- Sarnia

- Riccardo Muti

- Carboneu

- Ernstalbrecht Stiebler

- Charles Mackerras

- Starker

- Wolfgang Gönnenwein

- Katie Smith

Kaleidoscopic Variety

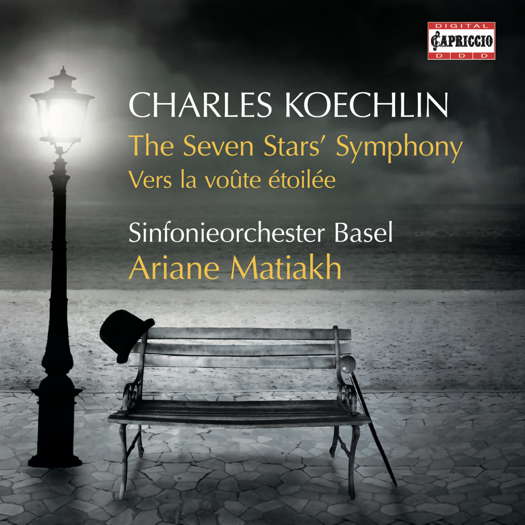

GERALD FENECH listens to music by Charles Koechlin

'... a near uncontrollable energy that almost brings Chaplin and Co back to life again.'

Charles Koechlin once said: 'The artist needs an ivory tower, not as an escape from the world, but as a place where he can view the world and be himself. This tower is for the artist like a lighthouse shining out across the world.' Charles Koechlin was born in Paris on 27 November 1867. He was the youngest child of a large family. His mother's family came from Alsace, and he identified with that region; his maternal grandfather was a noted philanthropist and textile manufacturer, and Koechlin inherited his strongly developed social conscience. His father died when he was fourteen. Despite an early interest in music, his family wanted him to become an engineer. Consequently he entered the École polytechnique in 1887, but the following year he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and had to spend six months recuperating in Algeria. He ended up doing his first year at the École once again, but only graduated with mediocre grades. In the end he got his way, and in 1890 he entered the Paris Conservatoire to embark on his musical career. He studied composition with Massenet and later Fauré, and his fellow students included Enescu, Hahn and Ravel.

In 1910, together with Ravel and Schmitt, he was one of the founding members of the 'Société musicale indépendente, a more progressive organisation for French musicians than the conservative-leaning Société nationale de musique, established in 1871.

At first Koechlin was comfortably off, but the First World War hit him hard and he had to sell one of his country homes. In 1915 he began working as a lecturer and teacher, but partly because of his constant advocacy of younger composers and new styles, he never succeeded in getting a permanent teaching job. He visited the US four times to lecture and teach: in 1918-19, 1928, 1929 and 1937.

Despite paying out of his own pockets for the preparation of orchestral parts, only a handful of his works were performed until the 1940s, when the music department of Belgian radio took up his cause and broadcast several premieres of important scores, including the first complete performance of the Jungle Book cycle. Koechlin died on 31 December 1950, aged eighty-three, still underrated and underperformed.

In both musical and political terms, Koechlin was a lifelong progressive, if not always a radical, firmly rooted in the musical language of French impressionism, but open to all manner of eclectic influences, albeit with a distinctly Gallic flavour. Without doubt he was one of the great orchestrators of his age, and the crowning opus of his vast output is an ambitious choral-orchestral cycle based on Kipling's The Jungle Book.

On disc, Koechlin's music has been represented only sporadically and many a time patchily. All this makes this new recording of two of Koechlin's finest orchestrated works particularly welcome. Composed in 1933, Vers la voûte étoilée (Towards the Starry Vault) is a thirteen-minute orchestral version of a piano nocturne, gorgeously scored and dreamily evocative. Full of impressionistic colours, the work possesses a Fauré-like delicacy, and there are also shades of Liadov and Rachmaninov, particularly the latter's Isle of the Dead. Incredibly enough, this splendid creation had to wait till 1989 for its first performance.

Listen — Charles Koechlin: Vers la voûte étoilée

(C5449 track 8, 0:02-0:56) ℗ 2022 Capriccio :

The main work on this memorable disc is another 1933 orchestral wonder, The Seven Stars' Symphony. Unlike Vers la voûte étoilée, this has nothing to do with Koechlin's lifelong fascination with the heavens. It's a celebration of seven famous screen performers from the early years of the silver screen. Although the composer himself initially disdained silent films, dubbing them vulgar and demagogic in nature, he came to appreciate the 'spiritual grace' and 'insolent beauty' of certain stars. Three of the 'divas' celebrated here – Lilian Harvey (with whom Koechlin was particularly infatuated), Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich – successfully managed the transition to the 'talkies', while the last, Charlie Chaplin, was a cinematic genius whose work transcends such distinctions. Interesting is the fact that some of these character portraits evoke the stars in particular films – Douglas Fairbanks Sr in The Thief of Baghdad and Emil Jannings in The Blue Angel (alongside Marlene Dietrich) are prime examples.

Listen — Charles Koechlin: Douglas Fairbanks (The Seven Stars' Symphony)

(C5449 track 1, 0:00-0:56) ℗ 2022 Capriccio :

Whether this is a real symphony or something more akin to an expanded suite is a moot point. What we can say for sure is that the work is an orchestral tour de force that relishes the refinement and kaleidoscopic variety of Koechlin's endlessly imaginative writing.

Listen — Charles Koechlin: Lilian Harvey (The Seven Stars' Symphony)

(C5449 track 2, 0:00-0:44) ℗ 2022 Capriccio :

We must not forget Clara Bow, the seventh star, not mentioned so far, to whose charming presence Koechlin dedicated the Symphony's scherzo.

Listen — Charles Koechlin: Clara Bow (The Seven Stars' Symphony)

(C5449 track 4, 0:00-0:42) ℗ 2022 Capriccio :

The pièce de résistance of this gigantic musical canvas is the seventh and last movement dedicated to Charlie Chaplin. Koechlin came up with a multi-sectioned set of variations with frequent changes of time signature, displaying a compositional virtuosity and range of moods – zany madcap comedy, moments of pathos and reflection – entirely worthy of its subject. At fifteen minutes it is the longest movement of the symphony, almost a tone-poem in itself, that builds to a blazing triumphant conclusion that could only come at the end of the entire work.

Listen — Charles Koechlin: Charlie Chaplin (The Seven Stars' Symphony)

(C5449 track 7, 14:08-15:02) ℗ 2022 Capriccio :

Ariane Matiakh is a rising star among conductors, and has already several Capriccio recordings of neglected works to her credit, but her advocacy for this work is beyond reproach. Indeed, her vibrant conducting of Sinfonieorchester Basel has not only an exciting sweep, but a near uncontrollable energy that almost brings Chaplin and Co back to life again. Her lucid and profound knowledge of these scores allows her to expose every minute detail of this glittering array of sounds that are nothing short of spellbinding. These are works of supreme orchestral craftsmanship that deserve a long life in the catalogue, and they make essential listening for anyone interested in this fascinating figure from French musical history. Sound, notes and presentation are top-drawer stuff.

Copyright © 10 August 2022

Gerald Fenech,

Gzira, Malta

CD INFORMATION - KOECHLIN: THE SEVEN STARS SYMPHONY