- Stravinsky: The Firebird

- G B Martini

- Robert Carsen

- Croatia

- Bliss

- spoken voices

- Proteus Ensemble

- St Nazaire

A Unique Sense of Bravado and Fun

RODERIC DUNNETT reviews Purcell's 'The Fairy Queen' at Longborough Festival Opera

Longborough Festival Opera is a sparkling national treasure, and has been ever since Martin and Lizzie Graham embarked on a dream adventure, to create an exquisite privately funded opera house - a masterpiece of entertaining design, incidentally - right there on their own field, with no public subsidy, and lure what is now a massive, enthusiastic following for what has - justly - been dubbed 'England's Bayreuth'.

An inspired view of Longborough Festival's Opera House taken from near New Banks Fee, the Grahams' elegant home in the Cotswolds erected and enlarged by Martin Graham himself

The courage and flair are typical. For it was Wagner, and above all his gargantuan, four-part Ring cycle, who gave the impetus to this staggering enterprise, as much as a quarter of a century ago. Siegfried and Brünnhilde in a barn. Overlooking the once battle-scarred Vale of Evesham? It sounded daft. Risky. Crackers. Unhinged. Foolhardy. Crazy?

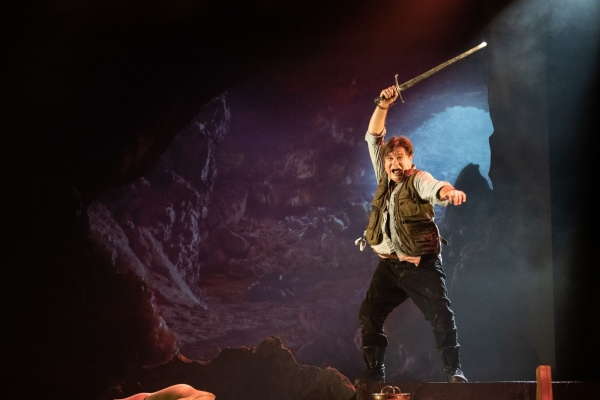

Australian tenor Bradley Daley, stirring in the title role of last season's Siegfried at Longborough. Photo © 2023 Matthew Williams-Ellis

But it wasn't. Or alternatively, it was several of these. Wisely, the orchestra pit being not as vast as it is now - much further digging out soon went on - Martin Graham began with a kind of makeshift, reduced-format Rheingold, employing Jonathan Dove's clever, compact version, and fascinating (side) surtitles which in a few words gave the gist of each scene: 'Amulet', 'Loge', 'Hammer', 'Danger', 'God', 'Wicked', 'Rainbow' - that sort of thing. I rather long to see that ingenious version again.

Those early years featured to my mind one of their best Wotans - not just commanding but unusually vulnerable, not least as Siegfried's Wanderer: Brian Bannatyne-Scott. Amazingly Sir Donald MacIntyre - the real Bayreuth! - followed. But their greatest asset has been capturing and keeping a wondrous, unbeatable Wagner conductor, Anthony Negus - at that time a lynchpin of Welsh National Opera, but earlier an apprentice to a real Wagner legend: Sir Reginald Goodall. Reggie's legacy is the brilliant intelligence and sapient insight of all Negus's meticulous interpretations. It's the Grahams and Longborough who have made it all possible.

Fast forward to now: Longborough is poised to stage its third complete Ring cycle in 2024. Their policy, such a sensible one, has been to build towards these by stages annually. Hence in year two, Rheingold is paired with Walküre; the next, a new Siegfried plus the existing Valkyries revived, and so on. This culminated in their first full Ring in 2002, and their second in 2013. The magnificence of Longborough's success in championing Wagner thus is enough to aghast and astound. Flabbergasting: a marvel.

And in the years between, other Wagner has appeared on the Cotswold ridge: Tristan in 2015 and '17; Tannhäuser in 2016; Holländer (The Flying Dutchman) in 2018. So intimate and heartwarming is this vivid Longborough tradition, one tends to feel it a swizz when there's no Wagner during the odd year. Yet there must be so much still to come, and relish: Lohengrin, Das Liebesverbot - Measure for Measure: it's been staged by young performers - the equivalent of Longborough's Emerging Artists - at Bayreuth; and surely Die Feen - the twenty year old Wagner, and superb; although Meistersinger and Rienzi - more massive - call for a grander space; maybe Parsifal as well.

Given that Longborough relies totally on private support, not Arts Council subsidy, it is miraculous what efforts it has made, no, steps it has taken, to create a youth element comparable to, indeed equalling, what subsidized companies have over the years been egged and prodded - pushed and shoved - into accepting by the threat of public cash withdrawal (though the benefits generated have been substantial). Still, the extent of Longborough's outreach is almost unbelievable.

For some years we have been charmed, but also profoundly impressed by the productions - usually one a year - centred entirely on younger performers: in essence, those embarking on a career on and offstage. And in challenging repertoire: Monteverdi's Poppea, immensely skilled and memorable; Handel's Alcina: and Rinaldo, then Xerxes: and what talent. A sensational undertaking. Cavalli's La Calisto; Gluck's Orfeo. Musicals too, but the Baroque are the ones that impinged most on me.

The very first was for much younger performers - Britten's Little Sweep - a sweet, a bit twee but touching staging. And it is to these youngsters that Longborough has so wonderfully extended its outreach. Only recently their 'Playground Opera' yielded a production of a quasi-Carmen, focused on her hapless lover - 'The Downfall of Don Jose'. There is a phenomenally active Youth Chorus, professionally prepared, nursed and encouraged.

The youngest, who may in time make the leap to join the older groups, are introduced to the finessed, world-famous Kodály method, which has been in use for singing by youngsters in Hungary for decades, its success recognized by a (still smallish) number of groups in the UK and America. And here is Longborough revolutionising musical instruction in local schools at a time when music education, let alone individual instrumental lessons, has recognizably diminished in lower institutions.

The intention, clearly, is noble. 'To raise standards, nurture talent, encourage creativity, develop young voices, introduce to performance skills, supply an unique opportunity to appear on stage, and to collaborate with professional artists.' Could one ask more? One is overawed by such excellence, not just of intention, but of achievement.

Gluck's Orfeo was mentioned above - Young Artist staging, 2017. And bringing Monteverdi's astoundingly groundbreaking Orfeo was one of the highlights of 2023. But alongside it came the latest Young Artist event. Back to the Baroque: a version of The Fairy Queen, Henry Purcell's witty and elaborate - some might surmise obtrusive - music designed for a performance of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Longborough youngsters having fun.

Photo © 2023 Matthew Williams-Ellis

Longborough quite amazingly remains a family affair. In fact New Banks Fee House is a home to artistic talent. Riddled with it. If Anthony Negus is the crucial mainstay of the music, abetted by younger figures such as this year's conductor, Harry Sever, the adoption of Polly Graham, scion of this remarkable household, the eldest of three, as Artistic Director has turned out to be one of their triumphs.

Her award-winning youthful megatalent has been firing up over the past decade. One has only to think of her staging of a superlative, totally neglected opera, Karl Amadeus Hartmann's Simplicius Simplicissimus, a heartbreaking story of a young boy caught up in the savagery of the (early seventeenth century) European Thirty Years War - the World War of its time - to perceive her audacity and drive.

With additional training and opportunities in California, Poland and Paris, she has cut her career with recent and contemporary opera: apart from the Swiss Frank Martin, for instance, witness the much-commissioned, now senior Italian composer Pierangelo Valtinoni - eight operas to date - and especially the significant modernist Olga Neuwirth, a big name in Austro-Germany, from an equally artistic family to the Grahams, born in Graz, a city frequented by such as Nikolaus Harnoncourt; known in Britain at The Young Vic, ENO and the BBC Orchestras; and a friend of and learning from the equally talented German Adriana Hölszky, much influenced by the modernism of Darmstadt Summer School and currently Professor of Composition at the Salzburg Mozarteum.

Longborough's latest wheeze has been a staging - with its young performers - of Purcell's (sometimes hyphenated) The Fairy Queen. How much of Shakespeare's 2,800-odd lines featured in Purcell's fancily, and expansively-staged 1692 Dorset Garden semi-opera - he amended and improved it the next year - is not certain, but his music introduced additional text and vocals.

It's not easy to pull off. Whom or what does one cut? Purcell's (or his unknown librettist's, possibly Betterton's) Drunken Poet, mysterious beings, shepherds, orientals, four seasons, a marriage blesser, two deities can get in the way of Shakespeare's clear plot and sub-plots. Some have condemned the whole semi-opera as sacrilege and a shambles. (A few thought that about the original play.) Decisions and tosses of a coin about how to interweave the music with the original require some shrewdness.

Instruments and actors intertwine onstage in Purcell's The Fairy Queen at Longborough. Photo © 2023 Matthew Williams-Ellis

What seem to be needed each time it is revived, are a fresh treatment, fresh ideas and fresh humour. Certainly this production ticked those boxes. All four lovers (of course), and the tangle they get into was pretty adroitly and amusingly handled. The fairies were out in force: soprano and mezzo (both Welsh, as it happens); all the Mechanicals (who of course filled the auditorium with side-splitting ridiculousness after the interval); even Theseus, Hippolyta (restored; Purcell deleted them) and the (supposedly) Polonius-like, crusty figure of Egeus (Suzie Purkis) got a look in.

The set and props (by Nate Gibson, to whom we owed the spellbinding, claustrophobic set for Korngold's Die tote Stadt last year) kept springing surprises; indeed he designed the awesome, heartless K A Hartmann in London for Polly Graham, and Janáček's Vixen at Longborough before that; and even the doomed Auschwitz-bound, courageous Entartete Musik composer Viktor Ullmann. Darkness was not a bonus, and any sense of a wood was modified to a largely, perhaps deliberately dreary, soulless playground; not a hit in itself, but consistent with a sort of 'green' message championed at the start, suggesting the world was on a loser. Mercifully the very opposite of the frisky, colourfully-clad cast. Shakespeare's 'hybrid' triple plot linked at times into not so much an absorbing interaction as a bit of a jumble.

Eerie darkness - to lose oneself in - Purcell's The Fairy Queen at Longborough. Photo © 2023 Matthew Williams-Ellis

The music was utterly secure, thanks patently to hard and imaginative scoring and preparation in ideal spirit by conductor Harry Sever and his assistant Naomi Burrell. Not even ten instrumentalists, yet the individual solos or duets and the ensemble passages as well yielded endless variety. Purcell needs that: and he got it, handsomely. Amongst notable credits, Sever has appeared in two main Danish cities, Esbjerg - Wagner's Siegfried, as it happens - and Aarhus, the location of Denmark's 'National Opera': the 'Royal Opera' is in Copenhagen. His next treats include Strauss's Ariadne (for Opera North) but - even more - Scottish Opera's Daphne, a supernatural and mythological late (Dresden, 1938) Strauss opera staged with stunning impact by Leonard Ingrams at the original Garsington - surely one of the spurs for the Grahams' creation of the joyous, daring Longborough. Sever's is proving something of a meteoric career.

Angharad Rowlands and Alys Mererid Roberts - fairies doubling as Quince, Flute, unless one feels Thisbe must be a cross-dressed male to steal the show, attract a lot more laughs and add a Classical feel - both shine among the bizarre rustics, with George Robarts hee-hawing as bossy, hopeless Bottom/Pyramus. The projecting large ears attached to him, rather than a complete donkey's head, worked perfectly well, as they have done elsewhere. Starveling and Snout, both differently characterized from the usual, doubled as fairies too. (Likewise, Purcell's original cast each assumed several different roles.)

It has to be admitted some of the aspirations of this production weren't exactly matched. It was a delight to have thirty-four young things participating in bits of the action, but the 'magic wood' became at times - well, overloaded. This 'image of abandoned theme park' felt a match for a skateboard rink stuffed with anybody to hand. The tension between play and semi-opera became more a puzzling fusion. Crazy things certainly befell amid the trees, but 'peripheral, liminal'? More crammed and hollering. Conceivably the five acts of Purcell's original 'plotless masque' were beautifully, impeccably mapped out - especially given the notorious, Lully-like expense. Well, not entirely here, although with tremendous energy and thrust.

As in Shakespeare, the lovers' utter confusion played a large part early on: Lysander and Hermia - Peter Edge and Eleanor Broomfield - quite chirpy, Helena of course lugubrious, yearning and downcast (Annie Reilly), were intermingled with Purcell's almost insane interpolations - eg a trio much like his most scurrilous catches, 'fi-fi-fill up the bowl'; 'enough, enough, we must play at blind man's buff'; 'pinch him ... pinch him for his crimes, His Nonsense, and his Dogrel Rhymes'. The scurvy Poet has his riposte: 'Good dear Devil, let me go'. And the chorus has a line surely echoing Oberon in the original: here, 'Let 'em sleep till break of Day.'

Some - not all - of the blocking of this scatty ensemble worked particularly well. So did the chorus's not-quite syncopations - a kind of Scotch snap (ie emphasizing the first, not the second, beat): terrifically pert, bouncy and very effective; likewise Puck's ensuing solo (Suzie Purkis) - she, as all through, delightful. Another block, round Titania, both clever and beautiful, and unexpected (sudden back curtain collapse). Sever and Burrell's orchestration for the admirable Early Music Company - which includes Dido and Aeneas and Blow's Venus and Adonis in its repertoire; its late founder edited The Fairy Queen on which this version was based - allowed for an accordion - amazingly entrancing, not least when paired with double bass, which created some lively pzazz. As well as lute and stylish guitar, there was a wealth of invention in this treatment of the music, which enhanced things no end.

Likewise the Song 'Gives more delight than a hundred lucky days'. It's generally agreed that The Fairy Queen is one of Purcell's finest, cleverest scores. Perhaps a tall order when one considers Dido's ground bass, the 1694 Funeral Music for Queen Mary, and almost all his church verse- or choir-only anthems. But the claim is made mainly with regard to his stage scores - bettering King Arthur, Diocletian etc.

One song with chorus that surely justifies such a claim is 'Hush, no more, be silent all, Sweet Repose has closed her eyes' (Titania), but joined in mysterious wonder - magical - by the whole brigade; and then the expressive, commanding 'Hark ... no more', in which the effect is similarly and wonderfully calming. One thing that must be approved: the enunciation was simply excellent from all, leads and extras, old and young and littluns alike. Someone (the Youth Chorus team?) had clearly done marvellous work with them. All of them, without exception.

'If Love's a Sweet Passion, why does it torment?' is a ballad that could be straight out of John Gay's The Beggar's Opera. Gay was born ten years before Purcell died, and 1728 is not so far distant from this teasing stagework. This ensemble piece - almost a Sonnet - starts with Hermia and Lysander, grows to an appetizing quartet, before others muscle in, and of course was sheer delight. And more evolved, with Helena instead making touch with her longed-for Lysander - and ending up being chased ('Captain of the fairy band, Helena is here at hand ...') by both the beaux. 'Up and down, up and down', delivered by Puck, and by Shakespeare, not Purcell or Betterton, furnished more enchantment.

And time and again, the instrumentation served up treats. Cello, keyboard and archlute, like a charming continuo. Or an interlude for what sounded like two pipes, but was perhaps just the very lovely one recorder (Adrian Woodward). Delicate vocal offerings, solos or in duet or more. Trumpets, and pipe(s) - 'Let the Fifes, and the Clarions ...' - added spice at every turn, Woodward somehow playing both. A massive full orchestral sound (from so compact a group) was dazzling.

What with Gibson's eye-befuddling properties, collapsing arras, a great pink paper flower for Oberon's comic machinations (Lars Fischer), the braying donkey, a battle royal - with toothbrushes, a kind of Punch and Judy tryst with particularly huge masks, a whopping, Lohengrin-quality swan, a gigantic multi-flavour ice-cream cone, silver stalactites for the overhanging 'trees', plus a host of wacky contrasting costumes, not period but in a sense too freakish, exuberant and inventive to be called 'modern dress' (plenty of Sixties-type let-your-hair-down feel), there was ample visual fun.

Titania (Rachel Speirs) riding the giant swan in Purcell's The Fairy Queen at Longborough.

Photo © 2023 Matthew Williams-Ellis

And - to contrast with some of the most delicate songs, and intended by Purcell to embrace the appearance of Hymen, to bless the triple marriage - all turns joyous: 'Hark the Echoing Air', 'Turn then thine Eyes upon these Glories here' (solo and chorus, then duet), capped by the nonsense of the 'Rude Mechanicals' hilarious love exchanges - Bottom, Flute, backed up by earnest Wall (Rhydian Jenkins), ridiculous Lion (Purkis swapping from Puck) and a battling (rather than traditionally doddery) Moonshine (Edward Jowle) - any visual twaddle was totally justified. Mystifyingly a hit? Well, the audience thought so.

A production in flow at Longborough Festival auditorium.

Photo © 2023 Matthew Williams-Ellis

To recap: Longborough's vision in staging Erich Korngold's Die tote Stadt in summer 2022 (even if ENO, uncharactistically these days, mounted it weeks later, in English) does lead me to this, to my mind, significant point. It has always seemed to me this - its superb Ring apart - is exactly what this original-thinking, wondrous opera house should, or could, be focusing on. And to get away with a title like Dead City easily proves the point.

Erich Korngold's stunning Die tote Stadt - Marietta (Rachel Nicholls) entrances Paul (Peter Auty) by mimicking his dead wife, Marie.

Photo © 2022 Matthew Williams-Ellis

I have mentioned this, with some passion, in conversation with Anthony Negus, and repeat it below. For an impresario with such a passion for German opera as Martin and Lizzie Graham have shared with us, La bohème (in 2024 with the magnificent complete Ring) is not what this stupendous venue should be about: even with their so satisfyingly versatile Youth Chorus.

The Grahams, by massive hard work, aplomb and initiative (and - relished by all - a unique sense of bravado and fun), have garnered a superb, substantial gaggle of followers. And whatever such a justly renowned company puts on, people will trustingly and devotedly come. Audience-pleasing? No. Leadership? Yes. Così? No. Figaro? No. Flute? Not really. La Traviata? Ugh. Carmen? Never. Maybe not even Janáček. Fidelio (2017)? Yes, a must. Their Handel, for young artists, has been matchless from the very first.

But their impact at the outset came from that bravado: they assayed what nobody else has done. And that courage, that determination to share operatic richesses is what makes them special. The wealth of German opera Longborough audiences - mostly hits in their day - could be led into is unbelievable. Polly Graham has already proved that, superbly elsewhere, with Karl Amadeus Hartmann.

Schikaneder without Mozart (there are loads, surely hilarious). Weber, Lortzing - lots, tuneful, like Schumann - Buxton recently had a peep. Marschner, Kuhnau (Lulu - fabulous like early Wagner), ETA Hoffmann Schumann himself (Leonard Ingrams staged Genoveva - first UK professional performance, June 2000). Humperdinck - gosh. Kienzl. Zemlinsky. Wagner's own son, Siegfried. Braunfels (The Birds), Schreker, Pfitzner, D'Albert, Hindemith, Krenek, more Korngold. The rich, rarer, later Strauss. All frankly wonderful. These were Wagner's successors, and could be advertised/promoted as such.

For Longborough's fine and dazzling reputation for uniqueness and exploration to be upheld - and further enhanced, as Tote Stadt proved - this is, possibly, where to look.

But Britain's Bayreuth marches proudly on.

Copyright © 4 September 2023

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK