FEEDBACK: She said WHAT? Read what people think about our Classical Music Daily features, and have your say!

FEEDBACK: She said WHAT? Read what people think about our Classical Music Daily features, and have your say!

A FORGOTTEN COMPOSER IN ENGLAND

RICHARD MESZTO writes about

Hungarian-born Emanuel Moór

Hungarian-born Emanuel Moór

Emánuel Moór was born in Hungary in 1863. He made an expedition to America in the late 1880s, married an heiress, moved to England, where he lived for many years, then eventually decamped to Switzerland, where he died in 1931, aged sixty-eight.

Moór's music is almost utterly forgotten and his activity as an inventor is even less well known.

But, at one time he was championed as a composer by no less than Pablo Casals. That endorsement alone should be sufficient to at least ask these two questions: who was Emanuel Moór and, now that I've got your attention: what was he doing in England?

Moór was a pianist, composer and organist. He studied composition with Robert Volkmann - a little know composer who wrote Brahmsian music before Brahms. It may be that Moór studied, or met, or had a lesson with Franz Liszt. The connection with Liszt is mentioned in all Moór biographies, but Moór is not mentioned in the catalogue of Liszt students in Alan Walker's magisterial biography.

Moór was an extraordinary pianist and there is even a very early recording of him, online at the organization that owns the recording, the National Parks Service in the United States:

AUDIO: WANGEMANN'S 1889-1890 EUROPEAN RECORDINGS

While in America Moór met the young lady Anita Burke, who was the daughter of a very wealthy 'importer of malt liquors'. Marriage followed and a life of ease thanks to the generosity of Moór's father-in-law.

The young couple moved to England in about 1888 and had various residences in Surrey. Moór's works were performed in London - though not always to considerate or high praise.

Indeed, by the time Moór met Pablo Casals in 1905, Moór considered himself forgotten and ignored. Exactly when Moór and his wife left England is not clear - they wandered around Europe a great deal, but by 1907 at least, they had re-settled in Switzerland.

Casals championed Moór and performed Moór's works widely himself.

Many publications were through the French firm of Mathot and other publishers include Simrock and Schirmer. Many works, it seems, remain in manuscript.

As with so many composers, though, The Great War decimated Moór's compositional activity (he composed very rarely after the War), but his volcanic mind could hardly be quieted.

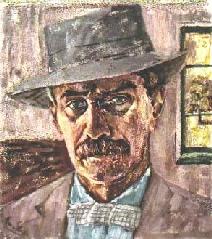

Emánuel Moór self-portrait

Instead he turned to painting and inventing. After producing a superb self portrait, and some patented inventions, Moór's mind returned to something he may have had suggested to him by Liszt, or perhaps from his own experience as organist: the idea of a multiple manual piano.

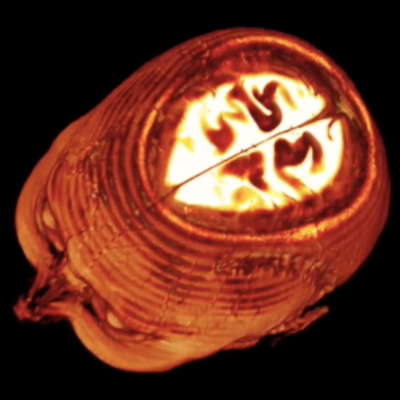

The last decade of his life was spent developing, building and perfecting a remarkable instrument that while having only one set of strings, has two keyboards angled towards each other which allows for playing by one hand on both. The result is a massive increase in the potentialities of the instrument. Donald Francis Tovey was an early and ardent supporter, Moór's second wife Winifred Christie-Moór was a fervent activist on its behalf. Later the pianist György Sándor (who played his New York debut on the instrument) taught its methods, while the pianist Gunnar Johansen recorded the complete works of Bach in the 1950s and used one of these instruments for a vast swath of the compositions.

Bosendorfer-Moór instrument in New York City, belonging to the Gunnar and Lorraine Johansen Charitable Trust. Photo © 2019 James P Colias. Used with permission.

Herbert Shead wrote a fine book on it (including detailed technical drawings and patent information). Later, Larry Sitsky composed a giant and powerful work for the instrument.

Book cover: The History of the Emanuel Moór Double Keyboard Piano. Herbert A Shead. From the personal library of the author of this article

But, it is not as an inventor that I am interested in Moór.

Rather, it is as a composer in England in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras.

Moór represents a forgotten voice of this era and in this place. His music was not much heard, but he was certainly known to his colleagues. (Indeed, he and the Polish pianist Paderewski - a London favourite to be sure - were apparently enemies.)

The questions that arise are these:

- Was Moór influenced by English composers?

- Did Moór influence English composers?

- Is there some similarity between these composers?

I would suggest the tentative answer is 'Yes' in all cases, but albeit in a roundabout way. The connection is Brahms.

Now, as mentioned above, Moór took his Brahms manner from Volkmann, a predecessor of Brahms. But, the music of Brahms was widely known in London during this era and was often paced as an antidote, or opposite, to the also considerable cult of Wagner.

Brahms was certainly a considerable stylistic influence upon major figures - either for the good or the bad. His techniques were widely considered and his music was added without question to the Classical repertoire.

Moór's music has many earmarks of Brahms (again, rather via Volkmann) and if heard, his music would appeal to anyone who admires or loved Brahms.

However, there are also moments when Moór's music treads very closely to English composers such as Elgar, Parry or Stanford, and more especially to Ralph Vaughan Williams, and sometimes even Gustav Holst. There are tunes, sonorities and forms that 'breathe the air' of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras (and please be clear that I certainly do not mean that this is all derived from Brahms).

This is actually a very important area for investigation: the character of Moór's music and its relation to late nineteenth century English composition.

I also believe that Moór's music would appeal to those who are a little tired of hearing the same 'twelve masterpieces', and seek something similar, but unfamiliar, by a gifted and professional composer.

If I may suggest an approach to Moór's music, I would consider him a combination of Brahms sound world, but tinged with the more quickly moving harmonic palette of Max Reger (who arranged one of Moór's compositions), though without that composer's density of involuted chromaticism.

Moór has a wonderful sense of sonority: in slow movements, there are points of the most aching and heart-wrenching beauty. His dramatic movements are a little more difficult, because his themes of this kind are quirky and not always clearly structured - they sometimes seem like improvisational ideas not firmly worked out. But, often in scherzo movements Moór hits the nail exactly on the head.

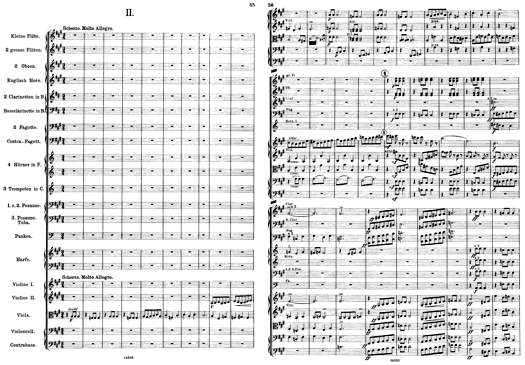

The first two pages of the second movement (Scherzo. Molto allegro) of Emánuel Moór's Symphony in E minor, Op 65, published in 1906 by C F W Siegel's Musicalienhandlung, Leipzig

Moór wrote symphonies, an enormous quantity of chamber music, operas, choral works, and concerti. There are many works for cello, and, though I have not seen the scores, numerous (?) works for harp, which should gladden the hearts of those instrumentalists greatly. Among his piano works are giant sonatas, gem-like miniatures, excellent transcriptions of Bach, and amazing beauties all around.

Was Moór an English composer? No. He was an immigrant. And we know that immigrants are not natives.

But, for a good ten years or more, he lived and worked in England, breathed its air, connected with its musical life, and both responded to that music and wrote music that may have influenced the sounds of others - maybe. Time will tell.

Winnifred, Alberta, Canada