In other cases by inspired savants - Heraclitus, subjected to analysis by Heidegger, or the Chaldean Oracles, subjected to analysis from Proclus to Plethon. But, these sorts of texts, and these most especially must be considered different from the texts produced by mere mortals. I concur fully in the Rabbis studying their sacred books and using every mental device possible to seek and to find deeper and deeper meanings. They will find them. However, I do draw the line on materials that are not written by God, or even demigods. Perhaps one failing of the modern critics is that they have taken techniques and attitudes appropriate to the analysis of sacred texts and applied them in areas where the techniques do not apply: the working results of mere humans.

Appropriation is also a very current, popular and fancy term. I firmly believe that the term means something and that there are really ‘appropriations'. The word, though, is used to describe outright theft in anything from culture (always another's culture), to artifacts, to quotation, to misuse of quotation, to personal reuse of material and more. Prokofiev's Sonata No 4 which is described as ‘from old notebooks' might be considered (self-)appropriation. The Elgin marbles are another form of appropriation. Sampling is another, as is just the standard method of academic quotation. I suppose operatic fantasies are appropriation and even the taking up of a folk tune for a set of variations is appropriation. In a way, it is the ultimate complaint of the cult of originality: if any idea can be found to have been created elsewhere, then it is a case of appropriation - and not creativity.

You can probably tell that I am a little dismayed at this term, appropriation. I think it is bandied about in a general way when more specific terms are better. For instance, I am a little concerned about an indigenous claim of its art form being appropriated by an artist as unacceptable when the indigenous population communicate their outrage on a phone designed in Southern California. I dislike complaints of a restaurant trying out a new menu with items from a distant land being appropriating when the complaints are made by people wearing jeans manufactured in another distant land (probably by underpaid staff). I do not wish to offend, but, I rather think that people are becoming offended too quickly. We need more precise terms to describe these situations - and take issue with them - rather then just the term appropriation which is being applied to far too many matters indiscriminately.

Chapter 6, My Hermeneutic Circle and Strategies for Composition, is by far the most important, densest and most difficult section for which to provide an overview. I shudder at the prospect, in part because, taken out of context, some of the discussion can seem far too abstruse. But, the issues are serious, and the tools of intellect are at hand, so why should one not delve deep into the subject?

Harvey draws together the following ideas for his advance from aporia: Recursion, Coalescence, Discontinuity, Proportionality (Ratios and Sequences), Maximum variation within minimum parameters, Collaboration. Each of these strategies is provided a strong and detailed analysis and description of method for his compositional process.

To conclude (and massive conclusion it is) are three chapters entitled 'Proof of Concept'. Thus, having set up the nature of the problem, the process of his solution, Harvey offers his own compositions as verification of his success and achievement. The two major works discussed are Patañjali and The Green Brain.

Patañjali is a dense, complex, massive and overwhelming multi-media work that combines Eastern thought and Yogic method with almost indescribably complex compositional processes set for an ensemble of musicians who are called upon to exhibit the most extreme powers of virtuosity.

The Green Brain takes up Harvey's scientific interests and draws on - appropriation! - the data of science - in this case, insects, for matter to create the compositional material. Harvey writes:

I use such schemata in my own works to generate new connections and ideas, for example in the cycle The Green Brain, where the idea of the constantly evolving morphology of the arthropod is also able to generate vastly different kinds of musical approaches to form, harmony, melody and rhythm. (page 92)

Booklet cover for Michael Kieran Harvey's 'The Green Brain Cycle'. © 2018 MOVE Records

Harvey's music (not just here, but in many of his works) is what I might say influenced by a rock term 'The Wall of Sound'. Now, that is not quite correct, as Phil Spector's invention of production mixing of recorded sounds for radio broadcast and playback on monophonic equipment (always monophonic) is slightly different. But, I'd like to appropriate the term - and redefine it for what I hear in Harvey's music. His music is massive, dense, sonically complex, rhythmically detailed, but timbrally purposefully restricted. Each section maintains a very specific sound quality (collection of timbres), as if one were passing by a loud sound source which retained its character for an extended period of time. In a simple way, imagine the sound of a jet airplane overhead - it remains itself, with one timbral character throughout its passage through our awareness. Or, imagine the sound of cars on freeways. Both are extremely simplified examples, but this may help get the point. Now, inside Harvey's sound are events, concoctions, transitions, melodies, rhythms, alterations, patterns, even specific data (like the number of some scientific parameter, or the Fibonacci series), but what we hear on the outside is the roaring - not necessarily a description of volume levels - of the inner pulsations. The trick for the listener is to find a way into the sound. Some might prefer to call this 'timbral music' or 'spectral music'.

My experience with Harvey's music is that repeated listenings are required where, in each listening, I focus upon one of the instruments and try to follow what it is doing until I hear its nature, at which point, I will also begin to hear the nature of its relationship with other instruments and timbres.

Harvey also discusses some of his other works in another chapter, and while some might be shorter in length, they are no less worthy of consideration and hearing.

After my wide traversal survey and rampaged flyover, can I say what conclusions Harvey reaches? Well, I rather fear that the world will continue to give him cause for aporia, and that the hermeneutic circle is in danger of becoming a wild ride that makes Mazeppa seem something fit for Disneyland. Harvey is a titanically powerful musician who is struggling in a very strange (and inhospitable) environment, to create something worthy of consideration and not merely something that will top the charts for a few weeks only to sink into oldie radio. The aim is high, the skills are great and we can strongly hope for his success.

Copyright © 28 May 2019

Richard Meszto,

Mazeppa, Alberta, Canada