CENTRAL ENGLAND: Mike Wheeler's concert reviews from Nottingham and Derbyshire feature high profile artists on the UK circuit - often quite early on their tours.

CENTRAL ENGLAND: Mike Wheeler's concert reviews from Nottingham and Derbyshire feature high profile artists on the UK circuit - often quite early on their tours.

Ronald Stevenson

A little memory, a little overview and a little comment

I'm not sure what I was actually looking for on that day in the mid-1970s as I wandered the bookshelves of the University library. But, what I found was the Passacaglia on DSCH by Ronald Stevenson (1928-2015). I opened that music and my situation altered utterly. I ordered my own copy shortly thereafter and it has been either on my piano desk or next to my piano ever since. I have consulted it hundreds - no, thousands - of times.

Now by an odd circumstance a short time later I was browsing the music scores at a small shop and what should I find, but a copy of Ronald Stevenson's Prelude, Fugue and Fantasy on Busoni's Doctor Faust! Needless to say I bought the music and spent countless hours playing through it, studying its ideas and doing my best to absorb its meaning. Needless to say, the Passacaglia has also undergone similar ongoing and long term study.

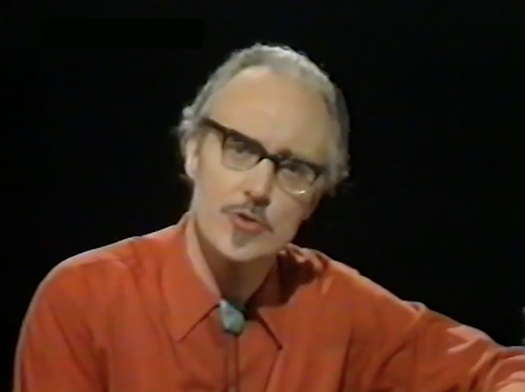

Ronald Stevenson introducing his 1974 documentary about Busoni

In the 1980s when I wondered where I should study, one possibility was seeking out Ronald Stevenson, but in those pre-internet days I could find no-one who could put me in touch with him. In the next cycle of this same Universe (according to the ideas of the ancient Stoics and P D Ouspensky) I shall make greater and more effective investigations.

Still, the music became a major source of my own manner: I am a feverish user of symmetrical inversion in my compositions and the spirit of Ferruccio Busoni is never far away. I have done what I can - little though that be - on behalf of his wonderful music.

His achievements as pianist, composer, author, teacher and musical sage are beyond description. Just a brief gander through his works list in the excellent biography and series of essays published by Toccata Press will make one's head spin.

Taking up the composer/pianist mantle of the nineteenth century, Stevenson excelled at both and used both to inspire and enrich the other — this is why pianists are always better pianists when they are good composers and why composers are always better composers when they are good pianists (or other instrumentalists, of course).

He created a vast repertoire of piano music, where each work is scrupulously marked with sophisticated fingerings, pedalling, articulations and performance indications such that each score is a lesson in interpretation.

He created a giant body of song for solo voice that demonstrates a loving manner of musical melody. His choral works, though demanding, are hauntingly beautiful.

Along with his many original compositions Stevenson also transcribed countless works from one performing force to another: piano to organ, lieder to solo piano, orchestra to solo piano, solo piano to orchestra and so on.

He was cognizant with the whole of Western Music, but also knew much of other musical cultures as well.

Compositional method

Stevenson was deeply influenced by Busoni (indeed there Stevenson wrote a massive biography that awaits publication if I am not mistaken), and Busoni was deeply interested in the symmetrical inversion methods of the German American theorist Bernhard Ziehn. Now, symmetrical inversion is very interesting and was certainly not invented by Ziehn. Rather it is the use to which these three put this device (and others did as well, such as Ernst Bacon). The idea was to create a wider range of harmony and memory for the listener. For musical ideas in symmetrical inversion sound similar but are not always instantly identifiable. The result is a certain dislocation of response (“Is that what I think it is?”) and an increase in compositional depth; contrast through similarity, if you like.

But, there is another philosophical point, which I am not sure I have seen mentioned in the literature and which I did not feel appropriate to ask Dr Stevenson when I visited him. You see Stevenson was a longtime follower of those political ideas which sought an inversion of the political system with the demotion of the aristocracy and a promotion of the proletariat. I find the use of symmetrical inversion a very precise musical metaphor for this political ideation.

These are all observations well known to anyone who has read a simple biography. I should return to my own experience.

Hearing him perform in concert was difficult as I live in a remote locale, but an almost 1,000 mile drive enabled me to attend a performance. The beauty of his tone, the perfection of his legato and the myriad colours he could evoke were stunning and astounding. His technical command was formidable. And this was a few years after he had suffered a debilitating stroke. He told me after the concert - where there had been not a single instance of pianistic weakness, but a whole concert of total pianistic command - that after the stroke he had used his memory of the piano to reteach his body to play again, for he knew what the piano sounded like, what it felt like and his body needed only re-education after the stroke.

I met him once more at his home in Scotland where he and his wife - the indomitable Marjorie - hosted me with grace and kindness for many hours. I heard tell of many matters related to composition, performance practice, the music of Busoni, the piano-playing of Paderewski and his own compositions and approach. These are hours I will not easily forget.

But forgetting is easy. That is why so many Teachers of Wisdom advise us To Remember. This essay is a work of remembrance.

But, is he being remembered as is his due as a great creator in our modern culture?

There are now the better part of a dozen recordings of the Passacaglia which is an enormous exertion and great achievement. There are now several books about him, or drawing on his life and work. More recordings are coming out and I bless the musicians for taking up this challenge. The Ronald Stevenson Society exists and one can purchase a large percentage of his enormous creative output.

And yet, there are days when I lament that he is not as widely known as I feel he should be. Perhaps it is because the pop-culture tsunami makes us know about movie stars, rock stars, the latest novel prize winner or best seller. And while we know these, and know them very well - just ask an aficionado to tell you about their favourite Heavy Metal band and its style - I wonder why such an artist as Stevenson might not be forefront to our listening.

Perhaps the appearance of the Passacaglia, performed first in 1963, which should have been an epochal moment, was buried by the pop culture storm of The Beatles - founded in 1960, with first hit by 1962 and world famous by 1964 - that crashed over the world. I think it is an interesting coincidence of timing, don't you? We certainly were pressed along with the tidal wave of The Beatles et al, but one wonders if there was a different path we might have taken?

Ronald Stevenson's achievement is a great treasure to our musical culture.

Remember.

Passacaglia on DSCH

Performances/Recordings exist by:

Ronald Stevenson

John Ogdon

Raymond Clarke

Murray McLachlan

James Willshire

Igor Levit

Mark Gasser

Shota Ezaki

Richard Black

(These are the ones I know of. There may be others. No slight is intended by omission.)

Ronald Stevenson resources

Toccata Classics books:

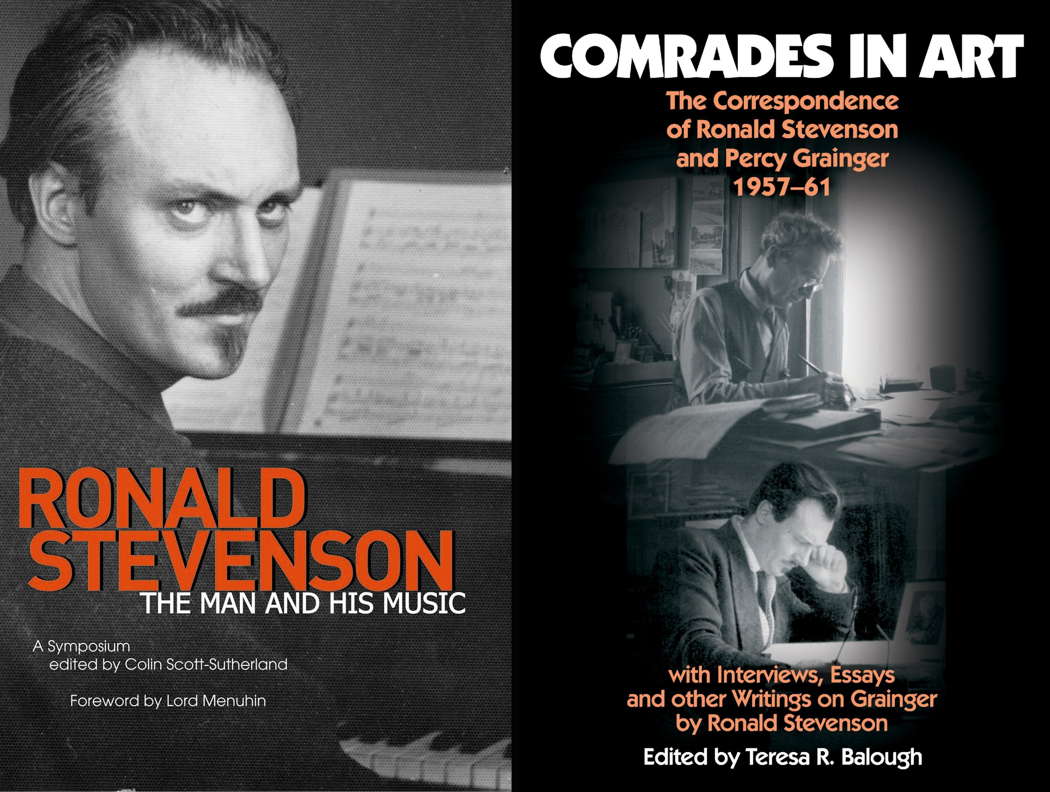

Ronald Stevenson: The Man and His Music

Comrades in Art: The Correspondence of Ronald Stevenson and Percy Grainger 1957-1961

Toccata Press book covers for Ronald Stevenson: The Man and His Music and Comrades in Art: The Correspondence of Ronald Stevenson and Percy Grainger 1957-1961

Toccata Classics has also released numerous CDs of Stevenson's music.

Published on 28 March 2023 - the author wishes to remain anonymous