SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fascinating Recording - John Joubert's string quartets, heard by Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fascinating Recording - John Joubert's string quartets, heard by Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

Only the Screen

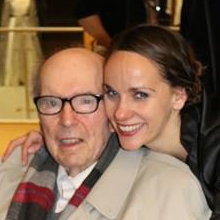

ONA JARMALAVIČIŪTĖ talks to the

Belgian singer and conductor Tore Tom Denys

On stage, we artists are only the screen, on which the images must be created by the listeners themselves. - Tore Tom Denys

Tore Tom Denys (born Roeselare, Belgium, 1973) is a singer (tenor), co-founder of the Renaissance ensemble Cinquecento, founder of the Baroque music ensemble vivante and an incredibly creative personality, testing his strengths in such creative spheres as conducting, video art, acting and producing. His career started after he obtained a master's degree in trumpet playing, only then discovering that singing was his true path. He worked with Vienna's State Opera choir and was a performer at the Salzburg Festival for six years. This summer, he returned to the festival, now as a soloist, to perform his Renaissance music repertoire. Before this, I met with the singer to talk about his career path, work routines and creative aspirations.

Tore Tom Denys

Ona Jarmalavičiūtė: You are an extremely creative personality, known as a singer, conductor, producer, etc. How do all these different experiences help you to express yourself?

Tore Tom Denys: It is important to me that every activity boosts my creativity and allows me to express myself. When I meet other creative people, I want to collaborate with them right away. Of course, in this world, you need to make money for survival, but money is not my primary concern and I am happy to participate in projects where nothing is paid ... especially when they excite something in my mind. Then I have to work on it - there is no other way. Sometimes, if you are lucky, maybe it becomes the beginning of something bigger, then you can continue working on that project and sell it later. It is important to me that every creative project I work on excites me. But these things are always spontaneous. I am not an artist who is sitting at home, waiting till the opera house calls me to offer me a job. I have colleagues who have performed and still are performing Tamino without getting bored or tired by this experience. Such a career path is not for me. I participated in several operas, but they were composed by modern artists. A few years ago, at the Salzburger Festspiele, I took part in the performance of Luciano Berio's Cronaca del Luogo. At that time he was still alive and came to listen to rehearsals. I was extremely interested in seeing the creative process. Also, yesterday I was at the Wiener Festwochen Festival and saw Hungarian director Béla Tarr's movie Missing People. The film lasted two hours, though it felt like only thirty minutes. A very slow motion movie, but very creative ... Every such experience inspires me, and I also try to stay creative.

OJ: You have changed your career. Is it true that originally you were going to become a trumpet player?

TTD: I have a single diploma - a master's degree in trumpet playing. However, I have always felt that this is not exactly what I would like to do professionally. A trumpet player in his profession, like every instrumentalist, looks for a good quality sound. And yet it is a humbling profession that requires hard work. I used to practice every day for five to six hours - whether it's Christmas or Easter, or a weekend. There was no rest. And the job is lonely. So I always wanted to look for other ways I could express myself. My girlfriend at the time was a singer and she persuaded me to take part in a singing audition. She said I had the right voice and she could help me to get ready for it. After a few weeks of rehearsing, I performed the aria 'Maria' from West Side Story. Now, even when I remember, I can't imagine how I sounded at that time [laughs], but they accepted me. It was the World Youth Choir, a project of Jeunesses musicales, where you can travel and perform around the world, and the choir pays for your travel expenses. The rehearsals took place for two weeks and the choir went on tour for the next two weeks. This way I visited so many countries. I had never had previous experience of singing in a choir, and I really enjoyed this way of living.

After returning to Belgium, I immediately started looking for new opportunities to sing. So suddenly my life turned upside down and I became involved in this new world of opera and singing. At that point I decided to try to become a professional vocalist. I also wanted to leave the country, so I was looking for a new place for my vocal studies. I considered lots of places, but finally I chose Vienna because, compared to other cities, it turned out to be the cheapest. In the beginning, I expected to go to Vienna for only three days - to take part in the audition and go back home. But now I've been living here for twenty years. Of course, I was lucky because as a singer I had no lectures such as solfeggio or counterpoint. I only attended singing, Italian and diction lessons. It was perfect for me. However, after a couple of years, I found a private singing teacher and ended my class studies. I worked in the Arnold Schoenberg Choir for six years. After that I did an audition for the choir of the Vienna State Opera Theater and was a member for five years. Then I left this work because being a small part of a choir didn't allow me to express myself creatively. There is no artistic satisfaction when you are the thirteenth tenor from the left and the overall sound does not change if you sing louder, quieter or in a more beautiful manner. In this way I learned another new thing about myself - I didn't like working in big groups. It wasn't enough for me to perform the compositions - I had a lot of questions and wanted to stay creative.

So after five years of working in the opera theater, I decided to look for other ways to express myself through music - through singing. I started performing ancient music professionally. My colleagues in Belgium consistently offered me new opportunities and I finally chose to stay and work with the vocal quartet called Capilla Flamenca. The ensemble itself existed for 20-25 years, and I had a good decade in it. It was my first stable job as a tenor. With this ensemble, we had sixty concerts a year, and we performed in many countries. It was like being a part of a string quartet, only vocal. However, five years ago, the quartet's bass singer, who was the ensemble's leader and founder, died. Since then the quartet has not performed, and I have been doing different things. I am currently focusing my energy on vivante and Cinquecento.

vivante

OJ: When you began your career as an opera soloist, how did you imagine your future, and what were your expectations?

TTD: I don't think I had any expectations when changing my profession. This situation was somehow a coincidence, and compared to the trumpeter's path, it was a completely different situation. I started playing trumpet when I was eight, and at that age, I really didn't know what I wanted to do professionally. At that time my town's orchestra lacked trumpet players. I dreamed of playing the soprano saxophone, but there was a demand for trumpet players in the local band, so I became one. I didn't really understand what was happening at that time. I think that at this age you just did what was people wanted you to do without thinking much about it. I played, practiced, and mastered the instrument.

A completely different situation occurs when you are twenty-four. By this time you can make a decision to become a singer. This desire arises more from the heart. You know what you want, and you can imagine the result that you want, but the problem is that there is a lack of technique to achieve that. For me, this change and the conscious choice of profession was a very important step. And every move towards this career - every audition, every concert is special to me. I had a lot of opportunities to sing in different churches and locations in Vienna. I went all the way without jumping the steps. I am very grateful for this trip and all the experiences. It was consistent, calm and allowed me to learn a lot.

OJ: What were your first impressions on your arrival in Vienna? What image did you create about this city?

TTD: My first impression was, of course, very positive. Because there is an extremely strong tradition of classical music. The Belgian music culture was not as sophisticated as here. In Vienna many churches have their own choir and soloists. There are masses played and sung every Sunday. Such things made a big impression on me. When I was still studying singing, I was involved in various auditions in all of these churches. Already at that time, I was very interested in the Renaissance music tradition, but I was surprised to see that the composers of this ancient music, who composed here, were completely forgotten today, and that their music was not performed. For this reason, I founded one of the ensembles, Cinquecento, to raise the awareness of traditions of Renaissance and Baroque music and to allow an audience to enjoy these undiscovered treasures of art. Everyone here performs the same thing again and again - Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, etc. And the previous composers are completely forgotten. Although none of these composers' creations are a part of the repertoire of today's concerts, the National Library is filled with manuscripts that were left here in Austria during the Renaissance and Baroque epochs. Numerous works of wonderful music - all forgotten. So there are inexhaustible options for repertoire selection. My main job here is to find these creations and bring this forgotten past music to the scene of today.

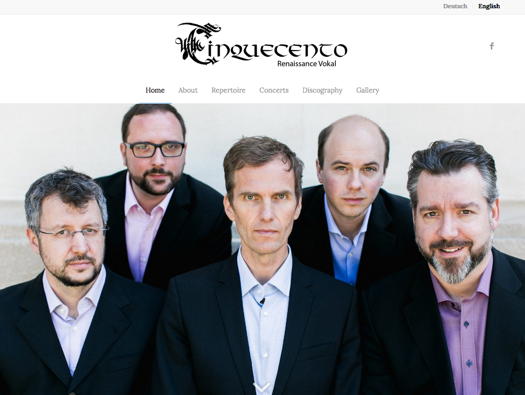

Cinquecento Renaissance Vokal. Photo © 2017 Theresa Pewal

OJ: Which achievement are you proudest of in your career?

TTD: I am happy that I never feel like i am 'working' in my professional life. Of course, I am busy, I have a lot of projects, but I am happy and enthusiastic about all of them. I don't have to go daily to a particular job to spend eight hours there. In this way I am responsible for my own time. Of course, there are always things in life that are hard or unpleasant, but in the end, I don't feel like singing is my 'work' or 'profession'. I prefer to call it a 'vocation'.

OJ: How do you choose your repertoire? Do you have the complete freedom to pick what you want?

TTD: If you work in an ensemble performing Renaissance music, you partly depend on early music festivals taking place in Europe. Organizers might ask you to perform a program from a CD that we already released. Alternatively the festival has a theme and asks for a new program that would fit. The second option is more complex, but sometimes such challenges are needed. A festival might commission an unheard topic from you, you offer something, they reject it, and then you have to go looking for better material. Sometimes the repertoire offered is rejected several times, but more new compositions are discovered during this process.

It is much easier when festival organizers are listening to the ensemble's CD and ask to perform the programm from it. In this case, we need one day for a 'freshing-up' rehearsal and the next day we can perform it. For example, we recently recorded a new album with vivante in which we perform Monteverdi's seventh book of Madrigals. In fact, this is standard repertoire, but is not often performed as a whole, because the Madrigals are almost all written for two tenors and a continuo group. So I hope that we will be able to perform this repertoire a lot of times in the near future!

OJ: How do you choose which tracks you would like to record on CD?

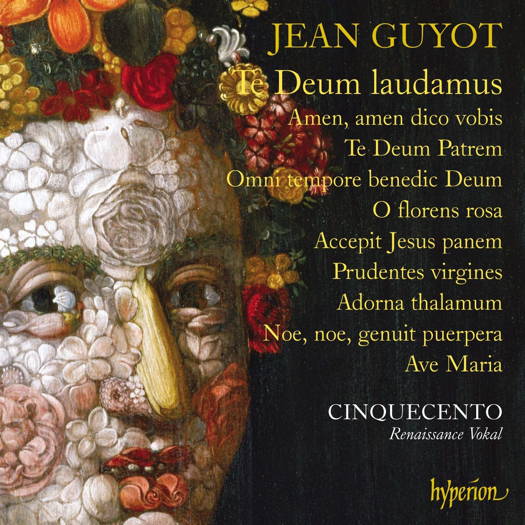

TTD: Cinquecento, one of my ensembles, collaborates with a British label for which we only perform music that never has been recorded before. So we always have new suggestions and compositions. It usually takes a lot of time and energy to go to the library, rewrite and edit manuscripts, interpret and rehearse. A lot of work, but in my opinion it is very meaningful.

Jean Guyot: Te Deum laudamus. Cinquecento. © 2017 Hyperion Records

OJ: When you are on stage and performing music, what is your intent? What do you want to convey to your listeners? What impact do you want to have on people buying your CDs and visiting your concerts?

TTD: Influence is not something that can be imposed on another person artificially. In my opinion, as a performer, I am just a person who brings the listener to music. I'm not important, people come to listen to the music, not to me. In Cinquecento we constantly say that we are like a door which listeners must open themselves. We give the listener the opportunity to experience a musical adventure, but the adventure itself is music and its sound. In addition, we perform Renaissance music, which also has a different purpose in itself. Most of our repertoire is religious music. Of course, not chansons or madrigals, but for example the motets or masses. Such music is contemplative, and listeners are often in their thoughts, content with their inner experiences while listening to early music. Whether it's related to religiosity, prayer, or not - doesn't matter. When I perform, I often notice that audience members are listening with their eyes closed. I don't think they start falling asleep - I think they are trying to get a better experience. On stage, we artists are only the screen, on which the images must be created by the listeners themselves.

Of course, as this is music to be performed in church, it is perhaps not entirely appropriate to carry it to concert halls. I think that is the case, for example, when a Requiem Mass is performed outside of the church. Then you have to try to create an atmosphere where people can really get into the music, without having the acoustics of a church. Unfortunately the performer doesn't always have an influence on the decisions about where the performance is going to take place ...

OJ: How did you discover yourself as a creator in other fields of art?

TTD: I recently started experimenting with video art and creating some clips for my music. In 2017, I performed Monteverdi's song 'Si dolce è il tormento' - how sweet is suffering - and I always had a picture of a crying person in mind. So I decided to turn this vision into reality. I invited a friend who did performances and asked if she would agree to cooperate. It was a difficult task because I needed a person who would cry in front of camera for quite a long time and it was supposed to be a natural expression of pain. The girl who agreed to perform it had a very interesting, expressive face. Indeed it was a long process until we managed to record that clip. However, the result was great, that is exactly what I wanted, namely what I had in mind. For the first time, I felt that I was giving the world the interpretation that defines what I want to express as a creator. You can't always do that. Still, visual arts attract me. I have also made another video on John Dowland's 'Come heavy sleep'. That's how experiments take place. I intend to create more in this area in the future.

OJ: How does your work routine look? Do you have any daily rituals?

TTD: I try to do sports several times a week, to avoid the back problems I had in the past coming back. I have singing lessons to this day, every week or every two weeks. My singing teacher is almost eighty years old, but he has been working at the Vienna State Opera for half of his life, so he has a lot of experience and knowledge. And there are a great number of singers among this teacher's students who are still working at Vienna State Opera today. I think that whatever your profession is, it is important to never stop learning and growing. Perhaps this could be called the ritual of my professional life - never stop practicing or looking for new opportunities for expression in music. It is always a good idea to deepen your professional knowledge and this growth process is extremely important to me. I stopped working for the opera in 2005. If I was still working there, maybe I would earn more, but I wouldn't be happy. I am an artist, not a banker. Creative self-expression is more important to me than financial stability.

Tore Tom Denys

OJ: Your working tool is your voice. How do you take care of it, keep it safe?

TTD: In fact, when I used to play the trumpet, I was surrounded by other trumpet players. They all smoke, drink and maintain a very unhealthy lifestyle. I experienced a dazzling shock when I suddenly found myself amongst other singers, where everyone was extremely concerned about their voices. Until now, I can't say that I am paranoid about my voice. I do not smoke, but I also take care of my voice in the same way every person does, not just opera soloists. For example, if the temperature outside is 25 degrees Celsius, and the inside is powerfully air-conditioned and the temperature drops to 15 degrees, then I will put something on my neck to prevent sickness. But I really won't run around with a scarf in the middle of summer just to protect my vocal chords.

OJ: How do you create your own musical interpretations? How do they differ when talking about modern, classical and ancient vocal music and its interpretation traditions?

TTD: In my opinion, the most important thing in creating an interpretation is to understand the language in which the composer writes. I usually hear that I have to understand what the composer wanted to say with this piece of work, which is true, but for full understanding, this also has to include other components. For instance, I try to feel the form and structure of the piece. When I perform Monteverdi's recitatives, I always have the feeling that he is writing out notes to create a truly realistic simulation of speaking. In reciting you can really feel the word, its structure, and meaning. Continuous rhythm and melody are adapted to the sentences and phrases, with the aim of expressing them as clearly as possible.

Often, vocalists use the metaphor of 'building a cathedral of sound'. However, if a composer of the Renaissance writes music based on the texts of Petrarca or Dante, it is quite necessary to pay attention to this. Composers know what they are doing, they try to express the words with sound, not the other way around. The text is extremely important to me. The composers of that time were really aware of this. It is often thought that the further we go back through music history, the simpler the music we find. This is not true. Composers then were extremely educated and knowledgeable in all seven of the free arts - mathematics, music, dialectic, astrology, etc. Nowadays, we do not find such interdisciplinary people anymore, unfortunately. So, in order to understand this kind of music, you really need to know a lot. When I try to create an interpretation I have to be interested in that time, and in a sense, become a musicologist and historian. Also, I have to put in a lot of effort and work until I can start singing ancient music and thinking about interpreting it.

OJ: Does the whole process usually begin with the transcription of the musical notes?

TTD: Yes, this is usually the case. Often, transcripts of notes of old music works can be found on the internet, presented in modern notation. Often those transcripts are bad or not useful for performing. Most of the time I transcribe the original, written in mensural notation, into a modern edition.

OJ: How does the process of music interpretation go in the ensemble? By what principles do you make decisions?

TTD: Well, the situation still depends on whether we work with a conductor or not. In the first case, musicians usually know that they do what the conductor says because that's what they been paid for. So everything is easier then. And when there is no conductor, we have six musicians and no leader in the ensemble - full democracy prevails and we often hear five to six different opinions on the issue of interpretation. Then it is much more difficult to make decisions and move forward in the creative process. We have been together with Cinquecento for fourteen years and with vivante for twenty years - with the same people. So, together, we have experienced a lot of disagreements, problems, and even crises. But we always got out of them. Even when we were in a crisis and had huge disagreements with each other, we always continued our work and moved on. I think this is the essence of creative cooperation. We are a team, and we have to work together, despite our own personal failure. Otherwise, I would have to sing canon arias in the opera halls. I like my job, with all of its challenges. And compromises have to be made by every member every day. This is the cost of collaboration.

The website for Cinquecento - Renaissance Vokal - www.ensemblecinquecento.com

OJ: I want to inquire about the Salzburger Festspiele, to which you are invited to return this summer. What memories do you have of the last time you participated in this festival? What do you expect this year?

TTD: For me, Salzburger Festspiele was like a sort of musical paradise. At that time I worked at the Vienna State Opera and in the summer the season closed and the whole choir moved to perform in Salzburg. We sang a lot of modern music - Schoenberg, Berio compositions. Every summer I participated in four or five operas on average. The schedule was impressive - in the morning you rehearse along with Sarah Brightman, for example, and in the afternoon, Thomas Hampson. The soloists are world-class stars - it's a great pleasure to perform with them. I remember when we staged a modern opera about Goya, and the main role was then sung by Plácido Domingo. Before the rehearsals, I was convinced that he would arrive as a soloist in the last few days, perform an opera and leave, saving his time. It wasn't the case - Domingo spent all five weeks with us and we saw him in rehearsals every day. For me, this was something special. On some days he saved his voice, but he did rehearse and prepare for this performance quite intensely. Most of the singers asked to make an audition for him, and he spent some time listening to all the singers and giving them advice. I didn't expect that from him. Of course, the great masters do not always behave in this way. Usually, stars need attention, but the world's most famous musicians, the brightest stars - do not need anything. There is no sense of their ego - it's just music. It was extremely nice to see that Domingo was a simple, down to earth man. Another personality that has left me with an indelible impression is conductor Claudio Abbado. I have such great respect for him. I remember when we performed Mahler's second symphony with the choir with him, it was an incredible experience. The entire choir and the orchestra rose from their chairs by a few centimetres. So my experience in Salzburg is really fantastic.

For such things, my professional life reminds me of a journey rather than a job. Traveling and experiencing new impulses, testing new things, from one step to another. And now I feel like I've done a full circle in my career as I return to Salzburg this year. And not just a sixteenth tenor standing on the left side of the choir, but as a solo early music performer. For me, this is an incredible opportunity and I feel very happy to be able to do just that kind of music and participate in a festival at this level.

OJ: At the end of the interview, I would like to ask you what creative ideas are still in your mind that you would like to implement in the future?

TTD: I am interested in Renaissance composers who have left such a legacy of creative work which stays forgotten in archives. So there are many works I want to play and record in the future. This summer we will record Heinrich Isaac's work. I would also like to continue my experimental video projects. I want to create a third music video, as well as integrating a facial motive. Other activities are difficult to predict. Every weekend I give a concert at Rochus Church where we perform a Renaissance Mass with the ensemble. I am very proud of this because Renaissance liturgical music is rarely performed in Vienna. We started to work in this church also by chance - we promised to give a concert once, then stay for a year, and now we have been performing there for twenty years. During the holidays we play concert masses, and on a normal Sunday, an a cappella vocal Renaissance Mass. This is a unique musical experience in Vienna. If you have the time, you should pass by and visit us on Sunday.

Tore Tom Denys

OJ: Thank you for this conversation!

Copyright © 6 August 2019

Ona Jarmalavičiūtė,

Vilnius, Lithuania

FURTHER INFORMATION ABOUT TORE TOM DENYS