SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fascinating Recording - John Joubert's string quartets, heard by Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fascinating Recording - John Joubert's string quartets, heard by Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

- Friedrich Klose

- Frederic Mompou Dencausse

- Stone Records

- Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos

- Bermuda

- Royal Festival Hall

- Schindler's List

- Salieri: Veneziana

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Melting Rhapsody - Malcolm Miller enjoys Jack Liebeck and Danny Driver's 'Hebrew Melody' recital, plus a recital by David Aaron Carpenter.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Melting Rhapsody - Malcolm Miller enjoys Jack Liebeck and Danny Driver's 'Hebrew Melody' recital, plus a recital by David Aaron Carpenter.

All sponsored features >>

THE POLITICAL SYMPHONY

JEFFREY NEIL asks some searching questions about classical music and protest

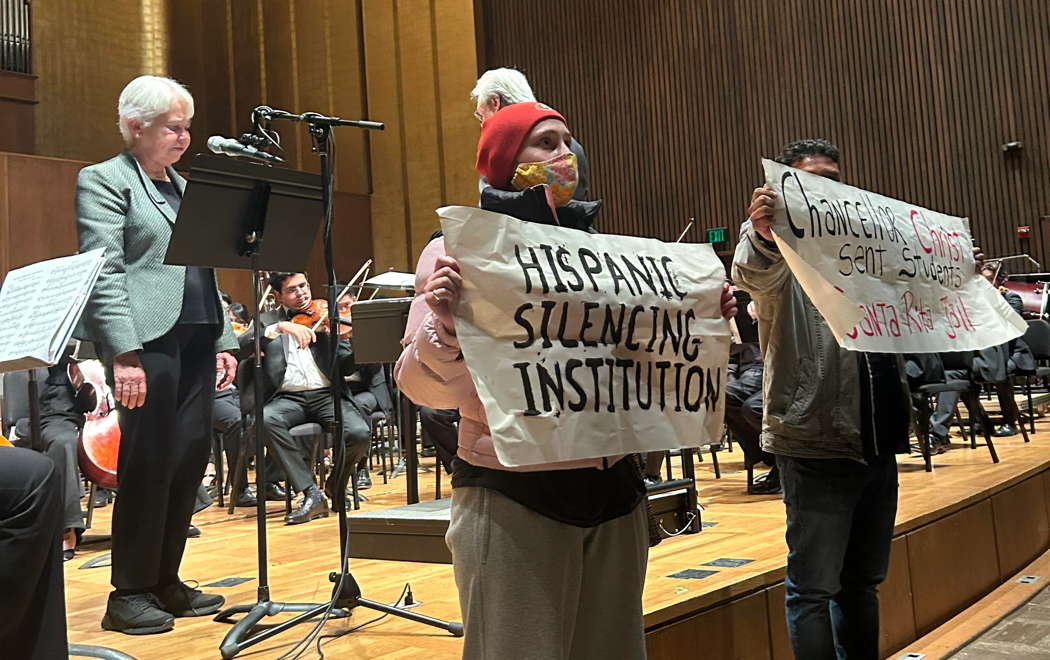

'Oboes have a gentle, plaintive quality, but they can be penetrating enough when the composer asks them to be', Chancellor Christ, the head of the University of California's Berkeley campus, declaims in a warm, playful voice at the 3 November 2023 performance of the UC Berkeley Symphony Orchestra. Before the stage stands a group of students silently holding up battered-looking posters declaring, 'Chancellor Christ sent students to Santa Rita Jail' and 'Hispanic Silencing Institution'.

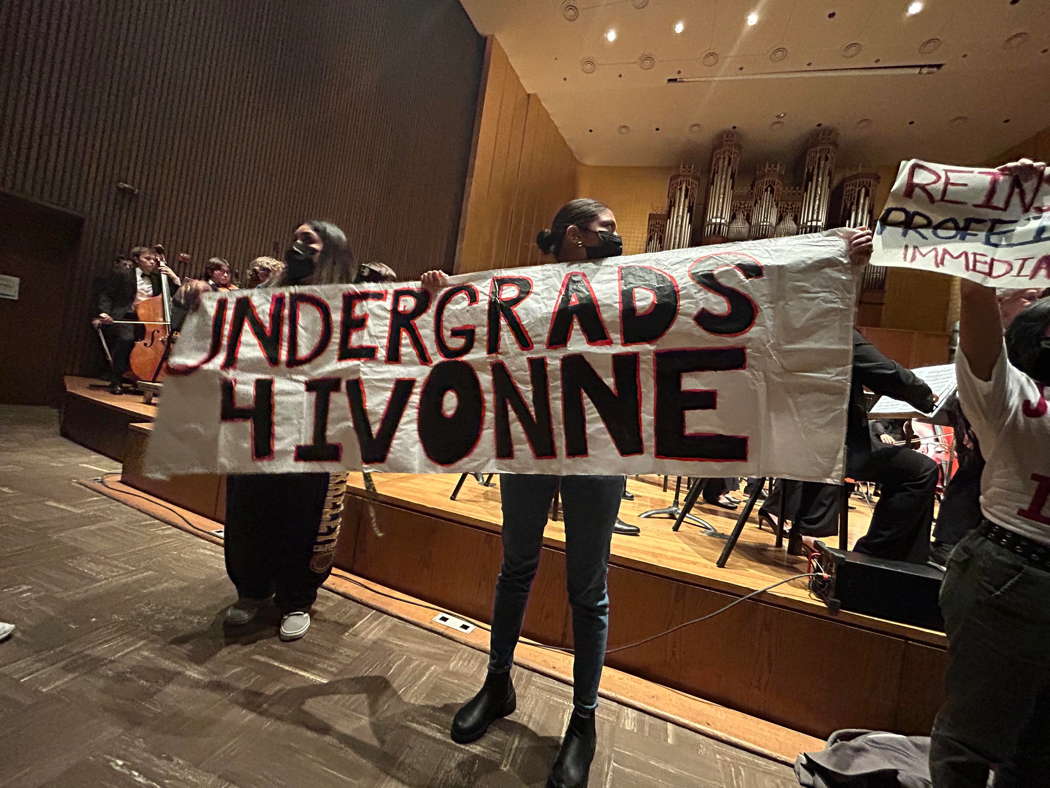

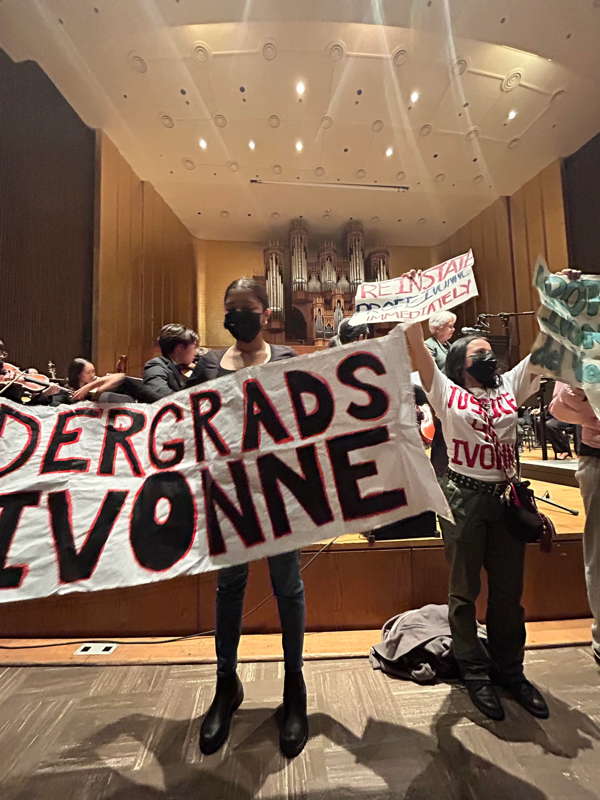

The protest at the UCB Symphony Orchestra concert on 3 November 2023 with, behind, Carol Christ and the UC Berkeley Symphony Orchestra

The protest threatens to occlude not just the oboe, but the coherence of the entire performance - or at least the attention of the audience. There's no small irony here: on the stage, the chancellor in the expected role of pedagogue, elucidating the personality and role of each section of the orchestra for Benjamin Britten's Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra; in front of the stage, students attempting to 'penetrate' the guard of the academic magisterium, and unlike the oboe, regardless of what 'the composer asks them to be'.

The symphony plays on. 'When I first saw them, I lost focus', admits Andrew Shin, a violinist in the UC Berkeley Symphony Orchestra. The protesters yelled briefly at one point, and he recalls the musicians responded with vigor: 'When they started to yell, we got louder and canceled their voices out'.

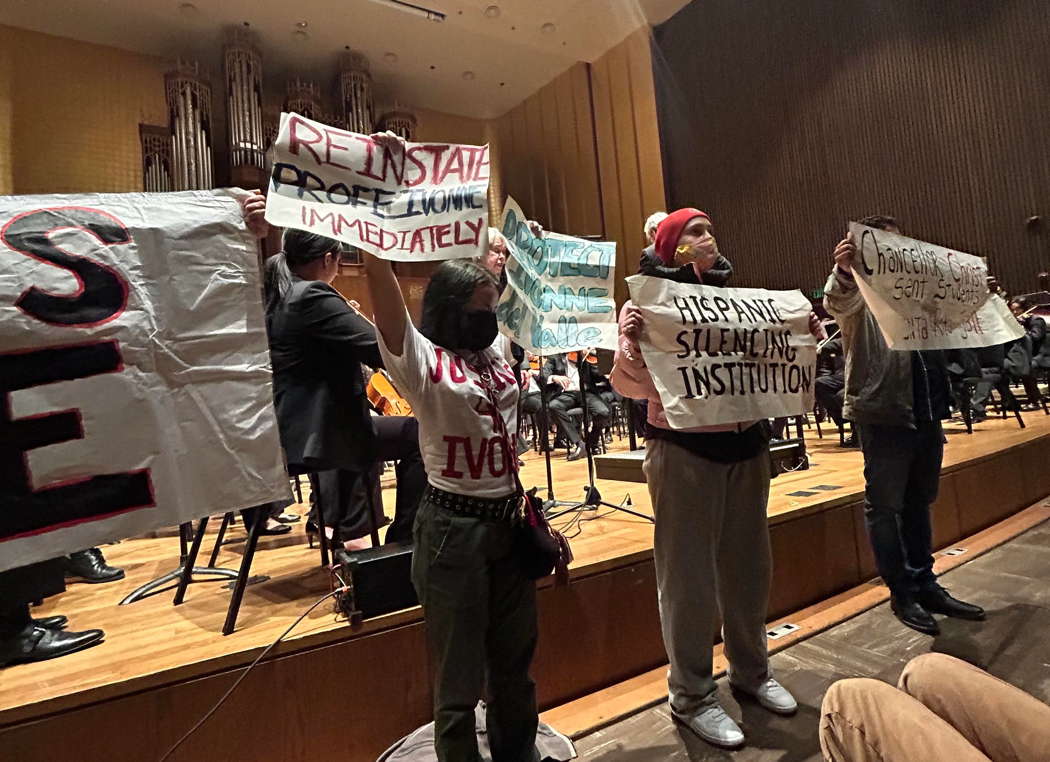

The protest at the UCB Symphony Orchestra on 3 November 2023, asking for Professor Ivonne del Valle to be reinstated.

Doctoral student and violist Saagar Asnani perceived it somewhat differently:

I don't think our orchestra really minded their presence. The protestors had a right to courteous protest, which they exercised (except for the shout at the end). Had they simply left quietly, I don't think it would have been much of an issue at all.

The protest got me thinking, first about why it felt like a violation of a sacrosanct rule, that everybody off the stage should be imperceptible - seen and not heard. There is a tacit shared belief among contemporary classical music audiences that the purpose of the concert is primarily, if not solely, to experience 'personal feelings of sublimity', as the BBC's Tom Service explains in his segment, 'Why Are Classical Audiences So Quiet?' But I wondered if protest and communal expressions of joy or angst could play a more vital role in the concert hall at a time when global strife is roiling the world.

Tom Service

On the way to the performance I walked by dozens of police cars on campus, demonstrating that protest is perceived as combustible, needing to be contained by force if necessary and kept out of the lecture halls, the concert halls and the athletic stadiums where connections between people and cultural products occur. Finally, perhaps the most important question: why bother to come together? The isolation of the pandemic has become a habit, and we can't take for granted that people want - or need - to come together to listen to classical music.

Protest feels like an interruption, an unwelcome interloper that disrespects the hard work of the performers and degrades the attention of the audience. That was a feeling shared by almost everybody I talked to.

Asnani explained that the UCB Symphony Orchestra didn't want the protesters there at all:

Truth be told we were not planning to allow the protest and had increased security at our ticket check in, but it seems that our extra measures were not enough to deter the protest.

A representative from the department, who did not wish to be named, emphasizes that the protest 'was not a sanctioned part of the program' and that the Department of Music 'did not anticipate any deviation from the conventional concert setting, nor did the Department expect the audience to engage differently'. The concern of the managers was, quite understandably, 'minimal auditory disruption'.

The UCB Symphony Orchestra performing Britten's Young Person's Guide on 3 November 2023 with Carol Christ narrating and David Milnes conducting.

Photo © 2023 Ricky Chen

The emphasis on a 'conventional concert setting' and a silent audience are as much a commonplace in 2023 as they were in 1923, whether in Berkeley or London. A decades-long patron of the Oakland Ballet Len Reppond confirms this when he explains that classical music:

... must be experienced in a distraction-free environment. One's mind and body need to be relaxed and open in order to connect and experience the emotion of the piece.

In contrast, James Johnson, the author of the groundbreaking Listening in Paris: a Cultural History (1996), is a critic of the self-policing of contemporary classical music audiences. There are:

... few available behaviors except sitting there reverently, stiffly, silently, and I hate to say it, in a state of boredom.

James H Johnson: Listening in Paris: a Cultural History

(University of California Press, 1996)

Still, even he admits:

I think all lovers of music are grateful that audiences are silent. I say that as a lover of music.

Sitting in my seat in Hertz Hall, I am irritated by the protesters because I have to struggle to bring my attention back to the music. Not knowing what they will do next and worrying if some confrontation will erupt takes me away from the music.

Yet, if I am honest, these contrary emotions inside of me also mimic the mood of some of the individual instruments in the section where Britten has, according to Eric Crozier's narration, 'taken the whole orchestra apart'. There are moments of airy transcendence, of brassy discontent, and of percussive temper-tantrums. However, the stressor of a group holding protest banners smothers my experience of playfulness and celebration. That's a shame because in that sense I am missing at least half of what Britten's instruments are stirring up. The piece celebrates art's capacity to speak from one age to another: Henry Purcell's English Baroque to Britten's post-war England.

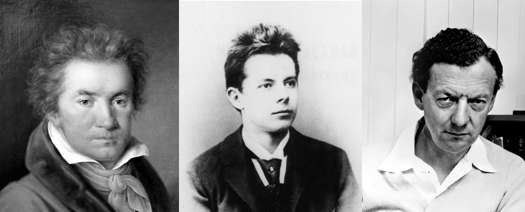

English composers Henry Purcell (left) and Benjamin Britten

It marks the end of World War II's death and destruction, followed by hope in the potential for young people to learn to listen - and then to perform or compose new works. It is a tribute to the capacity of art to refine our sensibilities, even as the hatred and violence of war degraded it. And it reminds us at the most basic, foundational level that the orchestra is composed of different sounds that alternately move away from each other and then come together. There is conflict; there is playfulness; and there is a celebratory spirit all coming together.

It's this musical and social fugue that interests me and suggests there may have been a missed opportunity here for the orchestra to integrate the conflict of protest. In this case, the pieces performed on 3 November 2023 - Britten's Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra, Beethoven's Seventh, and Bartók's Dance Suite - all come out of periods of historical strife and reflect that turmoil.

From left to right: Ludwig van Beethoven, Béla Bartók and Benjamin Britten

Perhaps there is a way to integrate protest and strife, audience reactions and sounds, to allow performers and their patrons to shed the ascetic reception practices that differentiate classical music performances from, say, a jazz concert or a pop concert.

The largely student audience seemed actually quite at ease with the protest. There were no strained necks or uncomfortable coughing. One young man casually recorded the hubbub on his phone, alternating between his gadget and the performance. Afterwards, I wondered if there was a generational divide between how we listen - with younger listeners nimbler at moving between their gizmos and the stage - the virtual world and the virtuoso. However, I am soon disabused of this. Amber Lin, a precocious fifteen-year-old pianist from Irvine, who has performed at Carnegie Hall, provides me with a list of things she recommends for experiencing a classical music concert: Observe how other people are behaving and copy them; don't clap unless the performer has indicated they have finished the piece; stay off your phones; sit respectfully in the hall. She concludes, 'It's really important to focus on the performance itself'.

This young musician's comments don't mark a shift in ways of listening, as I had anticipated, but an affirmation of 'stultifying conventions' around listening to classical music', as London School of Economics professor Richard Sennett puts it. Rather than the clapping, whispering, shouting, bodily movements and expressions of emotion that characterized Mozart's audiences, what we have starting in the 1820s is the beginning of a deathly quiet, an unwritten rule to subjugate oneself. Sennett sums it up: 'Public life falls silent in the 19th century'.

In the previous century, the expectation was that if you were out in public, you were also available to talk; strangers would grab each other in public before asking a question. All this changes because of the political fears that come out of the many revolutions of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Thereafter, people want to be alone in public. 'Silence and solitude translates itself into what happens inside theaters.'

I can point to other catalysts for the move toward silent audiences: transcendental philosophy, Romantic poetry, Wagnerian opera and the popularity of the novel all probably fostered a sense of an increasing distance between what is going on inside of oneself when one is experiencing art and the groups of people outside. There has been a long trend away from a corporal experience of classical music, where the audience freely moves, makes noise, interacts with each other, and expresses its emotions to each other with the music and to the musicians. Classical audiences have been coerced into a 'poisonous sense of prohibition that arguably has almost killed the art form', according to Service.

Protestors at the concert on 3 November 2023. Ivonne del Valle is professor of colonial studies at UC Berkeley, currently on administrative leave after being accused of sexual harrassment.

The pandemic may have hastened that retreat into the self. After several years of listening to music alone, we have to ask ourselves, why bother going back to the opera house, the symphony hall, the churches, or public spaces where classical music is usually performed? A perfect storm is threatening even the idea of a public performance of classical music: people are more isolated working at home; there is an increased sense of loneliness, but also of inertia to break out of it; discomfort and social awkwardness are pervasive; the urban centers where classical music is often performed are more crime-ridden; and, finally, politics and wars are making people want to retreat further. If the trend over the centuries has been to a greater sense of privacy in public, the last few years may drive people out of the public altogether.

'Our listening needs to be noisier and therefore more respectful of our place', concludes Tom Service. Perhaps this is the answer to our sense of isolation, solipsism and mutual distrust as well. I go back to the image of the chancellor narrating lyrics to Britten's Guide with a full house witnessing a group of protesters, who probably felt like they were being left out of the celebration of culture at the University, their beloved mentor and professor having been exiled. 'These are very tricky times we live in ... for voices to have agency that don't have a platform', explains Jonathan Nadel, a University of California-Davis lecturer and voice coach. There are powerful challenges to 'what was considered traditional Western civilization and education and movements that feel like they have not been heard enough'.

The lyrics to The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra have been frequently rewritten and interpreted since 1946, just as Britten interpreted Purcell - a musical and verbal conversation across the ages. At the end of Britten's piece, Crozier explains:

In these variations, we have taken the whole orchestra to pieces. Now we are going to put it together again with a fugue.

Symphony halls could be one place where the quarantine mentality of extreme isolation is challenged. In May of this year, US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy announced an 'epidemic of loneliness and isolation', which has been 'an underappreciated public health crisis that has harmed individual and societal health'. The significant health consequences mean that 'we must prioritize building social connection the same way we have prioritized other critical public health issues such as tobacco, obesity and substance use disorders'.

Just bringing some awareness to what is already happening in a concert hall or opera house can begin to restore that sense of connection.

Nadel says:

There is a shared community and humanity in an audience sitting together to watch a performance, breathing the same air as great artists.

The possibilities for connection could be pushed further by explicitly introducing the history behind a piece to an audience. Andrew Shin, the young violinist, is also excited by the idea of a 'synergy' between the historical events that inspired a piece, like Beethoven's Seventh, and what might be happening in the world today.

Amber Lin imagines that:

if the protest had a similar theme to the music, it might also engage the audience.

Rather than banishing the turmoil outside, classical music concerts might help us to process the intensity of emotions of rage, frustration, impotence, fear and distrust that are surging in public spaces today. This would involve some connections being made for us, and stepping out of a safe space, perhaps even risking 'being cancelled', a fear that both Lin and Nadel mentioned as possibly influencing the behavior of the musicians and directors who have to make these choices.

The #Justice4Ivonne campaign has been protesting since August 2023

It might also be enough to induce a group catharsis just loosening the expectations of silence for the audience - a return to a time as far away as Aeschylus' Athens or as recent as Beethoven's Vienna.

Asnani ruminates:

I'm not suggesting a complete return to the concerts of Beethoven's time is in order, but rather that we certainly have made concert halls too stuffy! To the point where a cough out of place garners glares from your fellow concertgoers or clapping in between movements is nothing short of a faux pas. What if instead we fostered a welcoming environment where people would want to come enjoy the music?

After Covid, this is a crucial question because if the purpose of listening to music in a concert hall is simply better acoustics, that may not be enough to bring people back to their seats. However, being able to vent powerful feelings, make connections between the historical context and the present, and having the permission to let loose a little could restore to concert halls the transformative role they once held.

Copyright © 19 November 2023

Jeffrey Neil,

San Francisco Bay Area, California, USA