SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Well Realized - Varda Kotler and Israel Kastoriano - recommended by Geoff Pearce.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Well Realized - Varda Kotler and Israel Kastoriano - recommended by Geoff Pearce.

All sponsored features >>

Multiple Minds

The Concert Music of Mark Arnest: A Preliminary Investigation into the eclectic American composer, by GORDON ANDREW R

The philosopher and mystic George Gurdjieff suggested (and flew in the face of Western philosophy at least since Descartes) that humans are not a single person, but their minds are multiple. Each 'person' is actually many 'I's.

This is a very hard concept to grasp as it goes against our notions of individuality and personhood. The philosopher P D Ouspensky (a one time student of Gurdjieff) took up this idea and developed it in great detail and with considerable acumen. The American psychologist Robert Ornstein wrote a book entitled MultiMind, where he presents a related concept.

Actors, of course, do this all the time - they become different people in each role they play, and I mention that the great acting teacher Stanislavsky probably learned some things, like multiple 'I's from Gurdjieff directly. But, in absence of a personal centre, the process can be psychically destabilizing - which might explain why actors are often troubled souls.

In the modern world it is often required to play several different roles: worker, parent, spouse, hobbyist etc. and we can cope with that - though we do not often ascribe different personalities to the situations. But, I knew of one man who was a tyrant in his home life, and renowned at the office for being the jokester. But, he is the same man.

In the modern, eclectic world, different styles, manners, customs and social mores jostle us into confusion. Shall we eat Chinese, Indian, Japanese tonight? Watch Manga, Marvel blockbuster or French film noir? How do we properly greet a dignitary from Turkey, or First Nations? What spoon do we use first at dinner with the Queen? How do we address the Pope, a Member of Parliament, the Mayor of a City, a businessman or woman, the bank clerk or the plumber now in our home? It is a great jumble of issues, manners and behaviours, but we are not likely to call this the field of different personalities. That would be to wander in the realm of psychopathology.

But, in fact, these are all little symptoms of our minds not being one monolithic, single cast structure, but an amalgam, or a mashup of different parts.

Without wishing to belabour the point, I suggest this multiplicity shows up in creative lives, and also that some would vociferously disagree.

Some composers are adamant that there is one style, one way and that no others are possible. The recently deceased composer Charles Wuorinen was one such: fiercely dedicated to the twelve-tone system of writing, and it seemed that he could not accept, could not grasp and refused to countenance other composers doing other things.

When I was a student, you could choose your music composing style from one of two: Schoenberg or Stravinsky (of course, before he took up twelve-tone writing). There were three exceptions: if you were Hungarian, you were allowed to sound like Bartók. If French, then you could follow Messiaen. If you went to Yale, then you could imitate Hindemith. I suppose in England you were allowed to sound like whoever you wanted as long as it was Mendelssohn, the perfect English gentleman. I chose late Liszt and Busoni.

But, today, the lines are not so fiercely drawn nor fiercely defended. Oozing between the camps has occurred.

One reason for it is that professional life has become much more a series of gigs rather than an appointment to some Chair of Music, or department of a university or conservatory, and certainly not under the patronage of some kind of nobility.

Musicians need to earn money, they are offered opportunities and they must take them.

For composers it meant breaking away from some of their rigid thinking and training.

Certainly the boundaries have weakened. And they have weakened by the causes mentioned:

The need to gig;

The globalization of our experience;

The realization that 'style' is just another tool in the composer's toolkit.

This last was certainly practiced by William Albright and William Bolcom, both highly respected professors at the University of Michigan. Both wrote in varied styles and manners. Both wrote deeply serious, intensely complex concert music and also Rag Time. (Indeed, these two were instrumental in the rediscovery of that genre, which is now the common heritage of everyone.) Bolcom wrote piano etudes (winning him the Pulitzer Prize) that are playable only by super virtuosi, and also wrote rock music as part of his giant cantata/oratorio on the texts of William Blake.

Today then, the composer is expected, obliged and allowed to create music in a variety of styles, for many different circumstances, in a variety of manners, using a variety of techniques and for any number of purposes.

Mark Arnest is a modern American composer, pianist, scholar and researcher who has done just that.

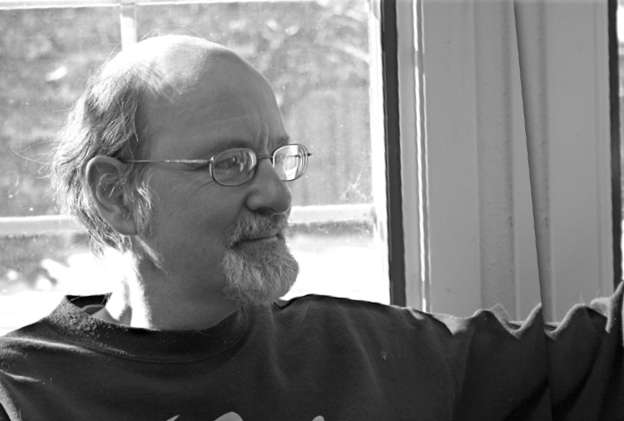

Mark Arnest

As an aside: He is one of the foremost authorities on late nineteenth century and early twentieth century piano performance practice as exhibited by the recorded heritage. I know only a few who might be his equal in this field, none his superior.

Thus, when considering his compositional creative output, one must consider:

- Theatrical scores

- Full Broadway style shows (written in collaboration with his wife, Lauren Arnest)

- Satirical music and novelty songs

- Intellectual music or music for study

- Choral music

- Concert music

These are broad categories, and a word is needed about each category, though entering into any greater detail would take us too far away from our purpose.

By Theatrical Scores I refer to music for plays. This was once called Incidental music, though now is often called sound design. Here are some of his works in this field:

- Eleemosynary

- Hamlet (play-within-a-play)

- Road to Mecca

- Pericles

- Wind in the Willows

- The Winter's Tale

- The Glass Menagerie

- Scrambled Shakespeare

- Our Town

- I Am Nicola Tesla

- The Seagull

- Everyman on the Bus

- It's a Wonderful Life

- Girl of the Golden West

Full Broadway style shows (often written in collaboration with his wife Lauren) include:

- All About Love, musical adaptation of Plato's Symposium, which was later released on CD in 1997

- Iron & Gold, a musical about 'nineteenth century robber barons, railroads, and labor' (1998)

- Pike's Dream, chamber opera (2007)

- The Notorious Nugget (2015)

For novelty songs, I can only suggest Devil in My Pants.

Listen — Mark Arnest: Devil in My Pants

(0:01-0:55) © Mark Arnest :

By intellectual music, I mean those works intended to demonstrate some aspect of musical technique - and also aiming for aesthetic beauty. The examples of this are versions of Pachelbel's famed Canon in these transformations.

Listen — Johann Pachelbel arranged by Mark Arnest: Canon (original and retrograde)

(0:00-0:58) © Mark Arnest :

Listen — Johann Pachelbel arranged by Mark Arnest: Canon

(upside-down and backwards)

(0:00-0:59) © Mark Arnest :

Listen — Johann Pachelbel arranged by Mark Arnest: Canon (backwards)

(0:00-1:00) © Mark Arnest :

Listen — Johann Pachelbel arranged by Mark Arnest: Canon (inverted)

(0:00-1:00) © Mark Arnest :

These are standard techniques of composition: original, inversion, retrograde and retrograde inversion, and have been used by composers for half a thousand years. Arnold Schoenberg made them part of his system of serial composition, but he was merely continuing a longstanding process. However, here, given the fame of the composition, it is as if one is taking some object and turning it this way and that in one's hands to see it from all different sides, angles and lights. The results are illuminating and Mr Arnest's contribution to our understanding of the music and these techniques is important and valuable.

Mr Arnest has also written choral music, of which this one stands as an excellent example. (The text is by Lauren Arnest.)

Listen — Mark Arnest: Winter (Solstice Carols)

(0:01-0:55) © Mark Arnest :

In a word, radiantly beautiful and coldly forlorn - as all winter is in truth.

It is, however, to this last category of concert music works that this article has tended. The list is long, so only two of the works shall be considered in detail.

- Prelude & Fugue for Piano (1974-75; Prelude mostly lost)

- String quartet, In Memoriam S J, for Da Vinci Quartet (1990-91 season)

- Wedding Fanfare for brass quintet

- Theme and Meditations, for chamber orchestra (2001)

- Towards the Garden (2009) for chamber orchestra

- Prelude for Diana for orchestra (premiered 2013, Colorado Springs Philharmonic)

- Ludlow: Four Scenes for Orchestra (2013) for chamber orchestra

- My Cousins' Cats for piano solo: Mai-Tai, Puff, Bonnie, etc (completed 2014)

- Panels for string quartet (2014) (commissioned by Green Box Arts Festival and Bee Vradenburg Foundation)

- Shout for 23 (2016), string instruments

Ludlow: Four Scenes for Orchestra

This multi-movement orchestral tone poem is inspired by the events of April 1914, when striking miners and their families were massacred by the Colorado National Guard and guards of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. I refer readers to these sources online for the historical background:

GREGORY DEHLER: LUDLOW MASSACRE

JONATHAN H REES: LUDLOW MASSACRE (COLORADO ENCYCLOPEDIA)

The four movements are:

1: Morning at the Camp

2: The Death Special

3: Fire

4: Elegy

Given the era of events chronicled, it is fitting that the music should be of a suitably homespun manner, tonal and melodically straightforward. This must be music for the American West, and there is a long tradition of just such music. Gestures, tropes, processes, forms, sounds and suggestions are all encompassed in that tradition (which appear quite frequently in Hollywood western film scores) as well as the more formal scores of 'Americana'-inspired works. One can think of the Eastern branch of Aaron Copland's Appalachian Spring, and the Eastern seaboard Charles Ives, but not the more rugged Carl Ruggles. One might also ponder the music of Virgil Thomson and Randall Thompson. It may be that the two quintessential examples of this genre are The Plow that Broke the Plains (film 1936, and suite recorded in 1946) by Virgil Thomson and the musical Oklahoma! by Rogers and Hammerstein on stage in 1943 and as film in 1955.

The first movement, setting the scene is given this description by the composer as it:

... represents the ethnic hodgepodge of the miners' camp with eleven folk songs from ten different nationalities: American (two songs), English, German Jewish, Greek, Italian, Macedonian, Mexican, Romanian, Russian and Westphalian. In honor of Louis Tikas, the strike's leader, the Greek tune initially heard on the clarinet often takes the lead. The folk songs gradually coalesce around the two main themes, which have been introduced in fragments.

Appearing already in this movement (and which grows through the other movements) is a sound quite special to Americana music: the trumpet solo, or the trumpet in long spun melodic expression. This was not always the task of the trumpet, as for instance it gives little more that severe punctuation in the symphonies of Beethoven. But, in the nineteenth century, the cornet took up long melodies, of a mellow and somewhat sweet nature. Though the cornet and trumpet have now seemingly merged - don't tell a cornet player that - the idea of the trumpet taking a lead melody has grown to epic proportions. The chief and best example is the John Williams melody for the film Raiders of the Lost Ark.

I would suggest that the cornet/trumpet represents in sound the philosophic, cultural and mythic ideal of the rugged, solitary and self reliant individualism that haunts the American mind and soul. It has now turned self-destructive as an ideal of a non-existent past to which we must return: 'Praise god and pass the ammunition'. Notice that this presumably solitary notion claims to have some god on its side, and evidently someone else to assist in loading the weapons. For the solo trumpet, let it be known that it rarely truly plays alone, just as no human, be he (and it is almost always a 'he') Emersonian American, John Wayne wanna-be, or Clint Eastwood simulacrum can survive utterly alone.

And so, in this work, the trumpet adds its individualistic tone to the struggle for the rights of the many in the face of the insensitive rich. And this struggle is complex and confused. Arnest himself has added the melodies mentioned above, and there are moments when the tonal soundscape here almost reaches the level of a Charles Ives sonic phantasmagoria. The question always becomes: how do you hear the voice of the individual within the mass? This tone poem is the struggle of the individual, but subsumed in the mass, and eventually destroyed 'en masse' by brutal criminals who eventually escape scot-free. This seems to be the American way.

The suite of tone-poems also raises questions of story-telling in music: can music tell a story, can music be about telling stories, can music only provide moodscapes for some other activity (say a film, narration, opera), or is there some latent power in music to drive, cajole or inspire our thoughts along certain lines of thought and emotion? As mentioned above there are musical tropes that might be sign posts for where we are and what sort of things we might be thinking. However, music is phenomenally powerful in creating a mood. This was recently mentioned:

DreamWalkers, Idries Shah's 1970 documentary for the BBC, contains a brief scene repeated with different music and totally different effect. (Warning: This is not for the faint of heart!) Start at 6:46 for a one sentence explanation of what is to follow. I find it horrifying to watch one of the versions. But, such is the power of music and our expectations based on consciously ignored stimuli. - Life Under Quarantine, Gordon Andrew R, 17 May 2020 update

In the nineteenth century Franz Liszt proposed a more thoroughgoing conception of programme music, created the musical form of the symphonic poem, which eventually influenced hundreds of composers, but, also went on to degenerate into musical accompaniment to silent films. I do not believe that Liszt foresaw his music being the mere background noise to a Hollywood blockbuster (from 1935 or 2020). The danger of programme music is great in that music ceases to be the fundamental matter and becomes the mere servant of some other art form, even if that is the story being told by the listener in the privacy of his own mind.

The second movement is frightening and horrifying. It is hard to imagine the evil that would have gone into creating and using this machine described by Mark Arnest so simply:

The Death Special was the strikers' nickname for an improvised armored car, mounted with a machine gun, that the mine-owners' detective agency used to harass the strikers.

The oboe barks a vicious tune, while the strings take up a theme that can only represent the victims. According to the composer:

The continuously repeating nine-and-a-half-beat rhythmic ostinato spells 'death' in Morse code.

The trumpets take up the tune, and I suggest it is the evil side of the Wild West mentality that obsesses the trumpet - besides, this manner of harsh melody can easily suit the trumpets nastier nature.

A fearsome climax where machine of death and miners' resistance collapse into a brutal, angry and vehement sonority.

The movement 'Fire':

... depicts the climactic event of the assault on the camp: The fire in which two women and eleven children suffocated. The 'death' rhythm reappears at the climax, where the first movement folksongs are devoured by the flames.

There are flashes of synthetic scales and a grinding bitonal sonority that combines a C sharp minor chord with a D minor chord that pauses the rushing flames, and I take this to mean the shock and frozen panic of the victims. It is frightening music and I prefer to further remain silent out of respect for the dead.

The composer laments:

The finale is an outpouring of grief that never leaves D minor and ends with a choked echo of the first movement.

A forlorn melody of modal design played upon the English Horn (a most forlorn instrument) with enough pentatonic character to make it American, and is repeated, re- orchestrated and re-harmonized. The melody is responded to by a bleak and emotionally blank string interlude (usually just on the single pitch D, with varied orchestrations), that acts as a frozen ritornello.

How then does the music go on, develop, continue, have anything more to say after this? Early on the clarinets interpolate a new motif into the theme, which for some reason reminds me of a device of Liszt. The effect is beautiful and allows us to understand that the melody will grow and alter, but never lose its real nature, even though it will be interrupted by that emotional abyss.

The culmination of this process is a three part motet (!) that reminds me of Johannes Ockeghem, the fifteenth century composer, and glows with gorgeous and radiant counterpoint. I vaguely recall a Rabbi say that 'This is the worst of all possible worlds in which there is still hope.' This passage represents that frail and feeble expectation.

Thereafter, the strings take up fragments of the theme (and indeed do move slightly away from mere D minor, with the occasional flat second harmony), and at a climactic moment the trumpet adds its voice to the upward reaching motif, and then the solo trumpet takes over in a highly decorated and elaborate version of the melody. The individual - the lone voice, the quintessential American voice - speaks over and above all, the melody rising in powerful harmonic steps of despair and in cries to an unheeding heaven.

After a grand climax and emotional collapse that is finely handled, the music falls away very effectively, the same melody returns at the end as was at the beginning of this movement. And if I may offer a philosophic observation this implies to me the cyclic return of suffering and affliction in a Universe that simply repeats endlessly the same torrents of pain.

My Cousins' Cats for piano solo

I sometimes wonder what motivates composers to write about cats. When I received Mark Arnest's work, I also received one from the Australian composer Michael Kieran Harvey. I'm 'so-so' on cats and am less inclined to treat them as inspired and poetical manifestations of the sublime (as perhaps the ancient Egyptians did). But, still one must turn to the music, and here I think less of cats than Siberian tigers. There is a great deal of vigour, power and a deep and dangerous growling in these works.

Commissioned by a cousin who requests anonymity, this set of four pieces is divided into two based on geographic inhabitation:

The Hawaii Cats:

1. Bonnie

2. MaiTai

The Boulder Cats:

3. Puff

4. Tino

The composer is quite keen on the character of the cats, and provides this important information:

Bonnie is a miniature Pictures at an Exhibition - or perhaps Pictures of an Exhibitionist? - as she appears as lover, mother, and hunter between short framing sections. Mai Tai would like to keep cool - but what's happening at the refrigerator? Like Bonnie, Puff is a prodigious hunter, but with a darker attitude. Tino is all acrobatics and fun.

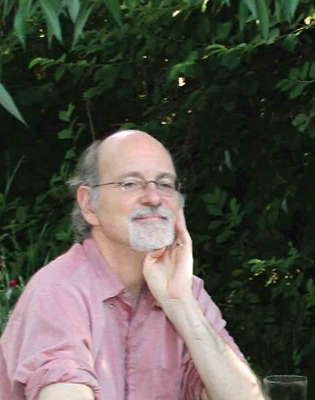

Mark Arnest

Also significant for the overall set is this observation by the composer:

In keeping with its playful nature, the suite abounds in quotations. Some are obvious, others less so; but I hope that all - whether it's the Norwegian national anthem, the Dies Irae, the theme from Hawaii Five-O, Ravel's Scarbo or one of the others - are integrated into the musical vocabulary.

Bonnie begins with a brief introduction using a species of (symmetrical) inversion, thereafter, the main theme begins 'Amorously' and is based on two tiny ideas, a minor second and a brief scalar passage. Each undergoes, extension, transformation, addition and subtraction to create the larger phrases. (Let that be enough of the grammar of the musical contents). The result is a tightly constructed, and directionalized movement that alters between a two part invention, and rushing and swirling passage work. Synthetic scales abound, which result in a kind of mid-20th century harmony - not serial, but not old fashioned harmony.

I leave to others to identify the theme that captivates Mai Tai in the 'jazzy' second movement. It will be obvious to some, and to others suggests some flickering remembrance. But, is that also not a tool of the creator? To use some idea that causes just a flicker of awareness, and not an outright shock. Besides, the sensation of familiarity is a real aesthetic sensation and is here used most cleverly. No further spoilers.

Puff is perhaps the most traditional of all the movements. It stays closest to traditional harmony, with its moves and its gestures. Consider it tonal, but with many added notes. The second theme (at bar 13) could almost be sung by a choir, would have intrigued Brahms and certainly would have pleased Randall Thompson.

The middle section is based on a single bar long rhythmic/melodic and accompaniment motif repeated through changing harmonic movement. But, it is not minimalism because of the directional harmony. A great climax is reached using this one bar, and if one is careful, at the uppermost limit of tension, one hears the grand lament theme of the Catholic Church sliding downwards in a slithering Fall until it creaks, cracks and fractures into tiny shards.

Tino (of the last movement) was born and bred on the same farm that raised Prokofiev's late Sonatas. Harsh (but not vicious) chords, sudden swishes, rushing cascades, and hard repetitive, but harmonically inert brutalistic chords beat upon ones ears. The great Soviet pianist Emil Gilels would have played this well (and like all these pieces these are for the virtuosi alone). A fugato (or is it really a fugue?) rattles its sabre at us in a grim Beethoven fashion with inversions galore, compressions abounding, gradually tightening and eventual expanding to great reaches for the pianists hands and arms. But, like Prokofiev, the climax steps back from the brink and does not overwhelm. A return to the brutalistic rhythm, flourishes and cascades now grown to a veritable water fountain garden (like the Grand Cascade at the Peterhof Palace in St Petersburg) until every device of pianist fervour is used at the limit of the pianist's stretch of hand and reach of arm.

Copyright © 3 September 2020

Gordon Andrew R,

Canada