SPONSORED: Ensemble. Unjustly Neglected - In this specially extended feature, Armstrong Gibbs' re-discovered 'Passion according to St Luke' impresses Roderic Dunnett.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Unjustly Neglected - In this specially extended feature, Armstrong Gibbs' re-discovered 'Passion according to St Luke' impresses Roderic Dunnett.

All sponsored features >>

ARTICLES BEING VIEWED NOW:

- Régine Crespin

- Hector Berlioz

- Ruth Railton

- Marián Varga

- Profile. A Very Positive Conductor - Paul Bodine talks to Los Angeles Opera's Music Director Designate, Domingo Hindoyan

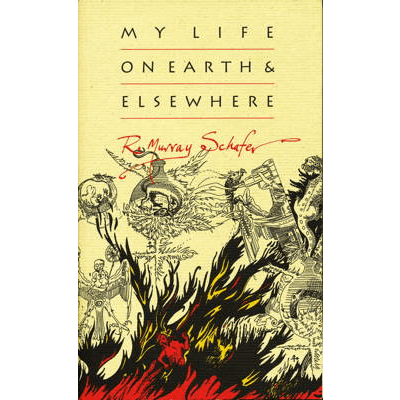

SPONSORED: So Much, for So Many. R Murray Schafer's 'My Life on Earth and Elsewhere', read by A P Virag.

SPONSORED: So Much, for So Many. R Murray Schafer's 'My Life on Earth and Elsewhere', read by A P Virag.

All sponsored features >>

ELECTIVE AFFINITIES

GIUSEPPE PENNISI listens to

German pianist Alexander Lonquich

German pianist Alexander Lonquich

I have reported occasionally on the quite sophisticated concerts organized by the Istituzione Universitaria dei Concerti (IUC), an offspring of Rome's most ancient University, Università La Sapienza. The University was created way back in 1303. Initially located in the city center, near well-known Piazza Navona, it had a new campus built in the nineteen thirties to accommodate some ten thousand students. Now its student population is around one hundred thousand and it has nearly eight thousand employees. Consequently, it sprawls all over Rome, but its main campus and especially its good auditorium with excellent acoustics are intact. The season spans from October to May with two concerts a week, as described in my feature Enthralling Seasons on 24 October 2018.

On 9 March 2019, I was in the audience to listen to a recital by German pianist Alexander Lonquich, who stepped in at the twenty-third hour to replace a colleague who had cancelled at the last moment. Thus, largely by heart, he played a program he had brought with him.

Alexander Lonquich performing for the IUC in Rome on 9 March 2019. Photo © 2019 Claudio Rampini

Lonquich, born in Trier in 1960, studied with Paul Badura-Skoda, Andrzej Jasiński, and Ilonka Deckers-Küszler. He won first prize at the Alessandro Casagrande Piano Competition in Terni, Italy, at the age of sixteen. He is married to Italian pianist Cristina Barbuti; they live in Florence. Although he has as intensive schedule in Italy, both as soloist and conductor, he is a frequent guest of important international festivals, such as Mozartwoche Salzburg, Piano-Festival Ruhr, Schleswig-Holstein Festival, Lucerne Festival, Cheltenham Festival, Edinburgh Festival, Kissinger Sommer, Schubertiade Schwarzenberg, Lockenhaus and Beethovenfest. He has also recorded music by Schubert, Schumann, Poulenc and Mozart for EMI; Fauré, Messiaen, Ravel, Gideon Lewensohn, Schumann and Holliger for ECM New Series; and Beethoven live for the Ruhr Piano Festival. He has received several awards including the Diapason d'Or and Premio Abbiati.

Even though this was a last minute substitution, expectations were high, and they were fully met. The first part of the program was a piano piece of some forty minutes conceived by Lonquich himself and named 'Elective Affinities' after Goethe's novel (Die Wahlverwandtschaften). It merges eighteen fragments of piano compositions by fifteen different composers (from Stravinsky to Beethoven, Adorno to Milhaud, Tchaikovsky to Janáček, Reger to Schumann, Wolpe to Bruckner, Grieg to Rachmaninov, and from Scriabin to Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach). They are composers from different periods and different styles. Fragments were chosen and merged on two criteria: similarity and contrast. The outcome is a splendid unique piano sonata which enchanted the audience.

Alexander Lonquich in Rome on 9 March 2019. Photo © 2019 Claudio Rampini

The second part was Beethoven's 33 Variations on a waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op 120, commonly known as the Diabelli Variations, written between 1819 and 1823. It is often considered to be one of the greatest sets of variations for keyboard along with J S Bach's Goldberg Variations. Musicologist Donald Tovey called it 'the greatest set of variations ever written'. Pianist Alfred Brendel has described it as 'the greatest of all piano works'. In his Structural Functions of Harmony, Arnold Schoenberg wrote that the Diabelli Variations 'in respect of its harmony, deserves to be called the most adventurous work by Beethoven'. Beethoven does not seek variety by using key changes, staying with Diabelli's C major for most of the set: among the first twenty-eight variations, he uses the tonic minor only once. The Variations are considered so complex that even Horowitz never gave a public performance. Toscanini said that he listened to a private Horowitz performance and thought that nobody could play the piece like him.

Lonquich gave a masterly rendering by playing without a score with dramatic effects at the key change, in the fugue and in the closing minuet.

At the very warm applause and requests for an encore, Lonquich turned romantic and played Chopin's Impromptu No 2.

Rome, Italy