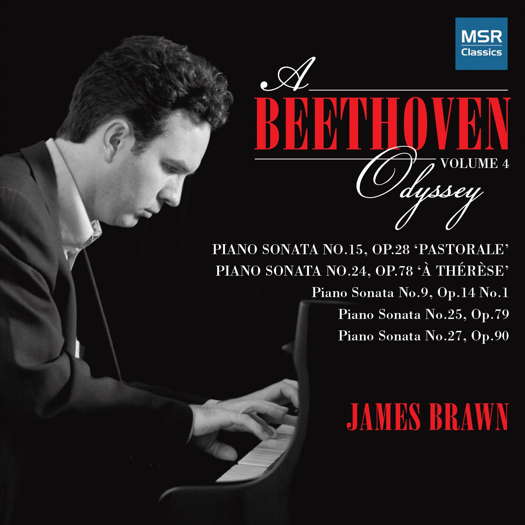

A Not so Merry Widow

Damiano Michieletto's joint venture with

La Fenice is not a success in Rome,

as described by GIUSEPPE PENNISI

On 14 April 2019, Teatro dell'Opera di Roma unveiled a new production of Die lustige Witwe (The Merry Widow) by Franz Lehár. This is a joint venture with Venice's La Fenice opera house, where it had its debut about a year ago and was highly acclaimed, especially for Damiano Michieletto's stage direction and his usual team - Paolo Fantin for sets, Carta Teti for costumes and Alessandro Carletti for lighting. Michieletto is one of the stars of Italian directors and I have often appreciated his work. The reception of this Die lustige Witwe in Rome was not so warm, and there were also some boos mixed with rather tame applause. Yet for a production in Rome last year of Berlioz's La Damnation de Faust, Michieletto was awarded the Premio Abbiati, Italy's main prize for classical music. I had rather mixed feelings about the staging.

Die lustige Witwe has sublime music; for this reason it has been one of the favorite scores of conductors such as Bernstein, Karajan, Kleiber, Matacic and many others, amongst the best batons of the twentieth century. The 'operetta' has also been much appreciated by singers such as Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Nicolai Gedda. Its waltzes and mazurkas demand the best étoiles and a very well trained corps de ballet. Its orchestral playing deserves top-notch musicians and even some well-rounded soloists.

It is a special operetta. It erupted when this type of musical theatre was considered on its way out. The seventies and the eighties of the nineteenth century had been the heyday of Viennese classical operetta, with Johann Strauss being the best-known and most popular composer. The exceptional success of this stylistic fashion produced a horde of librettists and composers who adapted the genre in a thousand of different ways; only a few of them propagated new ideas, melodies and rhythms. Thus, the genre was dying out when its leading exponents were still alive. At the turn of the century, little or no operetta seriously existed, and nobody believed in the possibility of its renaissance. A similar phenomenon had occurred in France where operetta was mostly linked to the name of Jacques Hoffenbach and to its sharp satire of the upper class in the Second Empire and in the Third Republic. Operetta was alive and well in Britain due to the excellent Gilbert & Sullivan trademark, but it was quite witty and too full of idioms to be appreciated across the British Channel, in continental Europe.

Die lustige Witwe was premièred in Vienna's An der Wien Theatre on 30 December 1905, only three weeks after Richard Strauss' Salome had shocked its Dresden audience and music critics worldwide. Albeit very different in many aspects, the two works have the same basic theme: sex, money and power as perceived by a woman. It is the same core element of Strindberg's plays as well as a signal of the beginning of Freudian psychoanalysis. Musically, Franz Lehár's waltzes and mazurkas were as revolutionary as Richard Strauss' dissonance. It is significant that The Merry Widow became world-famous not right after its première in Vienna, but a few months later as a result of its tremendous success in Berlin, where its fiery and unconventional spirit was at once recognized and acclaimed.

The text is amusing but not exceptionally brilliant. It is based on a rather dull French play, L'attaché d'ambassade by Henri Meilhac. The real marvel is the music: in a way, Lehár brought the Wagnerian revolution as close as possible to the dance hall and to the general entertainment theatre. There is a clear basic leitmotif, the love waltz around which other themes enfold, such as the brisk Maxim's march, Hanna's brilliant entrance aria, the melodious Vilja song, the tender pavilion duet, the chorus of the grisettes, and the Septet in the second Act, played and sung again at the end of the third Act. Lehár's waltzes are more caressing and sweeter than those of the classical Johann Strauss, and the orchestration is much richer.

Smart staging is required. In 2010, I reviewed a production where the action had been moved from 1905 to 29-30 October 1929, ie to the beginning of the major financial crisis, which opened the way to the Great Depression. In the background of a single set, where projections and props provided for the changes in scene - the Embassy of the bankrupt Balkan Kingdom, Hanna Glawari's fabulous mansion in Paris and finally Chez Maxim's - the audience saw stock exchange data and indexes like in a ticker of a financial TV program. Of course, the indexes fell until the final happy end, when a marriage and a lot of money saved everybody, and the stock exchange became bullish. The costumes were strictly in the 'roaring Twenties' style. The spoken parts were reduced to the essential - as in the original 1905 edition - by deleting the jokes gradually added during the last century and now considered part of the tradition.

Michieletto too updates the action. The plot evolves in the nineteen fifties and deals with the threat of bankruptcy of a commercial bank, rather than a small State in the Balkans. However, the staging does not seem to be in tune with a score that is, at the same time, sentimental, ironical, and full of melancholy for a bygone period. Also, it is quite odd to see disheveled youngsters dancing rock-and-roll on stage, while in the pit the orchestra is playing polkas and mazurkas, in addition to waltzes. Finally, Die lustige Witwe requires elegance: the 1950s attire should have had the signature of fashion maisons such as Chanel, Schubert or Gattinoni, rather than looking like the product of a Primark end-of-season sale. The best aspect of the production is the use of the original language, not one of several Italian translations.

A scene from Damiano Michieletto's staging of Franz Lehár's The Merry Widow at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2019 Yasuko Kageyama

The musical performance makes up for the rather scuffy, yet pretentious, staging. The conductor Costantin Trinks underlines the innovative aspects of the score - the central role of the love waltz and its connections with the other themes; the orchestra is quite good, especially the strings. Trinks has a lot of experience with Wagner; he gives the key waltz almost the role of a Wagnerian leitmotif in its interplay with the rest of the score.

A Wagnerian bass-baritone, Anthony Michaels-Moore, sets the tone in the well-known Septet Wie die Weiber ... Ja, das Studium der Weiber ist schwer, and drives the other six singers of this spicy concertato. Hanna Glawari, the widow everyone wants to marry for her money, is Nadja Mchantaf, with a good melodious voice but limited volume for the large Teatro dell'Opera; nonetheless, she received a well-deserved applause at the end of her entrance aria Bitte, meine Herr'n, and in the difficult second Act song, Es lebt' ein Vilja.

Nadja Mchantaf as Hanna Glawari, the title role of Lehár's The Merry Widow at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2019 Yasuko Kageyama

Of course, she does much better in the duets with Paulo Szot, an experienced baritone who is her Danilo Danilowitsch. Szot's well-rounded voice is apparent from his entry aria, Oh Vaterland, du machst bei Tag, to the final Lippen schweigen. However, he no longer has the attractive look he had when some fifteen years ago he was a Mozart star, especially at the Aix-en-Provence Festival.

Nadja Mchantaf as Hanna Glawari and Paulo Szot as Danilo in Lehár's The Merry Widow at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2019 Yasuko Kageyama

The second couple - Valencienne and De Rossillon, sung by soprano Adriana Ferfecka and lyric tenor Peter Sonn - is well balanced from the first duet, So comme Sie!

Peter Sonn as Rossillon and Adriana Ferfecka as Valencienne in Lehár's The Merry Widow at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2019 Yasuko Kageyama

The young singers from Teatro dell'Opera's Fabbrica training project, who perform several minor roles, were very good.

Copyright © 20 April 2019

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy