SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fascinating Recording - John Joubert's string quartets, heard by Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fascinating Recording - John Joubert's string quartets, heard by Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. On Buoyant Form - Orchestral music by Andrew Downes, heard by Roderic Dunnett.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. On Buoyant Form - Orchestral music by Andrew Downes, heard by Roderic Dunnett.

All sponsored features >>

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Melting Rhapsody - Malcolm Miller enjoys Jack Liebeck and Danny Driver's 'Hebrew Melody' recital, plus a recital by David Aaron Carpenter.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Melting Rhapsody - Malcolm Miller enjoys Jack Liebeck and Danny Driver's 'Hebrew Melody' recital, plus a recital by David Aaron Carpenter.

All sponsored features >>

A Magnificent Undertaking

RODERIC DUNNETT was at Adrian Partington's 2023 Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester

There may be longer UK music festivals - Edinburgh, the Proms, Cheltenham; possibly Brighton and Bath. The now rich and distended Oxford Lieder Festival this October. And in another field, Hay-on-Wye's far-reaching three-week Literary Festival.

But for all this the Three Choirs Festival is unique, in its interweaving of - above all - absolutely amazing full choral cathedral concerts every evening - with daytimes packed with events of all kinds: chamber, consort, vocal, keyboard, instrumental - over eight days.

It's rare - next to impossible - to feel let-down by this magnificent triple festival, at any one of its three outlets - Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester. A combination of the major English choral composers (above all Elgar, and in this anniversary year, Vaughan Williams). But often you may encounter the less familiar: the lesser-known Elgar oratorios, Poulenc or Kodály, let alone Sibelius, Nielsen or Rachmaninov or - an outstanding example - Samuel Hudson at Worcester had planned a major work by the American Boston- and Munich-trained Horatio Parker (1863-1919), admired and befriended by Dvořák, before Coronavirus played havoc, plus a substantial input - this time round, a flood - of commissions in virtually all genres.

Gloucester, under this year's Artistic Director Adrian Partington, ticked all the boxes. It began as it meant to go on - with a bang. This must have been as dazzling, perceptive, daunting and delicious a reading of the Elgar Violin Concerto as any heard in England this year, or possibly any recent year: they are rare anyway. This dazzling experience benefited from five contributors: the resident Philharmonia Orchestra; the soloist (and the orchestra's co-leader), Zsolt-Tihamér Visontay, a startling performance and astonishingly powerful insight, the two emerging in a staggeringly vigorous, indeed awe-inspiring performance; and, contrasting with the drama, which was overwhelming, the leader this week, Rebecca Chan, whose every intervention was as pure as a wafting skylark. Everything about Visontay's playing seemed to shed an entirely fresh light on this work so frequently overshadowed by Elgar's irresistible cello concerto, in part a lament for his dead wife. But Visontay - the very long bows and astounding refinement thereof, his attack deployed almost like a short, stabbing sword or rapier; his remarkable ability to pick up the instrument and instantly launch (or lurch) in: utterly overawing.

Co-leaders of the Philharmonia Orchestra: Rebecca Chan (photo © Marina Vidor) and Zsolt-Tihamér Visontay (photo © Guy Wigmore)

Crucially to this staggering display was, of course, the intimate control of Adrian Partington. (The 'home' conductor usually directs three evening concerts, and the other two at least one of the big choral evenings each.) Partington had the same night seen the forces through the first commission, from Eleanor Alberga, a superb West Indian-born British composer who contrived to extend her ten-minute plotted commission to nearly a quarter of an hour. A classic symphonic poem, although, to some degree, as can be with such a work, lacking any feeling of direction. From a composer with such an acute sense of structure and orientation, rather a medley of styles. Dare one suggest, not her best?

Yet it was Partington and Visontay's supreme shared gift for clarifying the spirited twists and turns in Elgar's orchestral lines, some wonderful, expert fading to nil, those eerie interstices, or subtly rocking strings, the often unforeseen outbursts, some sudden key shifts in those passages suggesting other Romantic concertos of the period, yet never less than original: this was a performance bathed in excellence. Possibly 'Ye shall never hear its like again.'

An accolade for a quite different aspect of all these multiple concerts: the extensive notes the Three Choirs includes in its accompanying Programmes. Not least, the individualistic, amusing and incisive contributions of The Spectator's Richard Bratby excelling and entertaining in the case of the Elgar Violin Concerto, Bax, Holst, and, on the final night, Elgar's The Apostles. But one benefited greatly from scholarly observations by Peter King - especially the repertoire-rich organ recitals, Hannah Roper, Greg Murray, Liz Lane, Paul Ellison (St John Passion and other Bach), coupled with the expertise of Andrew Burn (The Pilgrim's Progress), and regular contributors, not least the articulate, thoroughly researched, Gwilym Bowen; plus peppered with revealing insights from the composers or indeed the performers themselves. Add to these full texts and translations - especially helpful for new choral works - and the result is a programme book that is a first-rate keepsake, especially if built into one's library year on year.

Add to this the lectures, often illustrated visually or vocally: on Elgar's notebooks; on the Three Choirs' original mover, William Hine - a composer to set alongside Purcell and others of that era; pioneering medic and smallpox vaccine inventor Edward Jenner (whose statue honours Gloucester Cathedral's west end); on Vaughan Williams' Tallis Fantasia (heard not just in the orchestra but in a totally fresh and unexpected choral arrangement, introduced by the visiting ORA Singers); talks on music therapy; and on Sir John Squire, who almost single-handedly launched the careers of numerous so-called 'Georgian' poets, but also an enabling editor of many more. In these literary aspects alone the Three Choirs unearthed many nuggets of sharpness and insight.

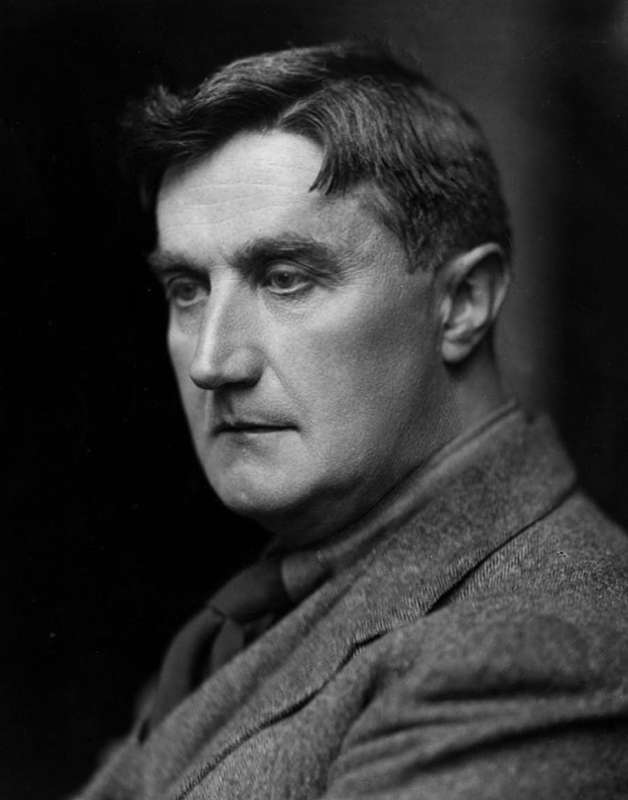

Ralph Vaughan Williams. Photo © 1921 E O Hoppé

A knowing friend told me beforehand that he could never come away from Vaughan Williams' Sancta Civitas (The Holy City) without a feeling of doubt: that this was not as expressive or piquant as so much else of the composer's output. I have not especially felt that before, but I sense I came with that opinion affecting me, and I fear some of that disillusion affected me. Its opportunities for such a weighty and intelligent choir - who, always reliable, well-defined and at best creatively coloured - left something to be desired.

It is an attempt to explores passages from The Book of Revelation, but there was nothing here to compare with, say, The Book with Seven Seals, by Hungarian-Austrian composer Franz Schmidt - an awesome oratorio, crying out for a Three Choirs premiere. Perhaps it was in the choral writing, perhaps the orchestral; perhaps both. The might and power - and fear and horror - of those texts demands a fire, explosiveness and terror if it is to stand alongside such a masterpiece as VW's The Pilgrim's Progress. Indeed the orchestral soothings, sometimes lightness, of Flos Campi the following night, dating from just a year before Sancta Civitas (1925 and '26) seemed much more to VW's taste.

Or else, for such intensity, one can look into Dona nobis pacem, his Great War elegy, where his fondness for Walt Whitman - dramatic, reconciling, grieving - and drawing on Old Testament extracts as well, seem closer to the composer's heart, and his personal preoccupations and inclinations; his innermost self.

Sunday's main concert was a special delight. One was massively impressed by two new or newish works that slightly oddly surrounded VW's Flos Campi, with its wordless chorus - an echo of Ravel's entrancing (and orgiastic - Gwilym Bowen's note) Daphnis and Chloe. It was sung with intense expression by the Three Choirs Festival chorus, with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales - the Philharmonia being elsewhere for three intervening nights - overseen by that master of English repertoire, conductor Martyn Brabbins.

One was Ronald Corp's Hail and Farewell, a premiere of nearly twenty minutes, each movement of which had its own defined character, moving or celebratory, yet meshed together into a deeply satisfying whole. Several movements - there are seven - are so buoyant they call to mind the most electric movements of Britten's cycle Les Illuminations. Perhaps this is because No 2 ('Tournez, tournez') gets its fairground atmosphere from a setting of Verlaine - words that in their way look forward to Myfanwy Piper's pithy image-packed libretti for Britten: the vibrant, joyously jerky sixth section is indeed entitled 'Roundabout'.

The contrasting seriousness dwells in No 4, Catullus' profound lament for a brother tragically lost, its desolation unyielding and so distant from the joys of his favourite Sirmio, on Lake Garda, and a less familiar, grieving Shakespeare sonnet. ('... I all alone beweep my outcast state ... and then, taking wing' ... 'Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising, Haply I think on thee, and then my state (like to the lark at break of day arising ...')

Corp knows how to make music sing: indeed his concluding Robert Bridges song ('My spirit sang all day' - also set as a partsong by Gerald Finzi - riddled with melismata, stretching syllables highly effectively across several notes) sings just like another lark ascending: the whole work is pure rapture.

Stealing the honours on this evening, though, was a forty-minute quasi-opera by Gavin Higgins. Two obvious connections: just turned forty, he was born in Gloucestershire and grew up in the Forest of Dean, progressing thence to Chetham's School of Music and Manchester's Royal Northern College of Music; furthermore he is Composer-in-Association with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, of which Adrian Partington is Chorus Master - and indeed the orchestra performing that night in Gloucester Cathedral.

The Faerie Bride, composed last year, draws on a classic Welsh folk-tale, the story (like Dvořák's Rusalka) of a water-maiden who emerges to marry a human, but never accepted by the people above. The marriage fails, spoilt by the chidings she incurs, and she returns to the lake with all their family and possessions. Graphic stuff.

This semi-opera proved a triumph. Francesca Simon's text is carved and incised like a pure piece of alabaster, and Higgins matches her with a score that adheres to - captures and vitalises - the short lines of the story rivetingly. It is indeed a collaboration clothed in inspiration. Indeed the pair had already provided, in 2019, an opera for Covent Garden, based quite similarly on a (Norse) myth.

Higgins' orchestral 'Prologue', with double basses, cellos and horns atmospherically prominent, was a revelation of things to come. Stylistically individual, even though it felt (slow, still, dark - appropriate) not unlike Das Rheingold meets Peter Grimes (whose villagers' outcry it matches and betters). Hanging the text deliberately on repetitions, or near echoes - tentative, atmospheric ('Watching. Waiting.' 'The moment I saw ... breathed ... heard.' 'The bread. The half-baked bread.' Or the villagers' brutal 'Don't like her, Don't trust her, She's not from here.' 'Everyone ... everyone ... everyone.' And as the marriage falters and dies, 'Well-a-way Well-a-way'; 'deeper and deeper'; 'Till tomorrow.') It cannot be exaggerated how important this approach to textual construction is. The composer, of course, can repeat a melody, a fragment as often as he, or she, wants.

Gavin Higgins, whose cantata The Faerie Bride with librettiost Francesca Simon proved one of the most sensitive and inspired offerings of the week

All the time, Higgins is manipulating his instruments up inviting paths. Stunning orchestration permeates the early build-up to the watersprite accepting her invitation. His use of woodwind both individually and as an ensemble works to beguiling effect. Bass clarinet, oboe, the prominent bassoon as she warns the man of the likely (unhappy) outcome, downsliding at the loss of a child; the bursting brass (almost a Peter Grimes Sea Interlude) as she proclaims an end to the romance.

It is not just in the repetitions, and their intensification of both the raising of hope and descent into gloom, that Francesca Simon's writing shines through: deceptively simple, but incredibly atmospheric. We meet it at the very start: 'The lake is dark today. Glacier cold.' (All the full stops intensify the effect: each comment is allowed to echo on, to enrapture or distress you.) 'She fixed me with her lake eyes, blue green grey.' (For once, no intervening full stops.) 'Golden, joyful years ... Our flocks covered the hills. Our wheat grew as high as the house.' 'She waves at the moon, She sings to the cows, She swims naked ...' And latterly, 'Brindled cow, spotted cow, speckled cow, come home. Little black calf, jump down from the meat-hook. Fat slaughtered pig, flee the butcher's knife. Live again.' An astounding text. Astonishing poetry. The writer whose deployment of images comes closest to Simon is arguably the wondrous Orkney poet, George Mackay Brown.

Simon has a similar gift for turning the simple, the homely, into the incredibly sensitive and touching. Her manner does indeed share a great deal with old folklore texts themselves. Or she achieves a similar effect. Someone who has tried to do the same is David Pountney, in his text for Peter Maxwell Davies' opera The Doctor of Myddfai, based on a similar mid-Wales sprite story and premiered in the 1990s by the BBC NOW's sister company, Welsh National Opera.

Vaughan Williams' long-gestating opera The Pilgrim's Progress, in which John Bunyan's hard-pressed and hectored traveller, naïve but aspiring after goodness, makes a Peer Gynt-like journey through a motley crowd of dodgers, ne'er-do-wells, malpractice-wallowers and dubious well-meaners, was a magnificent undertaking by Partington and his Gloucester Committee.

It requires, even with doubling, or rather, trebling, a substantial cast - a galaxy of young singers, including the Three Choirs Festival Youth Choir, recently formed, or now united - and a conductor able to gauge a way through the wild goings-on, as opposed to the more amiable, pastoral, reassuring, upheld by some typically blissful orchestration. Conducting with ever-present insight, Charlotte Corderoy, herself a former member of the Gloucester Cathedral Youth Choir, won some of the most resounding cheers of the whole week.

And resound it did, from the opening solo of Bunyan himself (baritone Emyr Lloyd Jones), who sings both prologue and epilogue: among the most haunting passages in VW's entire output, through the encouragement of Three Shining Ones (SSA), the abysmal carefree lustiness of Vanity Fair (temptation, but never really likely) presided over by tenor Gabriel Seawright's rampant Lord Lechery, the grim exchanges with Lord Hate-Good (Jia Huang) and the curious bass(-baritone) monstrosity Apollyon (Armand Rabot) to the gradual revival of light as the final vision unfolds itself. To begin to pay sufficient tribute to this extraordinary, varied and inventive score would seem near-impossible.

But highlights were (inevitably) the patent honesty of baritone Ross Cumming's determined, hard-journeying Pilgrim, symbolically load-bearing ('your burden'), striving to find a way to access eternal purity and light, manfully feeling his way past the faint hearted, the objectionable and the downright evil among the characters paraded in this saga, abetted - to my mind admirably - by the most simple of 'sets', a collection of boxes shifted and piled around the cathedral stage (and pillars, manoeuvred by members of the splendid British Youth Opera, who played most of the roles alluringly), and utilised by Director Will Kerley instructively and contrastingly so as to differentiate each scene. Some found the device weak. Far from it, I felt it ideal: it worked amazingly.

If those Three Shining Ones ('Now shall thy peace be as a river, and thy righteousness as these') prepare him for his long haul, Vaughan Williams' proclamatory Herald (Huang again) is one of the most powerful dramatic, assertive pieces in all VW's output (think, for instance, of his Sixth Symphony): he it is who points Pilgrim to 'the whole armour of light', opening the way (textually and musically) to one of the finest choruses in the piece.

The infusion of the score of this 'Morality' by the hymn tune 'York', with its eerie interweaving of major and minor, and a few similar mottoes, helps splice the whole opera together. Much seems to be prised from it to interact with individual scenes. It can be traced back to 1615, or precisely Bunyan's time: one Scottish Psalter mischievously describes it as 'tottering': not wholly inept, regarding its shifting chord sequences. But such is its demeanour, one could easily imagine it dating back, in outline at least, to the fourth or fifth century.

Sometimes it appears, as harmonised, plain and simple; sometimes it breaks into pieces; or it can be counterpointed by, for instance, dissonant brass blasts. It is here assertive; here elusive. With bizarre costumes Kerley's Vanity Fair farrago emerged with all the alluringness of, say, parts of Petronius' Satyricon, or the fairground touches in that other 'progress', Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress. When it turns nasty - Pilgrim's outburst, 'Ye workers of iniquity, whoremongers, murderers and idolators' - Vaughan Williams' special gift throughout his work for giving leash to the tuba is mightily effective.

The later stages are enchanting. A Forester's boy (Angelina Dorlin-Barlow), blithely and innocently singing, guides him in the direction of the sought-after 'Delectable' Mountains. A perky but ineffectual pair arouse then quash his interest. Easily the most inspiring exchanges come with three shepherds, somewhat poetic and visionary as well as humble beings who see it as their God-given duty to offer hospitality to 'a wayfaring man'. A bird (Issy Bridgeman) sings a more or less unadorned 23rd Psalm; and Pilgrim has indeed been through both the dark and the restorative, lightening sequences of that psalm. As he comes within sight of 'the Gate', Heavenly voices pour around. The sense of redemption which infuses the close of all three of Elgar's principal oratorios is now swathed around the traveller. Pilgrim has achieved his salvation. Bunyan has told his tale.

There have been, but only intermittently, staged productions of Vaughan Williams' opera, first seen in 1951 at Covent Garden. Roderick Williams, for instance, sang Pilgrim, for English National Opera, semistaged, at Sadler's Wells in June 2008, the fiftieth anniversary of VW's death, under Richard Hickox, who was to die, aged sixty, only five months later. This Gloucester Three Choirs performance, handsome and well thought out and highly affecting, with a terrific, supercharged chorus, can stand in the memory with the best of them.

There were three organ recitals - that is usual, by young performers making their way. What stood out - perhaps it commonly does - was the richness of the repertoire which, taken as a whole, they shared to fine effect. Not just three recitals, but three organs - three venues. The Victorian Gothic, Anglo-Catholic Grade One-listed (and highly decorated) All Saints, Cheltenham - a four-manual Hill organ of 1887; Cirencester Parish Church (a new Harrison instrument. Also four-manual, replacing the Willis of 1895); and St Peter's Roman Catholic Church in Gloucester itself, closely connected with the city's substantial Polish community, a two-manual Compton replacing an 1850s predecessor, recently done up by Nicholson of Malvern, and furnished with an unusually rich array of stops, including mutation 2 + 2/3rds and brass, tremulant, plus a pedal trombone.

Guernsey-born, Wells Cathedral School-educated François Cloete (subsequently an organ scholar at Hereford, now Merton College, Oxford) introduced Gustav Adolf Merkel (1827-85), Schumann pupil and Mendelssohn admirer, and head of the Dresden Singerakademie - in fact he held just about every major post in the Saxon capital: his Sonata No 5 (a work Cloete included in a recent recital at Merton); in fact Merkel wrote nine sonatas, plus chorale preludes and much else. Cloete also served up an astounding roundoff, a typically massive Max Reger 'Choralfantasie' entitled Hallelujah! Gott zu loben, bleibe meine Seelenfreud!

Reger died in 1915 aged forty-three, one of twentieth century music's tragic losses (like Mus(s)orgsky in the nineteenth), but his organ output remains mountainous. This was one of his (many) works that, neo-Bachian no less, carved into by pianissimo interludes, invariably bring the roof down. Miriam Reveley (since childhood Ely Cathedral and subsequently St George's Chapel, Windsor) scintillated at St Peter's in three French composers - Franck, Vierne and Boëllmann. But - a surprise - a three-minute devotional piece, Adoration, by African-American composer (and symphonist) Florence Price (1887-1953).

Polina Sosnina, organ scholar at many outlets, most recently the London Oratory and St Martin-in-the-Fields, delivered Franck and Duruflé, but also - a real unexpected - the short but telling Passacaglia from Shostakovich's opera Katerina Ismailova (Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk). Each player pulled off a major work by Bach, all famous: Sosnina, the magnificent C minor Passacaglia and Fugue (a follow-up to Buxtehude's own celebrated Passacaglia, in D minor), Reveley the scintillating G major Prelude and Fugue, and Cloete the explosive G minor Fantasia and Fugue. This was hefty stuff, enough to excite any audience.

Two groups were brought in to enhance the evening concerts. The first, Suzi Digby's young and alive ORA Singers, cleared Tallis' Spem in alium at a pace. It can be catching. Robert Hollingworth and his consort I Fagiolini have rediscovered and recorded, now on The Sixteen's Coro label (COR 16199), the forty-part Renaissance masterwork by Alessandro Striggio (Florence-Ferrara, 1536/7-1592); while Ora themselves have commissioned a brand new forty-parter, likewise roughly ten minutes long, from Sir James MacMillan, Vidi Aquam, which they recorded three years ago on Harmonia Mundi (HMM 90266970).

Suzi Digby included (amid much Tudor music and snippets of Contemporary) an enchanting, rarely heard RVW/Christina Rossetti part-song entitled 'Rest'. But above all, her vigorous, highly motivated ORA Singers gave the premiere of that surprisingly credible, arresting choral arrangement (by Greg Murray) of Vaughan Williams' Tallis Fantasia, mentioned above. An excrescence? Or a success? Definitely the latter.

Of yet more importance were two contributions by the Cheltenham-based period instrument Corelli Orchestra. Founded and directed by Warwick Cole, himself an outstanding and bewitchingly eloquent cello soloist, its major innovation was performing, in Cirencester Parish Church ('St John Baptist') the fascinating Passion setting by Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel (1690-1749), a little known - a proportion of his music appears to be irrevocably lost - almost exact contemporary of Bach - but unlike him, also a substantial composer of operas - whom Cole has unearthed, edited and now championed.

Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel

Like many Passion settings of the period it bears a fuller title, here Die leidende und am Kreuz sterbende Liebe Jesu (Our beloved Lord Jesus' suffering and death upon the Cross). Cole's vocalists were members of a young Oxford choir, the notably proficient Selene Consort, and each of the contributions - most importantly the Evangelist (expressive and evocative, the role shared between more than one voice) was largely appealing. The recitatives, not least, were competent, thanks to some sensibly mixed, often brisk pacing. As striking is the lengthy text, a vast quantity of bitingly effective rhyming patterns ('treten ... beten', 'nerzen ... ergötzen', 'Ritzen ... spritzen', 'Todes-Stoß ... Arm und schoß' - amounting to quite a linguistic marathon. The instrumental forces, while a modest deployment suffices, offer ample opportunities for occasional woodwind obbligati, from oboe or flute; Cole's harpsichord both supplied leadership and embraced reflection.

A focal element, not surprisingly, is the series of choruses, described as 'The Christian Church', which departs from the Bachian practice of calling on the same Easter chorale (most famously, 'O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden'), so as to furnish greater variety. The blend was surprisingly good, given the blatant, indeed pleasing, individuality of the half-dozen voices.

Bach himself conducted Stölzel's Passion in Leipzig in 1734, and where it most obviously breaks out into its own musical language is in a wonderful section, taken almost lentissimo, 'My gnawing conscience' ('mein nagendes Gewissen') - immensely atmospheric and moving, all the more so because the devotee's self-castigation comes between Peter's denial and the violent reactions of the virulent priesthood. Later choir passages have some of the vivid liveliness of, say, Praetorius' Christmas music. And more surprisingly, nearer the point of Christ's death ('So stirbt Jesus zwar ...'), and not necessarily just at the dramatic moment of the rending of the temple curtain ('Des Tempels Vorhang ist entzwei ... Die Erde bebt, die Felsen Reisen ... Die Graber tun sich auf') - into which words of optimism are unusually intermingled. Like Bach's St John Passion, Stölzel's concluding scene is Joseph of Arimathea, although Bach adds Nicodemus, bearing unguents and spices.

The St John Passion was the Corelli Orchestra's other notable contribution. This was a truly uplifting performance, an unmitigated privilege to be present at, under the immensely perceptive conducting of Geraint Bowen, now twenty-two years into his tenure at Hereford Cathedral, where he assisted and then succeeded the legendary Roy Massey.

Bowen's soloists were of the highest order: it would be difficult to better the flexible, fluent, fluid, and massively intelligent, Evangelist of James Gilchrist, or the awesome insight Matthew Brook brings to everything he undertakes - not least at numerous Three Choirs Festivals (they would not be complete without him), here bitterly lamenting ('und weinete bitterlich' - an astonishing instance of corkscrewing-down chromaticism) - Simon Peter's betrayal of Jesus' trust, and a strikingly sympathetic Pilate: the narrative provides for this, but Brook delves so much deeper.

Bowen's chorus on the night was the three Cathedral Choirs - boys, girls, men. This tripartite ensemble, all three - Hereford, Worcester, Gloucester - so professionally prepared, meshed together in as many as four joint Evening Services. Especially valuable was a stimulating sung rediscovery, under Samuel Hudson, of a sophisticated, galvanising setting of the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis by Ruth Gipps (1921-99), a composer whose orchestral works are at last being brought onto disc by Chandos (CHAN 20078, 20161).

But the united cathedral choirs gave life to many other composers - David Bednall, Judith Bingham, Parry, Howells; and surely a welcome premiere from a new name, young William Harmer: a Robert Saxton pupil, latterly at the Royal Academy, whose output to date includes not just the dramatic ensemble piece The Whole Heaven on Fire; the astonishingly mature solo soprano four-minute cantata Hope Is The Thing with Feathers (wonderfully close to Tippett); the jazzily syncopated, thrusting orchestral piece Aurora; and a setting of Blake's The Tyger aptly directed at young performers; and - most cheekily - a bracing, ingenious string solo Fajita in the Fridge. Harmer is the delightful winner of this year's John Sanders Memorial Competition for Young Composers, and his Anthem Rejoice was performed by the three cathedral choirs under Samuel Hudson, sandwiched between the Responses and organ Toccata by Sanders himself, the much-loved and much-missed former organist of Gloucester Cathedral, and a composer of real quality. To all these the united cathedral choirs brought a wholly expected professionalism: enunciation, modulation, tuning; their efforts vastly enhanced by Jonathan Hope's fluent accompaniments and finely judged registrations.

In the St John this fabulously honed chorus' impertinence to Pilate is not noisy screeching, but wittily impudent and insulting. ('If he wasn't a bad'un - ein Ubertälter - we wouldn't have brought him 'ere, would we?') By their worst bit of insolence - they sense Pilate is striving to release ('loslassen') Jesus - they take risks ('thou art not Caesar's friend') and their snarling grows. By the time the chorus, as Roman soldiers, squabble over Jesus' raiment, their prestissimo was quite brilliant. The range of moods that Bowen delved into and prised out of his choir was yet another thing that rendered this Bach interpretation so superb, and such a highlight of the week.

With Gilchrist and Brook, Bowen made refined space for touches of rubato which further enhanced the emotive pull of numerous sections. Gilchrist has his own distinctive way of leaning into a passage of text, not just vocally but actually physically leaning as well, to make the most essential words stand out. He not only makes them sing; he makes sure not a sliver of meaning is missed. He is surely England's finest Evangelist bar none.

We were lucky to have two such finessed - and flawless - violins duetting for first Brook (who amid his pains of Peter and ponderings of Pilate also - a bonus - took the bass ariosi and arias, such as 'Betrachte, meine Seel ...', followed quickly - again nursed by top strings - and the deeply expressive tenor Anthony Gregory's riveting 'Erwäge ... blutgefärbte'. Surprisingly Pilate's most telling line - 'What is truth?' - didn't quite generate that shocked intake of breath it deserves and usually gets. Yet 'Behold, what a man!' ('Sehet, welch ein Mensch!') did. Likewise his at last decisive 'That I have written'. And in particular, Brook's 'Nach Golgotha!' was stupendous. So genuine, and poignant. He may invariably look like a Rugby second row forward, but his great personality seems able to conjure up any kind of emotion. He is a performer, every time, of such stature.

Yet we were taken to the very edge of our seats as the very arresting Jesus, baritone Gareth Brynmor John's gift for contrasting Christ's stance, amid all this dangerous hubbub, between sternly reproving and gently encouraging - riding serenely above it all to irreversible tragedy - and finally, poignant - contributed massively to this extraordinarily powerful and inspiring mix. The paired flutes for 'Ich folge dich' were as sweet and blithe as Rebecca Hardwick's soprano aria itself (charmingly described in the old Troutbeck translation as 'for treble', which of course yielded the brilliant Vienna boys on the Harnoncourt version). 'Ach, mein Sinn' (which denotes 'thought', not 'sin'), is one of the most astonishing (tenor) arias in JSB's entire Leipzig output; and here, from Gregory, fabulous. The elasticated spring only underlines the devotee's dilemma. The final chorus ('Ruht wohl') was as touching as the scintillating opening one ('Herr, unser Herrscher') had been. It draws down a curtain, as if a Mystery Play has concluded. Is it a pity Bach capped it with a final invocatory chorale (Angels ... death ... elation)? Just possibly.

Something which greatly entertained the following day was a rather sweet performance of 'The Happy Princess', a tweaking of the Oscar Wilde children's story about the bejewelled statue that wills itself to die rather than see people in his town suffer and starve. It's one of Wilde's most famous - not that a revision is needed: a Prince can as easily be sung by a girl as a bird. Paul Fincham was the composer, and the libretto was written by Jessica Duchen for Garsington Opera's Youth Company in 2019.

An attractive much earlier version, especially touching for its virtual leitmotif capturing the Prince's not so much happy as forlorn appeals to the busy Swallow, was composed by Malcolm Williamson in 1965. Both Garsington and the Three Choirs could do worse than look at his accompanying opera, Julius Caesar Jones. It would bring vast rewards.

Here the main word might - perhaps - be 'charming'. The staging - a large mass of eager child singers had to be housed behind and above, but each time they engaged with the action they brought delight. 'Green' seemed very prominent, one of the attractive visual touches. The director(s) contrived to cast a rather stolid, glum, perhaps troublingly dominant, though tender-voiced, Princess (Willow Burden), and to task an enchantingly acute, tiny, bat-like little flibbertigibbet of a Swallow (Lauren Tribe, a Gloucester Cathedral junior chorister) expounding so skilfully a tricky little rising musical phrase, with distributing the Princess's declining finery to the poor of the town.

Fincham's succinct score was the real key to its success: horn, clarinet, oboe, flute, plus sundry woodwind pairings, conjuring up lots of variety; at one of several magical points, piccolo and bass clarinet; flute and staccato horn for the birds' chorus; a trumpet in a kind of organum effect near the close; and (a kind of envoi) ensuing strings and piano lament. A few vocal solos - one boy exceptionally good - dotted around to good effect; some suitable rocking patterns and nippy syncopation for the chorus; and a lovely lullaby for all forces. The music worked fine for these little performers, and clear, detailed, enhancing leads from Nia Llewelyn Jones (Gloucester Cathedral's experienced assistant conductor) kept everybody confident and assured. A success, to that extent. Most of the scene joins were brought alive by music, although one stage, a birds' or swallows' gathering, was managed without. Arguably this, and the Princess's stolid, clumsily directed entrances and exits, were the only drawbacks.

It was Adrian Partington's attractive determination at the outset that this Gloucester festival should reach warmly out to as wide a community in the city as possible. Other child-related events? The capable, productive composer Robin Haigh, thirty this year, has had rather a (justified) hit with Three Little Mammoths, a half-hour piece for instrumental trio and narrator with a text by, or after, bestselling Irish author Eoin McLaughlin. The three instruments are flute, cello and piano, which are nicely placed to provide both variety and simplicity. The plum here was the narrator: none other than Ed Balls, former minister and Gordon Brown's long-time henchman. As so often with these unexpected castings, they can work a treat. Mr Balls gathered the children in like the old pro he is.

This was a morning concert, and so was 'Shipwreck!', an opportunity (as with the ORA Singers) to hear a range of largely rare repertoire from the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods, strings furnished with polish and finesse by the small (four part) Linarol Consort - not floorcleaner, but the name of a master craftsman and maker of superb renaissance era viols such as the group uses - with James Gilchrist reappearing to add solo voice, abetted by attractive soprano Héloïse Bernard. Embracing Josquin and a tiny fragment of the marvellous Pierre de la Rue, this concert skipped rather than sauntered through not just that well-known composer Anon (eight pieces), but Ludwig Senfl (one whole minute), Edmund Turges (?Sturges - c1445/50-1500 - also a bit special), Gilles Mureau (virtually the same dates), the very productive - and once exceptionally famous - Alexander Agricola (1446-1506), and a cuckooing Juan del Encina (again similar dates). Only Janequin - his bird-calls and snappy battle-sounds - was needed to render this a very full repast indeed. Certainly a revelation.

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra - which excelled in The Pilgrim's Progress - resurfaced the following night, when Adrian Partington revisited a very large - and rewarding - oratorio, if that's the right word, by Francis (John Dolben) Pott, born 1957. Its title, A Song on the End of the World, stems originally from the first of the texts it occurred to the composer to set: 'On the day the world ends A bee circles the clover', which goes on in increasingly expressive vein, and is by the great Polish twentieth century poet Czesław Miłosz (1911-2004, but here writing in shattered and beleaguered Warsaw towards the end of World War II).

Francis Pott

Pott expounds his text so as to share a different kind of vision, moving away from a formal, or even informal, Christian viewpoint, while by no means jettisoning all. A word he uses. 'sceptic', suggests a kind of humanism might have a role. But the aura of war hangs over several movements, and Christian imagery is not far away, for instance in a wartime poem by Mervyn Peake, allocated here to the full Three Choirs Festival Chorus ('O Mother of wounds ...' - note the capital 'M'), and maybe especially in part five, 'Gethsemane', by the twentieth century scholar and mystic Thomas Merton. Here Pott deploys strings, extra pianissimo, highly effective, evoking a deep pathos; indeed Merton's 'Slowly, slowly' might seem, from a salient comment in the composer's notes, to have recalled Wilfred Owen's 'Be slowly lifted up, thou long black arm ...'

Not surprisingly in a movement Francis Pott actually entitles 'War' there is some massive, explosive writing, highly apt and fitting for this equally massive chorus, led and sometimes driven to great heights by Adrian Partington. It occurs in the first part (the rebellious Expressionist German poet and playwright Georg Heym, 1887-1912; died aged twenty-four in a shiveringly tragic accident), in his treatment of that darkest of psalms, Psalm 22. (He will know Pelham Humfrey's sensational verse setting of the same words.) Above all, it occurs in a lengthy Owenesque passage by Isaac Rosenberg ('Maniac earth! howling and flying, your bowel Seared by the jagged fire, the iron love ...') which Pott concludes with a profoundly sad woodwind fade ('We heard his weak scream, We heard his very last sound, And our wheels grazed his dead face'). The moment here, and the sensitivity of Pott's setting throughout, has a magical impact.

We seem no less far from Wilfred Owen in Randall Jarrell's words (Pott's 'Nocturne' movement): 'Strapped at the centre of the blazing wheel, His flesh ice-white against his shattered mask'. (Heym's death, incidentally, came from falling through thin ice.) 'His flesh ice-white' - pure Owen, those biting consonants, like Peake's 'sky-broken panes, and mirror's Fires ... Grass for her cold skin's hair' (a wild, skedaddling Allegro). Pott likes this kind of stabbing text, and very often achieves his best when inspired by it. Three lines of Dylan Thomas are just as savage - and it might be argued that this passion he feels for its sharpness and shattering is what holds the whole now almost quarter-of-a-century-old oratorio together. It is the work of a young man, but it doesn't in any way feel like that.

In that same penultimate movement, his alternation or intermingling of mezzo-soprano and baritone soloists (April Fredrick and Marcus Farnsworth, both dramatic, lucid and vitalising), renders it all the more striking. Serenity (initially almost pastoral) is reached in twenty-plus lines of Charles Causley; yet even this follows a probing thought from Traherne (four centuries earlier, although dead before forty) and is wrapped around two parts of the Christian Agnus Dei, almost as if (as he himself says) he cannot quite bring himself to break away. Do his doubts confuse, challenge, muddy the argument? That's what doubts are for. That's what Pott has striven to present. Were all the composer's intentions realised? A vast audience was there to will him on. This revival, conducted by Partington, was clearly a major hit.

It was James Hall who was the partner to England's supreme countertenor soloist Iestyn Davies - indeed some might suggest his equal - on Robert King's stunning Purcell and Blow recording, Elegy (VIVAT 118). Having him to play such a role in Graham Fitkin's The Age of Aspiration - an oratorio work clawing its impact from a host of scientific processes and theorems, chemical properties, lung contents, nitrous oxides and carbon monoxides - was surely inspired. Fitkin's stature as a composer is assured. It fell to Samuel West, as narrator, and the soloists (the other was baritone Dominic Sedgwick), to pour out the lung capacity, corked tubes and exit valves, Sodium and Potassium, copper and zinc, exhalation, philosophical jargon and political retrospect that made this text crackle on the penultimate night.

But the final evening was far more familiar fayre, the real thing: yet it was not always so. Elgar's The Apostles, from which Adrian Partington produced such an electrifying performance (from all the massed forces), was to a large extent as ignored, until the 1960s, as his earlier oratorios (Caractacus, King Olaf and The Light of Life) are still. But The Apostles (1903) has joined The Kingdom (1906) firmly and rootedly in the forefront of Elgar's supreme achievements.

The staggering research, in a very short time ('for a man of Elgar's magpie-like literary sensibility', as Richard Bratby's note reminds us), into preparing his own libretto - included (I didn't realise), Elgar's obtaining and exploring Wagner's incredibly detailed prose sketches, in the late 1840s, for an opera - a 'five-act-drama', Jesus of Nazareth, significant parts of which found their way, in spirit at least, into the Ring. Furthermore, Wagner's sketches, drawing intensively on the Gospels and clearly more than a few significant European theologians, reveal, it has been suggested, 'a level of theological sophistication which places him on a par with Johann Sebastian Bach ... I believe that had he brought the work to completion we would have one of the greatest artworks portraying the historical figure of Jesus of Nazareth.'

There was even a timely precedent: Mendelsssohn had moved beyond St Paul and (only just) Elijah to plot his own super-oratorio entitled Christus. Only fragments composed in his last year, 1846-7, survive, but it might have been on a par with - or outshone - Wagner's planned magnum opus. Picking up the ball, Franz Liszt's great (and long) oratorio Christus followed somewhat later - 1862-6 - and was not heard until 1873; César Franck's Les Béatitudes, a few years after that.

It was a matter of some months before Elgar amassed his text, composing passages along the way, to have it - or most of what he had intended - ready for Birmingham's 1903 Festival. Partington clearly had an inspiring grip on The Apostles - and of the Philharmonia Orchestra, albeit, given its vaunted official Three Choirs residency, only just returned the preceding night - from the massive ('Lento') start. It's crucial that he did, for that pianissimo opening chorus - 'The Spirit of the Lord' - demands insight, leadership and subtle control. The unnerving sound of the Jewish shofar (ram's horn), returning later for 'At the Sepulchre', is heard early in Part One, as the temple roof's 'watchman' welcomes the dawn (more chorus). This is complex music, and relies on careful nursing. It certainly got it.

By the time the immensely attractive tenor solo (Belfastian Michael Bell, like so many of today's outstanding male soloists an ex-Cambridge choral scholar (St John's College), acting as Evangelist (and also as St John), urged The Apostles' New Testament narrative on its way - Christ's choosing of his twelve disciples - this was already an exalted performance.

The Beatitudes are treated briefly, but touchingly floated. It is with these that the superb voice of Guildhall-trained bass-baritone Dingle Yandell - a founder member of the polished ensemble Voces8 - made its entry. A Fafner, Colline, Sarastro and Sparafucile - more bass- than -baritone, and perfectly cast as Jesus, he brought all the ingredients: soothing, caring, embracing, guiding, resistant, finally agonised, so truly wonderful. With a performance out of this world, Yandell made, it must be conceded, a somewhat fuller impact than Judas, even though John Savournin, the other bass-baritone (another Sarastro, and Leporello), won us over, if not quite to the traitor's side, at least to feel some empathy with him, and share his aching contrition, as Elgar clearly did ('Whither shall I go from Thy Spirit? ... Our life is short and tedious ... our body shall be turned into ashes ... our life shall be dispersed as a mist'), deftly underwritten by distant chorus, and extended over seven pages of vocal score. The fact that in despair Judas will finally commit suicide almost redeems him from his betrayal, which Yandell's sympathetic Christ patently foresaw.

Bell's navigating of the quite sharply chromatic Sea of Galilee preface was piquant, almost shivering. The great Mary Magdalene scene which follows, with mezzo Martha McLorinan a tremendous interpreter (along with Judas' penitence the most intense solo contrived by Elgar), inveighs music as forlorn as its text ('Help me, desolate woman, ... troubled spirit, soul in anguish ...'), which needs, with its downsliding sequences - 'deliver me out of my fear ... have pity, because I have sinned before Thee' - a deep sense of empathy. Partington, ever attentive to idiom and inspiring confidence - indeed perfection - from all parties, expertly prised from the Angels' exquisite 'Alleluias'! something as profoundly affecting as the Angel scene in Gerontius.

Adrian Partington, Artistic Director of the 2023 Three Choirs Festival at Gloucester. Photo © Michael Whitefoot

Aided by oboe and clarinet, the sopranos and altos excelled, most movingly; just as the divisi tenors and basses had an unexpected touching impact of their own ('We trusted that it had been He that should have redeemed Israel') - not censorious, but abandoned. This was after the searing, chilling sounds Elgar devotes to Christ's final words, offset by almost deafening stillness and silence. And as in the very opening bars of Gerontius, Wagner surfaces perhaps most obviously in these final scenes of The Apostles: Golgotha, and The Ascension.

An overwhelming success, then, and colossal achievement the whole week for Gloucester 2023. It will now be up to Worcester 2024 to match it. Yet it surely will. For one thing is certain about the Three Choirs Festival: year on year, full of miracles and marvels, it never fails its audience.

Copyright © 10 September 2023

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK