SPONSORED: Ensemble. A view from the pit - John Joubert's Jane Eyre, praised by Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. A view from the pit - John Joubert's Jane Eyre, praised by Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

Experimental to Classical

GIUSEPPE PENNISI reports from Rome's Istituzione Universitaria dei Concerti

On 30 October 2021, in an almost full concert hall, there were ten minutes of applause (tilting towards ovations) after an hour and three quarters (without intermission) of music considered avant-garde in the 1960s. That it would appeal to a passionate listener about to turn eighty, like your reviewer, was obvious. It was not at all certain, though, that it would thrill the audience of the Istituzione Universitaria dei Concerti (IUC), made up, to a large extent, of professors who want great tradition (preferably of the Romantic period) and students (who applaud today's music). There was surprise (for the applause) mixed with satisfaction: success is the proof that the best of fifty-year-old experimental music, although little performed, fascinates today's audiences. It has, therefore, entered the chapter that encyclopedias dedicate to 'classical music'.

The concert was a co-production between IUC, Ferrara Musica, Bologna Festival and the G B Martini Conservatory of Bologna. The main concept was to re-propose Laborintus II, a composition by Luciano Berio dated 1965, for the seven hundredth anniversary of the birth of the poet Dante, combining it with other Berio works of the same period. The conductor was Marcello Panni. He was Berio's assistant when the work was presented at the Spoleto Festival in 1968 and conducted it several times: for example, at the Teatro Carlo Felice in Genoa, at the Teatro Massimo in Palermo, at the Sagra Musicale Umbra and at the Teatromusica Festival in Rome, as well as in a stage production directed by Luca Ronconi. He also recorded it for Rai, the Italian State radio and television company.

Composed in 1965 on a commission from ORTF (French State Radio and TV), Laborintus II takes its title from the poetic collection Laborintus by Edoardo Sanguineti. The text of Laborintus II develops some themes of Dante's La Vita Nuova, Il Convivio and Divine Comedy and combines them - especially through formal and semantic analogies - with biblical texts and with writings by T S Eliot, Ezra Pound and Sanguineti himself. The main formal reference of Laborintus II is the catalogue, understood in its medieval meaning (such as the Etymologies by Isidore of Seville, also present in this work). It relates to Dante's themes of memory, death and usury - that is the reduction of all things to a single monetary meter of value. Sometimes, isolated words and phrases must be considered as autonomous entities; at other times, instead, they must be listened to as part of the sound structure conceived as a whole.

The principle of the catalogue is not limited to the text, but also serves as the basis of the musical structure itself. In a certain respect, Laborintus II is a catalogue of references, attitudes and simple instrumental techniques; a catalogue with a didactic character, similar to the images of a school book that deals with Dante's visions and musical gesture. The instrumental parts are primarily an extension of the vocal music of the singers and the short sequence of electronic music is conceived as an extension of the instrumental action. The voices (a mezzo, two sopranos and chorus) become pure sound, while the narrator - here Federico Sanguineti - punctuates so that his every word is understood, but the verses pronounced by the singers must be followed by reading the libretto. We move from the 'recitar cantando' - acting while singing - to which in the Italian Renaissance, the first composers of musical theatre aspired, to the 'use of the voice as a musical instrument'. In the musical structure, there are references to madrigals, especially to the Monteverdi style.

Federico Sanguineti and the Bologna Conservatory Contemporary Music Ensemble performing Berio's Laborintus II. Photo © 2021 Andrea Caramelli and Federico Priori

Laborintus II can be performed as a stage work, as a story, an allegory, a documentary and as a dance. It can be played at school, in the theatre, on television, in the open air and in any other place that allows an audience to gather. In this production, it was shown as a mise en espace. Federico Sanguineti, in the costume of a wayfarer, was on the proscenium next to the conductor. Soloists and chorus members were under the large mural by Mario Sironi (which represents 'Italy between the arts and sciences' but can also be understood as a Dante allegory). The electronic console was in the corridor in the middle of the concert hall.

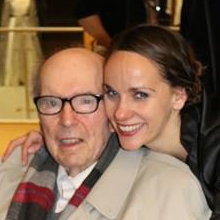

Marcello Panni, Federico Sanguineti and the Bologna Conservatory Contemporary Music Ensemble performing Berio's Laborintus II. Photo © 2021 Andrea Caramelli and Federico Priori

The large musical, vocal and live electronics ensemble gave a much better performance than that by the commercial CD edition of Ipecac 2012, based on a live (not studio) recording at a Dutch festival in 2010. There are two other recordings, now unavailable. Although the work is short (about forty minutes), Panni, the singers, ensemble and electronic keyboard showed very well that it is divided into three parts. (Like the three Canticles? Berio never mentioned it). In the first, the three female voices create a sense of mourning. In the second, orchestra and chorus embrace a crescendo full of discords while the narrator gradually raises the tone of his voice. In the third, there is a soothing musicality in which the winds dominate, counterpointed by percussion and echoes of jazz.

Laborintus II was preceded by two other pieces by Berio: Visage and his 1966 transcription of Monteverdi's Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda. Berio wrote that Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda 'can be considered one of Monteverdi's most experimental works, not only for its well-known rhythmic and instrumental discoveries but also for the conception of music and dramatic representation as a rapid, discontinuous and contrasted sequence of situations and attitudes'. In this production, the text of Tasso was sung by Chiara Osella, a mezzo who descends to alto registers. The stage action, namely the duel and death of Clorinda, was entrusted to two dancers, Liza Hofmann and Luzi Madrid Villanueva. There was great drama almost from Brechtian 'epic theater'.

Marcello Panni directing the performance of Berio's transcription of Monteverdi's Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda. Photo © 2021 Andrea Caramelli and Federico Priori

Visage (1961) is pure experimentalism on the use of the voice (in the specific case of Cathy Berberian) as a musical instrument to be paired with the electronic console. A single word is spoken twice: 'parole' (words). The vocal dimension is constantly amplified. It has a very close relationship with the sounds produced electronically. The program notes do not say that in Paris at IRCAM, Pierre Boulez considered it a classic. This was rendered very effectively at IUC with pitch darkness in the hall, and little lighting on stage, by Chiara Osella at the front and, under the mural, chorus members, who gradually disappeared, individually, leaving the stage from the right door.

Copyright © 14 November 2021

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy

MORE ARTICLES ABOUT THE ISTITUZIONE UNIVERSITARIA DEI CONCERTI