- Pierre Fournier

- Wisconsin

- Wolfgang Gönnenwein

- Bernard van Dieren

- Robert Harbinson Bryans

- Andrew Arceci

- Van Cliburn Competition

- Maddy Aldis-Evans: Woven

LEARNING TO PLAY AGAIN

WITH 'THE NUTCRACKER'

JEFFREY NEIL shares some thoughts about Tchaikovsky's ballet, following a visit to Oakland Ballet's production in California, USA

In 1903, the year that Graham Lustig set his production of Tchaikovsky's The Nutcracker ballet, nothing particularly momentous happened in the political theater of adults. However, for a turn-of-the-century Fritz and Marie, as well as their Uncle Drosselmeyer, Christmas of 1903 would have been an occasion for new toys and technical wonders, following a century that saw the possibilities of toys ever expanding. The luckiest children woke up to a 'Teddy's Bear', a plushie inspired by the American president for refusing to shoot a tied-up bear. 1903 was also when Orville Wright captured imaginations with the first airplane flight.

The Nutcracker has almost nothing to do with Christ's birth, and everything to do with the human capacity to engineer wonders - whether through sublime music and choreography or extravagant stagecraft and cunning toys. The ballet captured the culture that had grown around the Christmas holiday during the nineteenth century, particularly the development of mechanical toys, like self-propelled trains that ran on tracks, music boxes with pirouetting ballerinas, and dancing realistic animals.

An image of one of the exhibits from Siegfried's Mechanical Music Museum in Rüdesheim am Rhein, Germany. Photo © Jeffrey Neil

Oakland Ballet's production this year sought to elicit a childlike wonder in Christmas toys and glitter. Director Graham Lustig and Oakland Symphony guest conductor Pamela Martin delighted at the Paramount Theater. Uninhibited audiences of girls dressed like fairies and princesses could barely contain their glee, and adults broke out into spontaneous applause often, even gasping out loud to some particularly soulful dancing or glittery choreography.

Oakland Ballet

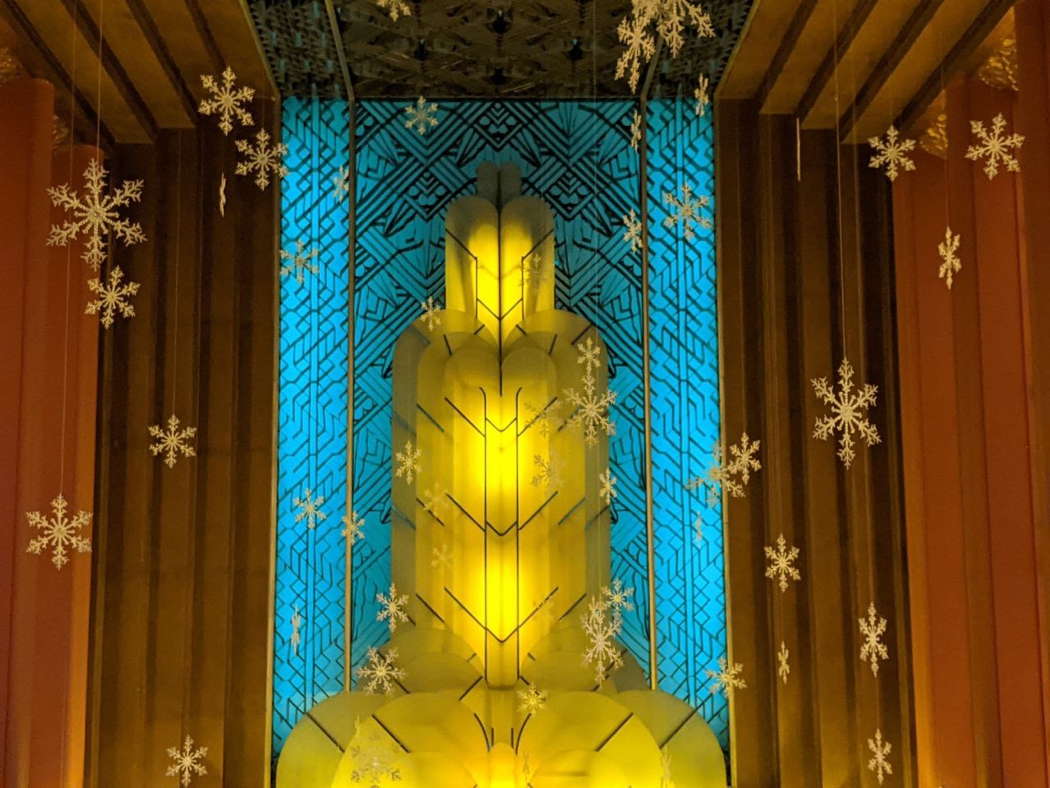

No less a subject of my review is the Paramount itself, an art deco jewel box inspired by the discovery of King Tut's tomb. E T A Hoffman, author of the original The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, no doubt would have approved of the Paramount to set his story.

The Paramount Theater in Oakland, California, USA. Photo © Library of Congress

Every production has to rediscover the kernel of the Nutckracker's story because the Krakatuk nut was plucked out when the director of the Imperial Theater in St Petersburg and the ballet's choreographer adapted the story and produced an anemic plot that disappointed Tchaikovsky. E T A Hoffmann's complex framed narrative - a literary shape that functions like a Matryoshka doll to contain one tale within another - has a rich and disturbing plot centered around the enigma of why the seven-headed Mouse King hates the Nutcracker, and who is the man that became the Nutcracker.

The tale is a pastiche of medieval genres with all the longing, real and metaphorical bloodshed, wounds, and courtship of the chivalric chansons. It has the lush physicality and eroticism of the thirteenth century Roman de la Rose; and it draws on a fixation with a luxurious Orient that is in the European imagination equal parts exquisite and grotesque, its people alternately eroticized and dehumanized.

Seen from a nineteenth century perspective, however, Hoffman's tale is also modern, depending on new technologies that make inanimate things seem to live in order to awe their owners. Marie's gift from Uncle Drosselmeyer, a dollhouse inhabited by a miniature animatronic version of herself and Fritz, is unsettling. It precipitates the coming-to-life of the Nutcracker, Fritz's infantry and cavalry, and the seven-headed Mouse King.

In the real world, there were such toys by the end of the eighteenth century. Designed to look like real people, the 'automaton' could perform feats that still amaze today, like a little boy writing a letter with a quill and ink or a life-sized woman playing the piano or the flute. These automata animate Hoffman's story and find their way into the ballet via the Nutcracker himself, who comes to life with a dance that is at first stiff and staccato; he is an automaton that dances to music. Through the course of the ballet, his increasingly fluent dancing to music is what proves there is life inside him. The ballet is full of human dancers that mimic automata: mouse soldiers, bonbons that jump, and in Lustig's production, prancing snowflakes. Let us not forget that Uncle Drosselmeyer is not just a judge, but a clockmaker. Pull back the clothes of the automaton, and its chest cavity and gut are filled with whirling cylinders, springs, and gears, engineered by clockmakers.

An automaton by eighteenth century

watchmaker Pierre Jaquet-Droz

By the year of Tchaikovsky's ballet, the technology of children's toys had matured further. There were self-playing pianos, mechanical violin sextets, music machines, carousels with music, and mechanical animals that appeared alive, banging on drums or stomping around.

Ludwig Hupfeld's 'Hupfeld Phonoliszt-Violina'

in Siegfried's Mechanical Music Museum

in Rüdesheim am Rhein, Germany.

Photo © Jeffrey Neil

The engineers aimed not simply to make machines that produced music, like a phonograph. They built a technology that made it appear as if a sentient being were playing the instruments that emitted the music.

When Tchaikovsky was composing The Nutcracker, toymakers had become masters of illusion. Marie's parents reproach her for swearing the toy soldiers had battled mice, and it is ironic since the goal of these toys was to blur the boundary between the living and the merely mechanical. The novel realism of the bisque porcelain doll meant it looked like it could converse at tea or skulk around at night. The delight and the terror of new technologies pervades Hoffman's original tale. Ideally, a production of the ballet will tap into this paradox: both the seduction and the taboo of blurring the line between living organisms and dumb matter.

Lustig's interpretation foregoes the danger for the delight. His addition of dancing snowflakes, little girls encased in balls of powder blue and white feathers, to accompany the snow maidens enhanced the playfulness of the flute and the elegant clarity of the clarinet and the harp. Metallic, sparkling snowflakes fall from the sky, and Lustig's innovation - the child ballerina snowflakes - tumble about in a sweet counterpoint to the elegant snow maidens. In that same scene, Marie and the Nutcracker arrive in a hot air balloon that looks like an upside-down Christmas ornament, a nod perhaps to the wonder of this early flying technology.

Behind the balloon, the set looks like a page out of a children's story. There is no attempt at verisimilitude in the backdrop; it reads like an illustration on a page. The danger and depth that can exist in children's playing, however, are absent: the lovely scenes are filled with light, the shimmer of organza and tulle. Nutcracker and Marie sit in a half-eaten cupcake, and the production is a parade of the adorable, like the pastry chefs with elongated hats and bristle-like fuschia hair.

But where is the dark magic? In the San Francisco Ballet's 2007 production, for example, the first scene features Uncle Drosselmeyer selling his clocks and toys in a dark alley. Later, in his cape and eye patch, Drosselmeyer turns the Stahlbaum salon into a kind of theater where he shows off the toys springing out of boxes. In Lustig's pleasant 'Christmas Eve Party', Drosselmeyer is not hawking his wares at night, nor is he, as in the Russian State Ballet's 2014 production, a nimble, Loki type in a glass wig and black satin: rather, he is domesticized and professorial in tweed.

The typical polarities in the ballet between meringue and bitter chocolate, joy and terror, the frothy and the uncanny are rooted deep in the original text which came out of Central and Eastern European Christmas traditions. The alpine devil Krampus and the black bearded Knecht Ruprecht of Germany terrified children, while the Russian Father Frost was more likely to demand ransom gifts in return for kids he had kidnapped than to deliver toys.

The automata, dancing confections, and spirited dolls of Hoffman's Nutcracker rarely offer unadulterated pleasure. In the Land of Sweets, the Nutcracker entreats Marie, 'I humbly beg your pardon ... that the ballet should have ended so wretchedly. But you see, these performers are all members of our mechanical ballet, so they can only do the same thing over and over again.' Balancing the delight of the dreamscapes is a sense of mechanical repetitiveness, even a suggestion of the danger of having one's imagination enslaved to fascinating technologies.

Much had already been strained out of Alexandre Dumas' adaptation of Hoffman's story, and certainly of the schematic plot Tchaikovsky was constrained to use. Artistic director Maurice Sendak has described the ballet, compared to the original text, as 'smoothed out, bland, and utterly devoid not only of difficulties, but of the weird, dark qualities that make it something of a masterpiece'. Sendak and Kent Stowell's 1980s production addressed this perceived lack by adding a short scene in the middle that communicated missing parts from Hoffman's story. They also omitted the long Land of Sweets setting (not the music) of the second act. Instead, they chose to 'face the inner logic of our script and march bravely where it led us', which was a seraglio. This is the kind of intervention that on the face of it comes off less as interpretation and more as hijacking a work, like setting Tristan und Isolde in Amsterdam's Red Light District, trading in sublime eroticism for raunch.

In this case, I think Sendak and Stowell were spot on, both in highlighting the erotic and in choosing an Orientalist fantasy setting. In Sendak's illustrated book, the seven-headed Mouse King also appears in Ottoman costume with scimitar, ballooning Turkish trousers, and moccasins with the upturned toe. The Mouse King plays the Oriental antagonist - the Turk, the Moor, or the Mongol - who is also the perfect foil and adversary. Later in the story, the Orient - the colonialist fantasy that Europeans constructed around Islam, Middle Asia, and the Far East, as theorized by the renowned scholar Edward Said - features repeatedly. It is a space of luxury, countless slaves and beasts of burden, and bottomless mysteries and resources - all of which can be seized and turned into toys for Westerners. Indeed, Uncle Drosselmeyer and the court astronomer wander for fifteen years and, finding nothing in an Asian wilderness, decide to return to Nuremberg to continue searching for the magical Krakatuk nut, the only thing that can return the princess to her lily white and rose red beauty. When they go back home, they find the magical nut, and it is covered with Chinese characters that spell out the word 'Krakatuk'.

But The Nutcracker is a winter's tale, ostensibly focused on the northern part of Europe; and moreover it is a confectionery story, so not surprisingly, there is a lot of white. Marie is mortified that the mouse wants to eat the sugar shepherds and shepherdesses, the flock of 'milk-white sheep', and indeed, the description of 'milk white' and red or rose are used to express much of what is beautiful in Marie's world. The Nutcracker is also 'white and red like milk and blood'.

So, too, is Lustig's Nutcracker with his large white face and red cheeks, a vermilion jacket and snow-white, satin leggings. This is a tale that is written as a narrative of European identity and its repeated equation of beauty with an idealized white complexion and red cheeks and lips. But it's also a story of the seductive power of Orientalist motifs to disrupt and entrance Marie and the Nutcracker. The Turkish music that plays in Candy Meadow is so beautiful Marie loses sense of the candied wonders around her. Then, 'twelve little Moors', who row Marie and Nutcracker, 'stamped their feet in a strange rhythm and sang', momentarily dispelling the trance state.

Nutcracker responds annoyed: 'Those Moors are all very well. But if they keep that up they're going to make the whole lake rebellious'. And that is what happens: 'a deafening hubbub broke out - a medley of strange voices that seemed to be partly in the air and partly in the water ...' The Orientalist fantasy stirs things up and unleashes uncontrollable music. It's dangerous and subversive, but Marie ignores it. She 'paid no attention to them' because she was gazing at her own reflection smiling back at her.

Lustig's ensemble breaks this self-reflective European gaze; it is as diverse as the City of Oakland itself. The shift from the way I have always seen this ballet cast to one that has Asian, Black, European, Latino, and Middle Eastern faces is enough to make me aware for the first time just how 'European' the story has been framed - even though it really isn't. Tchaikovsky's music is full of the sounds of Russia, straddling East and West, but productions often disregard this and perpetuate the world of 'white and red'. The troops are normally stultifyingly homogenous - and from what some of the Oakland Ballet's dancers have written, oppressively heteronormative. Not here. When Lawrence Chen takes off his Nutcracker mask, this simple action, done countless times since 1892, casts off a historical spell as well.

The ballet's ethnic dances, translated into edible commodities - coffee (Arabian), chocolate (Spanish), candy cane (Russian), marzipan (Danish and French) - are generally some of the most beautiful dances. In Lustig's production, the standout performances were Spanish chocolate and Arabian coffee. Here, the orchestra overcame the limitations of being miked and the lackluster acoustics of the Paramount. In the soft, slow dialog between woodwinds and strings of the Arabian dance, the music wafted like a plume of incense smoke.

Ashley Thopiah and William Fowler danced an extraordinary sensual duet. They mixed modern dance with ballet - or, at least, modernized ballet with cobra-like movements and a continual process of enfolding. The bassoon calls out into the night, and the lonely lover orbits over. The Arabian dance is one of distancing and rapprochement, the strings pushing away and toward winds and brass. Thopiah and Fowler conveyed the alternatingly timid and bold approach of the lovers - the clarinet, the oboe, and the bassoon calling out plaintively to the more confident violin and viola. It was a transcendent moment I would have repeated over and over.

Amber, myrrh and Oud wood, brass chandeliers, darkness, and hieroglyphs on cracked earthenware are conjured in the music. This is the most overtly erotic moment in the ballet, and one of the few that suggest a living world in distant lands - not just luxurious baubles or automata. Here is the 'strange rhythm' and here are the 'strange voices', of the twelve Moorish feet that annoyed Nutcracker, and the beautiful Turkish music, which charmed Marie. It's also the moment in Lustig's production that brought me closest to the eroticism, the longing, and the taboo of Tchaikovsky's music.

This takes us to the art of the Paramount Theater itself, which evokes the luxurious interior of a royal Egyptian tomb. Architect Timothy Plueger was inspired by the discovery of King Tut's tomb in 1922. The atrium and theater walls are covered with stylized women, some in Egyptian composite pose, their breasts and legs bared.

Detail showing part of the Paramount Theater's luxury interior. Photo © Jeffrey Neil

There are panels of sun-colored light with stylized reeds, and if you arch your head a teal strip of light, as if we were looking up from the bottom of the Nile. In the metal grating above are watery swirls and lotus shapes. There are animals or flowers and naked flesh throughout the theater, and where these are absent, the eye moves over intricate geometrical shapes.

Detail showing part of the Paramount Theater's luxury interior. Photo © Jeffrey Neil

If you bob your head and look closely, you can make out tiny little men working on the metal grate of the ceiling. Truly.

There is wonder in the drama enacted all over The Paramount, and I can't help but see this theater as perhaps the most apropos set for the story. In the Greek and Egyptian motifs, the theater as tomb, the tomb as jewel box, the jewel box as the Nile river, and so on ... we have that endless play of sensual fantasy, moving from one scent and scene to the next. We have Europe, Africa, and Asia - fantasies of the Orient and the Occident. Here, too, engineer and toymaker, blacksmith and clockmaker, artist and dancer, instrumentalist and singer, are endlessly playing.

Members of the cast for Oakland Ballet's 2023 production of 'The Nutcracker'

Perhaps this is the real gift of The Nutcracker, that it renews our capacity to play.

Copyright © 27 December 2023

Jeffrey Neil,

California, USA