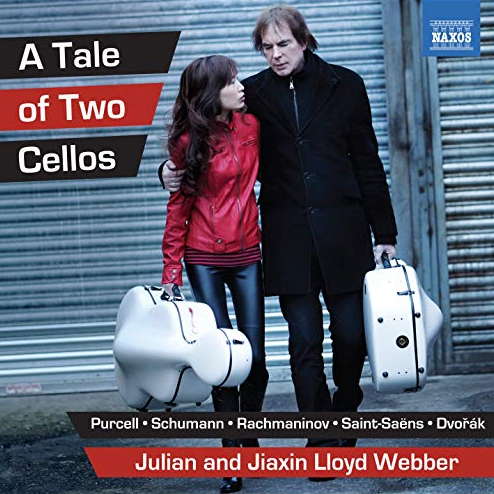

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Uncommon Piquancy - Music for two cellos, heard by Howard Smith.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Uncommon Piquancy - Music for two cellos, heard by Howard Smith.

All sponsored features >>

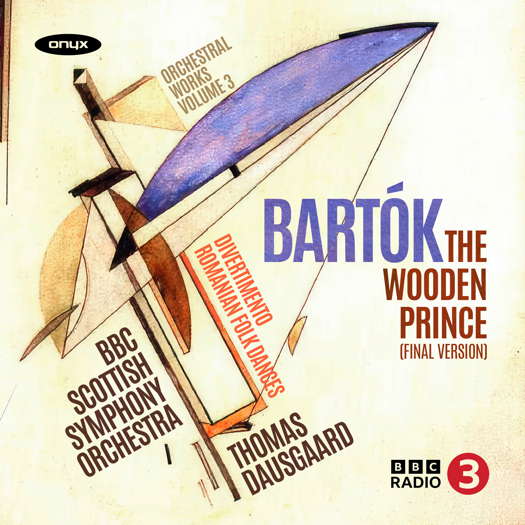

Mysteriously Fascinating

GERALD FENECH wholeheartedly recommends orchestral music by Béla Bartók

'The BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra plays flawlessly throughout.'

Béla Bartók was one of a handful of early twentieth century composers who recognized how indigenous folk music could fuel a new sort of progressive concert music. Born in an area of Europe rich in peasant culture on 25 March 1881, he soon set on a path of intense musical training in the classical tradition. Bartók was initially taught the piano by his mother and when, in 1899, the family moved to Pressburg, now Bratislava, the young boy soon enrolled at what is now the Liszt Academy in Budapest, where he would eventually replace its piano professor István Thomán.

By the 1910s, Bartók had become increasingly interested in collecting and transcribing folk tunes and dances from Hungary, Romania, Croatia and Yugoslavia. Indeed, this enthusiasm even spread to Turkey and North Africa. He did so with rare dedication, for decades. These melodies and rhythms lit the fire of inspiration within Bartók, who started to conceive music that fused their characteristic elements with the highly developed musical language of the day. His works managed to unite these two contrasting worlds with rare conviction and universality of feeling, in music of striking power and focus.

By the 1940s, Bartók was a well-known figure, not least as a performing artist. He left for America after Hungary aligned itself with Hitler during the Second World War. The composer struggled in the US, securing a professorship but few commissions or performing engagements, until he was thrown a creative lifeline by a fellow émigré. Towards the end of his life Serge Koussevitsky commissioned a string of orchestral masterpieces, including the famous Concerto for Orchestra.

Bartók died in New York on 26 September 1945, less than a month after the War had ended, leaving a legacy that has been taken up by many composers after him. Indeed, many today research folk music and then use their findings to create progressive concert music that spoke of a nation.

This fine album includes three works that are not so frequently performed. The one-act pantomime ballet The Wooden Prince (1914-1916) was premiered on 12 May 1917, but although it never achieved the fame of Bartók's other ballet The Miraculous Mandarin, it was enough of a success to prompt the Opera House to stage the opera Bluebeard's Castle the following year.

The Wooden Prince is the story of a prince in love with a princess, but is stopped from reaching her by a fairy who makes a forest and a stream rise against him. To attract the princess's attention, the prince hangs his cloak on a staff and fixes a crown and locks of his hair to it. The princess catches sight of this 'wooden prince' and comes to dance with it. The fairy brings the wooden prince to life and the princess goes away with that instead of the real prince, who falls into despair. The fairy takes pity on him as he sleeps, dresses him in finery and reduces the wooden prince to lifelessness again. The ballet ends with both royal lovers united together to live happily ever after.

The second of Bartók's stage works, this ballet never achieved the popularity of Bluebeard's Castle or The Miraculous Mandarin, the possible reasons being the heavily symbolic scenario by Béla Balázs and the largest orchestral ensemble ever utilized by the composer. Indeed, the music belies echoes of Richard Strauss, Claude Debussy and, most of all, Richard Wagner. How can one not be reminded of the Prelude to the latter's Das Rheingold exactly at the opening of the work?

Listen — Bartók: Introduction (The Wooden Prince)

(ONYX4233 track 1, 0:02-0:58) ℗ 2024 BBC :

Also, parts of the score seem to look back at previous compositions by Bartók and to the roots of his very unique style. There are some edifying passages that are the fruit of Bartók's gifts for orchestration, but the music lacks that striking element which makes you stand up and listen. No wonder Bartók was not satisfied with the piece and he kept revising it for twelve years. It's this final revision that has been recorded on this issue and this appears to be the first ever recording of this ballet in its final form, which is thirteen minutes shorter than the original.

Listen — Bartók: The Dance of the Trees (The Wooden Prince)

(ONYX4233 track 5, 0:45-1:45) ℗ 2024 BBC :

The Divertimento for Strings was composed in 1939, just before his emigration to the States. This was a stressful time for Bartók, due to the impending War and his concerns over his elderly mother in Budapest. The Divertimento was completed in just fifteen days, during which other concerns all but disappeared for the composer. The serene surroundings of Paul Sacher's alpine chalet might be one reason why this work is considered as one of Bartók's more accessible pieces. The Divertimento can be said to follow a Baroque template for the 'concerto grosso' with a solo group of four strings foregrounded against a larger 'ripieno', but the sound is far remote from that of an era two centuries backward. The work unfolds from a lighthearted opening through a darker movement marked 'adagio' and ends with an effervescent rondo built around a double fugue.

Listen — Bartók: Allegro assai (Divertimento for Strings)

(ONYX4233 track 22, 0:00-0:59) ℗ 2024 BBC :

The programme is rounded up by six Romanian Folk Dances replete with vibrant rhythms and audacious harmonies.

Listen — Bartók: Buciumeana (Romanian Folk Dances)

(ONYX4233 track 26, 0:49-1:22) ℗ 2024 BBC :

This album is the third in Thomas Dausgaard's survey of Bartók's orchestral works, and as in the previous two, he has recorded a version of a major work seldom performed; and, again as on the preceding two discs, his conducting is nothing short of compelling. Indeed, he is consistently 'inside' this arresting music without ever being vulgar or too laid back. The BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra plays flawlessly throughout.

I must admit, I am not a big admirer of this composer, but this issue has certainly roused plenty of interest in me, and I am starting to think again. Recommended wholeheartedly, especially to those, who like myself, are still somewhat lukewarm to take the plunge in Bartók's mysteriously fascinating sound world. Presentation and sonics are first-rate.

Copyright © 15 April 2024

Gerald Fenech,

Gzira, Malta