PROVOCATIVE THOUGHTS:

The late Patric Standford may have written these short pieces deliberately to provoke our feedback. If so, his success is reflected in the rich range of readers' comments appearing at the foot of most of the pages.

Bravado and Introspection

MIKE WHEELER listens to

Rachmaninov and Shostakovich from Daniel Kharitonov,

Vladimir Ashkenazy and the Philharmonia Orchestra

Rachmaninov's First Piano Concerto gives the impression of a supremely confident Op 1, though some of this is in no doubt due to his later revisions. Whatever the case, soloist Daniel Kharitonov conspired with the Philharmonia Orchestra and conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy to give it the most imposing possible start - Royal Concert Hall, Nottingham, UK, 27 April 2019.

The lively section that followed saw Kharitonov scampering up and down the keyboard with playing of both breathtaking ease and pin-sharp focus. On the other hand, while he can unleash coruscating fistfuls of octaves with the best, as he showed both in that opening, and at the start of the first movement cadenza, it was the moments of quiet playing that particularly enthralled, inviting listeners into a very special place. The long unaccompanied passage just after the start of the second movement was typical, conjuring up a barely whispered filigree of both warmth and wistfulness. The finale can seem overly sectional, but soloist, orchestra and conductor made sure the switches of tone between bravado and introspection hung together convincingly. There's also a brashness, and an almost demonic energy, to some of the music which, happily, the performance didn't try to gloss over.

Daniel Kharitonov (born 1998), who won third prize in the 2015 Tchaikovsky International Competition

There's no glossing over anything in Shostakovich's Symphony No 10, whether plain speaking or those moments when he adopts his habitual ironic mask. The initial groping in the dark on the cellos and basses soon acquired a sense of purpose in Ashkenazy and the Philharmonia's reading, with the various woodwind laments threading their way across the epic backdrop, as a sense of menace began coming into view. The big, raw climax was compellingly sustained, after which the two clarinets, moving together in thirds, sounded a tentatively consoling note, while the piccolo duet in the final bars was icily enigmatic.

The blistering scherzo was an outburst of lacerating fury, like a particularly scary musical troika ride, after which the third movement came across with a strong sense of Shostakovich picking up the pieces and puzzling over them, asserting his own personal stake in the process with the insistently repeated DSCH motif that acts as his musical monogram. Against the orchestra's unequivocal cries of protest in the movement's later stages, principal horn Laurence Davies attempted to bring a fragile sense of stability with his equally recurring five-note idea.

More plangent woodwind solos open the fourth movement, and these were allowed to make their points simply and directly. There was a palpable sense of expectation and uncertainty as this big opening section came to an end. Then suddenly it was party time - except that, of course, with Shostakovich, things are rarely that straightforward. Conductor and orchestra left an irresistible impression of a trepak on a large scale, dancing its way towards the huge outburst on the DSCH motif, which arrived with scary-thrilling abandon.

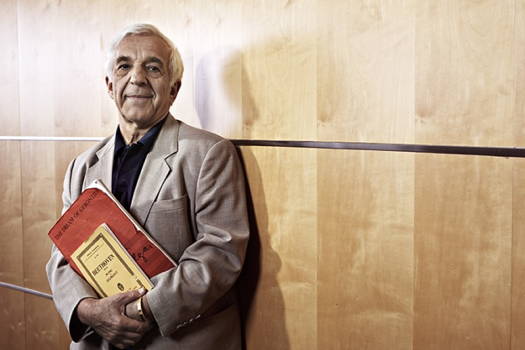

Vladimir Ashkenazy. Photo © Keith Saunders

As it all dies down, a solo bassoon can't resist playing the fool, and Emily Hultmark hit the ironic tone squarely in the middle, while the race to the end left us in no doubt of the ambiguity beneath the exhilaration.

Copyright © 6 May 2019

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK