- Eastbourne

- Jacques Charpentier

- Alice McVeigh

- Aaron Copland

- Donna Anna

- Canadian

- Piers Adams

- Benjamin Jaber

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Melting Rhapsody - Malcolm Miller enjoys Jack Liebeck and Danny Driver's 'Hebrew Melody' recital, plus a recital by David Aaron Carpenter.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Melting Rhapsody - Malcolm Miller enjoys Jack Liebeck and Danny Driver's 'Hebrew Melody' recital, plus a recital by David Aaron Carpenter.

All sponsored features >>

Wagner's Revenge

GIUSEPPE PENNISI is puzzled by a political and contemporary reading of 'Parsifal'

On 26 January, the grand opening of the 2020 season at the Teatro Massimo in Palermo had been sold out for several weeks. Many dignitaries were in the theatre. The start of the show was at 5.30pm, ending at almost 11pm, after fifteen minutes of roaring applause, with some shy reserve from the upper tier. I was in an orchestra seat. It was only the third time that Wagner's Parsifal had been staged in Palermo. In Italy, it is rarely programmed given the great productive commitment it entails. The staging in Palermo is a co-production with the Teatro Comunale of Bologna, where it will be performed next season. In Bologna, I remember two excellent productions of Parsifal in 1980 and 2014, although very different from each other.

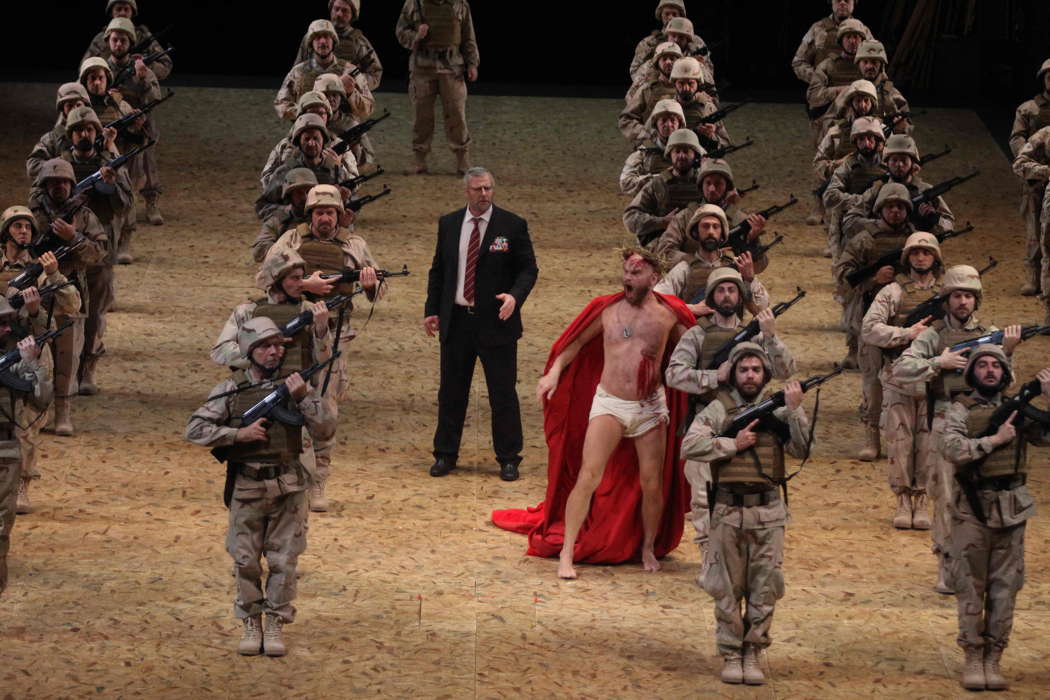

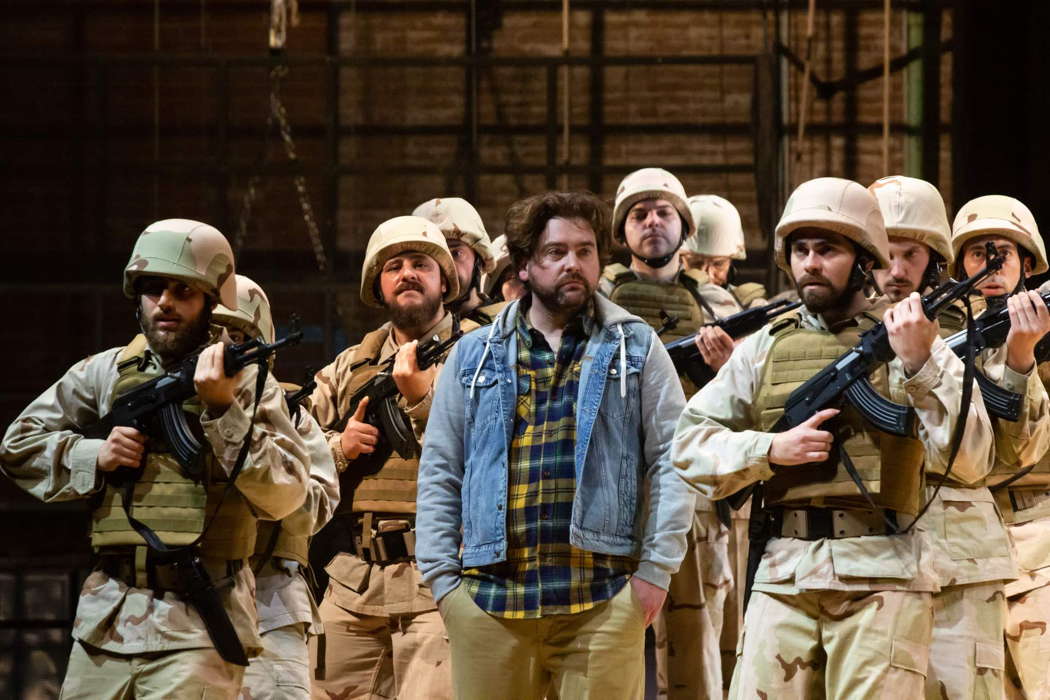

I want to distinguish two aspects of Parsifal as seen and heard in Palermo: dramaturgical and musical. The creative drama team consists of Graham Vick (director), Timothy O'Brien (scenes), Marco Tinti (costumes), Ron Howell (mimic actions) and Giuseppe Di Iorio (lighting). I must admit that the stage direction and set-up was applauded by the audience and by most of the critics too. In my opinion, Wagner's latest masterpiece, called by the author Ein Behnenweihfestpiel, translated as 'mystic drama' or 'sacred drama', is eminently religious and transcendental. So, a-historic. The creative team, on the other hand, desacralized it and placed it in the Middle East today. The Grail is no longer the cup in which Joseph of Arimathea preserved the blood of Christ, but is all of us if we work for universal peace. In the final scene, after 'the purification of Amfortas', there is a great embrace between Americans, Israelis, Scythians, Sunnis as well as a crowd of children - the future generations that will, hopefully, live in peace. This is a very political and contemporary reading.

A scene from Wagner's Parsifal at Teatro Massimo di Palermo.

Photo © 2020 Franco Lannino

In my opinion, this reading of Parsifal has little to do with the spirit of the opera on which Wagner worked for over twenty years. In other productions in recent years, Parsifal has been Buddhist, pantheistic, secular and non-Christian, but transcendence always remained at its center. The stage action was conducted with great expertise, as befits a creative team of such a high level. However, I was puzzled throughout the show and did not find the subsequent conversations with colleagues convincing.

I think that Parsifal is one of the most overtly Christian works of a seventy-year-old Wagner who has dealt with the struggle between Good and Evil since his first works. In Parsifal we are in the heart of the world of the Grail - the cup where the blood of Christ was collected on the Cross, revered and protected by an order of pure knights. Sin is lurking more than ever. Kundry, a beautiful and always young woman, laughed in Christ's face on Golgotha and was 'condemned not to die' until she was 'redeemed'. Klingsor castrated himself because he could not resist the carnal temptation. He has wounded the heir to the Kingdom of the Grail, Amfortas, with sores that progressively prevent him from celebrating the Eucharistic service. The curse can only be won by a 'pure fool' such as the innocent and wild Parsifal. He needs a long initiation to 'become wise through piety' and understand the mystery of the Eucharist service, destroy Klingsor's castle, purify Kundry (and allow her to die peacefully) and Amfortas, taking its place both in the celebration of the Eucharist service and in the guide of the Kingdom of the Grail. The conclusion, however, is 'open', a strong sign of belonging to Western culture: the Knights of the Grail, their pages, the protagonists and a voice of the high call for 'Erlösung dem Erlöser'! (Redemption to the Redeemer!), a vision according to which the Redeemer himself must be continuously redeemed by humanity.

Finally, in Parsifal, the contrast between the pagan world of sin and the Christian world of purification and redemption is accentuated because, musically, the world of the Grail is as diatonic as that of Die Meistersinger, while that of Klingsor and Kundry (in the first two acts) is as chromatic as in Tristan und Isolde. Reducing this to the conflict in the Middle East and its eventual appeasement is trivial, as well as reductive.

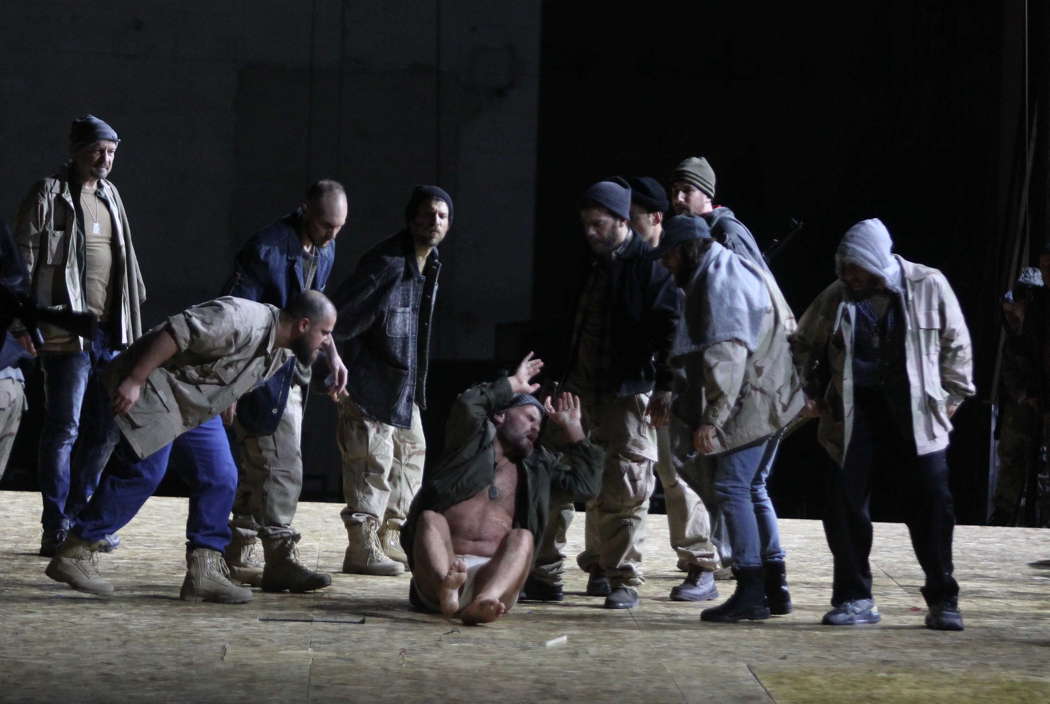

A scene from Wagner's Parsifal at Teatro Massimo di Palermo.

Photo © 2020 Franco Lannino

Nonetheless, Wagner always takes revenge on those who misrepresent him. The production features a magnificent musical performance led by Teatro Massimo's new music director, Omer Meir Wellber. Meir Wellber and the Massimo orchestra (which has the advantage, compared to those of other opera houses, of having a symphonic season with important guest directors) offers a philological reading, free from the encrustations and changes of tradition accumulated over the years. One aspect that may seem pedantic should be emphasized: there are bureaucratic diaries of the 1882 representations in Bayreuth under the watchful eyes of Wagner and of Hermann Levi, the conductor; these diaries determine the times - one hour and forty-five minutes for the first act, one hour and five minutes for the second, and one hour and ten for the third. Today, there are very few conductors who follow these directions: Levine, Kuhn, Thiellman and a few others. With Toscanini - as is well known - Parsifal's first act lasted two hours and twenty minutes. With Boulez just over an hour and a half. Omer Meir Wellber and the orchestra strictly respect the times set by Wagner and Levi. They also show the differentiation between the 'diatonic world' and the 'chromatic world'. The performance reminded me of the famous stereophonic studio recording led by Georg Solti in the mid-1970s. And it is no small feat. The chorus led by Ciro Visco was excellent.

A scene from Wagner's Parsifal at Teatro Massimo di Palermo.

Photo © 2020 Rosellina Garbo

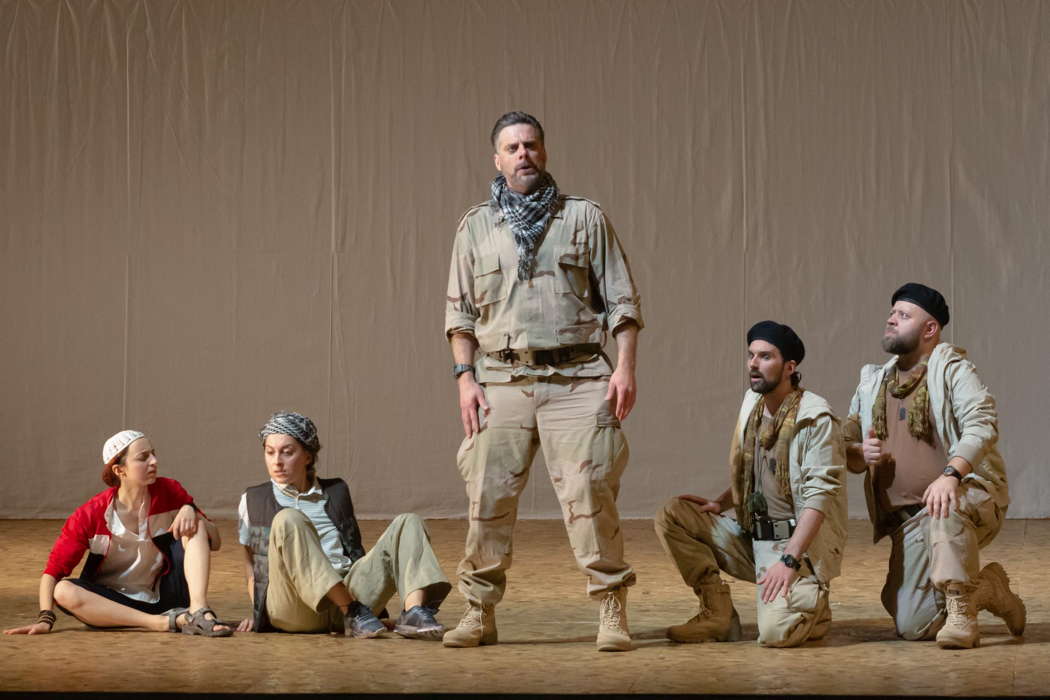

The vocal cast is of a high level, starting with John Relyea in the tiring and long role of Gurmenanz.

John Relyea as Gurnemanz (centre) in Wagner's Parsifal at Teatro Massimo di Palermo.

Photo © 2020 Rosellina Garbo

Amfortas by Tómas Tómasson and Klingsor by Thomas Gazheli were great.

Tómas Tómasson as Amfortas (centre) in Wagner's Parsifal at Teatro Massimo di Palermo.

Photo © 2020 Franco Lannino

I would have preferred a darker voice (and a more seductive look) for Kundry than those of Catherine Hunold.

Catherine Hunold as Kundry in Wagner's Parsifal at Teatro Massimo di Palermo.

Photo © 2020 Rosellina Garbo

This Parsifal production's coup de théâtre is the tenor who debuts in the title role: the young Julian Hubbard.

Julian Hubbard in the title role of Wagner's Parsifal at Teatro Massimo di Palermo.

Photo © 2020 Rosellina Garbo

He was hired as a cover, that is, a substitute available in case the principal could not sing, but had to face the opening night (and all the other performances), showing great acting and vocal skills, especially in very difficult pieces like Amfortas! Die Wunde! Die Wunde! and Nur eine Waffe taugt.

Copyright © 29 January 2020

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy

FURTHER INFORMATION: RICHARD WAGNER