Quite a Revelation

MIKE WHEELER attends the first concert of Nottingham's new orchestral season, with John Storgårds conducting the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra in music by Maurice Ravel, Camille Saint-Saëns and Igor Stravinsky

The new orchestral season at Nottingham's Royal Concert Hall began with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra occupying every available square metre of the stage for the 1911 version of Stravinsky's Petrushka. The 1947 revision for smaller orchestra is more frequently played, so this was a rare opportunity to hear the full-on original - Nottingham, UK, 1 October 2024.

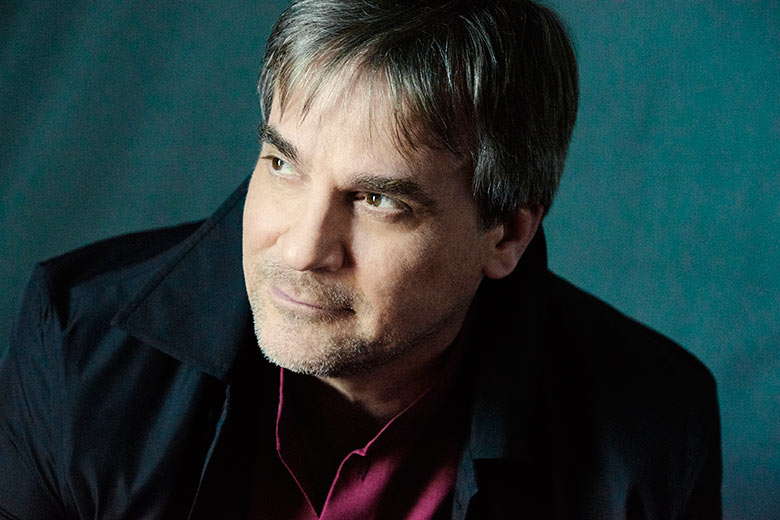

With its chief conductor John Storgårds, the BBCPO brought the action alive in so many details, from the buzzing crowd music to the wheezy street organ, mechanical and aloof.

John Storgårds. Photo © Marco Borggreve

The Showman's solo flute incantation - Alex Jakeman - was all sinuous mystery, and Petrushka, the Ballerina and the Moor performed a vigorous Russian Dance. In the scene of Petrushka alone in his cell, his famously bitonal clarinets sounded ghostly, and pianist Ian Buckle gave Petrushka himself a soulful voice. In the Moor's scene, drum and cymbals recalled so-called 'Turkish Music' from earlier centuries, as Stravinsky no doubt intended, the Moor's frustration - he was obviously having a bad day - came across clearly, and the Ballerina made her entry to Tom Fountain's bright, perky solo trumpet.

The fourth tableau had, once again, a vivid sense of crowd movement. The folk song 'Down Petersky Street' billowed out and, among the sequence of small vignettes, the lumbering performing bear, with Mike Lewis's tuba giving voice to the creature's agony, was pitiful to hear. Petrushka's death was a truly shocking moment, and its aftermath, with Petrushka's ghost thumbing his nose at the audience - which audience: on-stage or in the theatre? Stravinsky didn't say - felt genuinely uneasy.

Hearing the 1911 score was quite a revelation, not least in those moments that clearly rubbed off on The Rite of Spring and, when the Moor chased Petrushka out of his cell, Bartók's The Miraculous Mandarin, while leader Zoë Beyers' solo in the Russian Dance contained hints of The Soldier's Tale to come.

Zoë Beyers. Photo © Bill Leighton

Shorter works for soloist and orchestra are sometimes viewed as awkward to programme. Well, here's one possibility - programme two of them. Dutch violinist Simone Lamsma, replacing an indisposed Jennifer Pike, got Saint-Saëns' Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso off to a gentle, sotto voce start. The quick music was poised, buoyant and strutting, with rhythms that crackled and snapped, and Lamsma hit the solo part's every technical demand squarely in the middle.

Simone Lamsma. Photo © Otto van den Toorn

In the unaccompanied violin solo that begins Ravel's Tzigane, Lamsma held us spell-bound with her husky lower-string tone, in a performance full of fiery temperament. The orchestra's entry vividly evoked the sound of the dulcimer-like cimbalom, and throughout, earthiness and sophistication went hand-in-hand, with an appropriately frenzied ending. Afterwards, Lamsma graciously handed her bouquet to Zoë Beyers.

Saint-Saëns' Symphony No 3 is known as his 'Organ' Symphony, for understandable but not totally justifiable reasons, given that the instrument plays in only about half of it, and is not always in the foreground, even then. In a carefully-judged performance such as this, it can be overwhelming for all the right reasons. After the slow introduction roused expectations, the quick string music was all soft but tense rustling to begin with, while every now and then the woodwind emerged, cavorting in some walpurgis night celebration of their own. The stealthy move into the movement's slow second half saw organist Jonathan Scott setting down a softly purring foundation for the strings. The account of this section was deeply felt, in a way that seemed to hold the key to experiencing the symphony as more than just a sonic firework display. The first and second violins' smooth voicing in their Bachian two-part invention suggested a clear reason for placing them on opposite sides of the platform. They weren't on this occasion - a missed opportunity. There was a real sense of questing - of wondering where we were, almost - which gave real point to the ending's deep serenity.

The second movement's first half was marked by taut, incisive phrasing. The first trio section saw the piano duo team of Ian Buckle and Benjamin Powell scampering all over the texture, scattering glitter wherever they went. When the Trio returned, after the reprise of the movement's opening, conductor and players relished Saint-Saëns' misleading build-up, before the music scattered and faded.

There can't be many organists who don't savour the instrument's theatrical entry at the start of the finale, but Scott managed to be imposing without the sledge-hammer effect. The ensuing fugue showed determination, with tranquility in the brief pastoral moments. Thanks to the earlier emotional probing, the end kept bombast to a minimum, feeling more like a celebration than a bout of tub-thumping rhetoric, and was all the better for it.

Jonathan Scott

Scott's encore, the Toccata from Widor's Symphony No 5, kept the old warhorse fresh and buoyant.

Copyright © 8 October 2024

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK