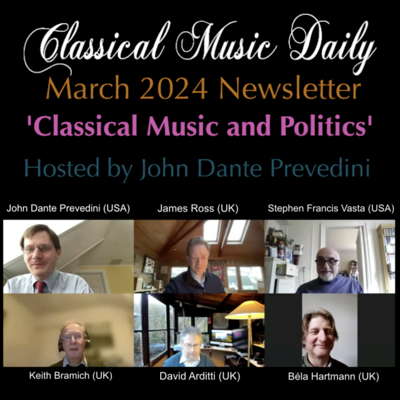

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Politics, including contributions from Béla Hartmann and James Ross.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Politics, including contributions from Béla Hartmann and James Ross.

- Johann Simon Mayr

- Franz Beyer

- Ableton

- Schreker: Der Ferne Klang

- Mathias Grimminger

- Cipriani Potter: Introduzione e Rondo (alla militaire)

- International Parisian Symphony Orchestra

- Lehár: Paganini

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Most Remarkable - Jamaican pianist Orrett Rhoden, heard by Bill Newman.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Most Remarkable - Jamaican pianist Orrett Rhoden, heard by Bill Newman.

All sponsored features >>

It's Art

RON BIERMAN talks to Amerian opera director Kyle Lang

Opera conductor Kyle Lang and his husband Christopher Kaui Morgan recently moved to San Diego from Hawaii. Morgan was chosen out of more than thirty candidates to become artistic director of the area's Malashock Dance, and Lang has been part of various San Diego Opera productions for nearly a decade, initially as assistant director, then stage director.

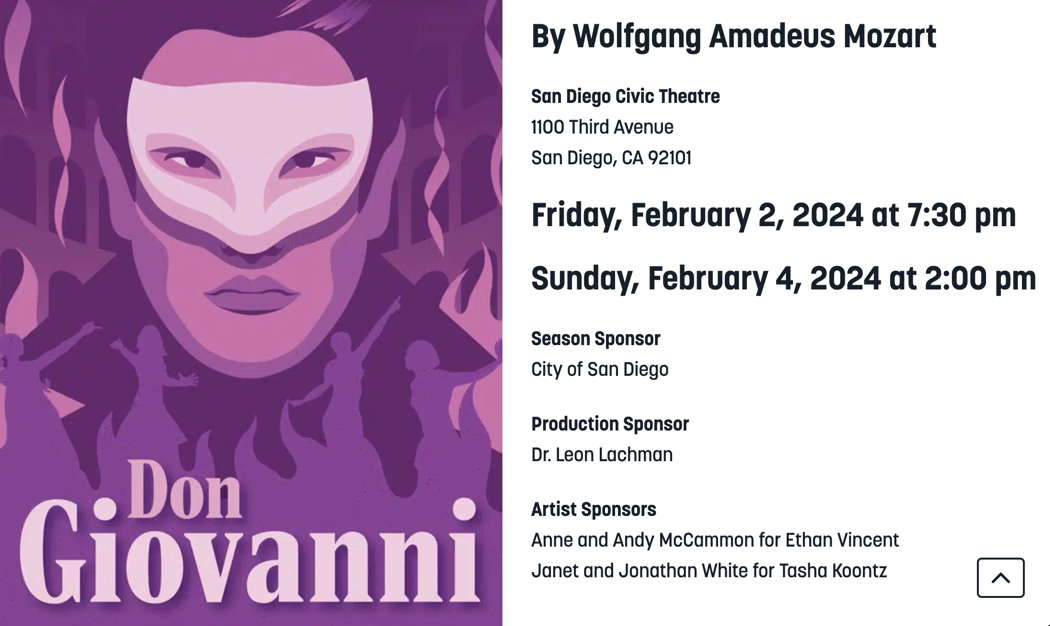

Lang is directing the company's upcoming performances of Mozart's Don Giovanni. In a recent conversation via Zoom we spoke about how he came to be a director, his approach to directing and specific thoughts about one of Mozart's finest achievements.

Kyle Lang

Lang first became interested in music as a young churchgoer.

It started with me in my daddy's lap playing with the music on the back of the pew in front of us. And my parents were oh, we need to start having piano lessons. So I started learning the basics, classical piano at first, but then I played in church, and in summers I would go to a church music camp where I learned stride piano. It's kind of the Southern gospel I grew up with.

He wasn't thinking about a career in music at that point, but after high school he did go to the University of Southern Mississippi as a piano performance major.

About a year in at USM, I just couldn't sit in a tiny room with a piano anymore, so I kind of did the opposite - dancing. I don't think I'd ever felt like playing the piano was going to be my career. I just knew that my career would be in making art.

He went on to earn a BFA in dance from New York University's Tisch School of the Arts.

Out of finishing school at Tisch I auditioned at the Met and went straight to work there that next season. I was like wow, this is amazing! I'd never been around voices like that.

I danced in opera for like twelve years, and for a couple of ballet companies and contemporary dance companies, one in New York called Zvi dance for a long time while still doing opera ballet. I did nine seasons with the Met, then I started doing stuff at Washington National and Chicago Lyric Opera. I was just dancing around kind of at the top of my game, getting great contracts.

In 2007, I went to Santa Fe for the summer and got to dance in a couple of wonderful shows. It was different there because we were used in staging as well as dancing. So we were part of the rehearsal process. It just changed everything. It was wonderful to be told not to do anything for thirty minutes. I just watched the director and fell in love with it. It was about performing, and that's what I've loved so much. Performance was what I loved about piano.

When I was ready for something different, a friend suggested directing. I spent three or four years assisting, and because I could choreograph, companies saved money by bringing me in to do both. I began directing without also choreographing in 2016, and that went well.

I didn't realize then how one thing was leading to the next, but I couldn't be doing what I'm doing now without both the musical background and the dance vocabulary - the understanding of art, time and space. So as a director, that's the way I approach things. I first ask what the story is and what is the company wanting to bring to their public? Then what can we do with the time that's given, and what happens spatially. And of course, everything comes from the libretto. So, space is a result of what's being said and who's talking to who. It's always a nice puzzle to figure out and to find new approaches.

And each composer is different. Rossini will have written a reaction that should have taken five seconds and turned it into two minutes. So you have to learn how to stretch time. Mozart wrote things that happen in a split second. A simple glance can be very important. Puccini gives you the staging in the music. I don't want to say he's the easiest, but he did a lot of the stage director's work.

Lang spoke of the importance of collaboration in working with the cast and others in the company.

I never go into a rehearsal room and say, do it this way. I'll say try it this way. And then if that's not what works for the singer or actor, it's a bit of a conversation. They have to feel like they're being honest about what they're doing. Let's figure it out. Let's talk about what's right or wrong. I just want the right answer, and it doesn't have to be mine.

People can't feel stifled on stage and at the end of the day, I'm not the one doing, they are. So they need to feel the best they can about it and feel supported the entire time. You know, we have a very short rehearsal process for Don Giovanni, so I have to rely on the singers to really allow themselves to let go and almost improvise at times.

Lang said that earlier in his career he:

... tended to get wrapped up in a lot of comedy. That's kind of where I'm most comfortable. It's certainly harder because it takes more time to rehearse, but I think as a dancer, I have a feel for the right timing. Figaro is my favorite opera.

When I asked if there'd been a particularly satisfying moment in his career, he recalled a performance of Die Fledermaus.

It was the first time I really tackled comedy on that level, and it was going to be either fun or a disaster.

He feared an early joke based on a Rocky Horror Show scene would fail because the audience wouldn't get the reference.

Opening night I'm always cringing. But the audience laughed at the joke and never stopped laughing the entire rest of the show. That was, for me, a kind of revelation that I was in the right place. A place where I felt most alive. The rehearsal process and energy translated to the performance, and I thought, not only can I do this thing, it's what I'm supposed to be doing.

This is the first time Lang has directed Don Giovanni, an opera with comic elements, but ultimately a tragedy. Mozart was more than comfortable with emotional complexity, and it will be interesting to see how Lang balances the mix.

Giovanni is so different, it's quite special. And I tend to be good with choruses and large numbers of people moving around the stage. Once I get a feel for what's happening with the creative team and the costuming, I start imagining the show and dreaming of how I'm going to stage it. For most scenes, I have three different versions of how, and what I generally arrive at in rehearsal is a combination of the three.

That happens in the rehearsal room and is my favorite part of it all. I love being in the room with good actors who want to find something to say through the piece, and sometimes that can just be saying, 'Hey, I have an awesome voice. But I've spent twenty-five years - how many await?' Like it's a gift we should be sharing with the world. So for me, as a director, and about telling a story by allowing people to share themselves with an audience, about them being a conduit of energy flowing through, not being pushed.

Lang's collaboration includes the audience.

Yes, and you know, sometimes I'm like, well, this is how I feel about this, and the audience may not like that. But maybe it'll make them question something. And especially in today's world, I kind of feel like there are a lot questions.

Collaboration, of course, must have its limits, especially if rehearsal time is relatively short.

It depends on the show. There are moments where I'm no, no, no, no, that's not up for debate. It has to happen like this otherwise it's not going to be funny because of the timing, for example.

Don Giovanni has a lot of interpretations, more than any other opera, people have different opinions about what's really going on. I'll share mine with the cast, and they'll share theirs with me until we figure out what these characters are. But I feel there are no good and bad characters in the show. I don't see the Don as a hero or a villain. I just see him as an immoral or amoral person.

Online publicity for San Diego Opera's Don Giovanni

I do think some of his actions are despicable. But there are certain impulses that he has that I've thought about myself, only he acts on them. He has no self-control, just reacts decisively to what just happened, not following a masterplan. And it takes a supernatural superpower to bring him down.

I spent some time using Myers Briggs character analysis to help decide how to think of the opera's personalities. You know, they're all pretty extroverted. Leporello is like the count.

He described opera as not in a terribly good place now.

After the pandemic, it's been hit harder than any other art form. The NEA [National Education Association] did extensive research last year about that, and opera is suffering more than any of the other arts, even dance. There are many factors. Younger audiences have different tastes. They will pay a thousand dollars for a ticket to a rock concert. Can't we get them interested in opera?

Opera is often thought of as expensive entertainment, but even excellent seats cost a fifth as much.

But then there's also funding for the arts in the United States. It's embarrassing, especially compared to, not just Europe. Compare it to Canada. Politically, we don't understand that art is a way to heal and move forward, to prevent problems before there is even a hint of them. The arts teach social respect, and appreciation for human humanity.

I direct opera because I am interested in telling the story of the human condition. I try to identify with every character because we're all people, and there's at least a little bit of the character in everyone, even if never acted on. This show is about impulse control, and I can totally relate to every character though never acting on any of their impulses.

I think we're suffering as an art form because we're not understanding how the beauty of art can help us in our day to day lives. When I was a child through the 80s and 90s, art was seen as fluff, a fun extra, not a part of our community. But I grew up with church music that was a very important part of our community. There's a similarity between that and painting. They are both art, and art needs to be cultivated in our schools.

Lang also believes that new operas and opera productions must find better ways to appeal to modern societies.

We have to figure out what opera is going to make a thirty-year old want to buy a ticket. Once we get them in, maybe they'll get the music. It's like learning a language. Visually and aurally, we have to introduce a modern language to thirty-year-old people. For the most part, they don't want to go see something in period costume. They just don't, unless it's like Hamilton, which modernizes with rap. Then there are also ways of producing it like immersive theater, people eat it up.

I would love to do a Figaro where the tickets are a thousand dollars and you come in to a mansion of like thirty people who are the characters. Cool. You know? Then there's also finding new ways to attract people online. And composers are trying to do more with contemporary themes. We need more modern stories, but companies are afraid to do them. It's art. Some people are going to love a painting, and some aren't. If we're afraid of that, we're not creating the soulful art that could change lives.

Having spoken about the future of his field, I asked what he would like to do next.

I'd love to do Handel with a lot of dancers so I can rehearse them and use my skills as both a director and a choreographer in the same production.

And I've done some Broadway shows including Showboat and Oklahoma, which was written for opera singers. I love the older musicals and haven't done anything new, but there are a couple I'd love to do. We'll see what comes. Particularly Rodgers and Hammerstein have more underneath the surface than people realize.

My final question was 'What do you hope the audience gets out of this production of Don Giovanni?'

I hope that everybody gets something they did not expect. Something that surprises and delights.

Copyright © 29 January 2024

Ron Bierman,

San Diego, USA