- Karl Amadeus Hartmann

- sexuality

- Provincialii

- Eugene Tzikindelean

- Butterworth: Six songs from A Shropshire Lad

- Angelo Simos

- Mozart: Jupiter Symphony

- Megaron

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

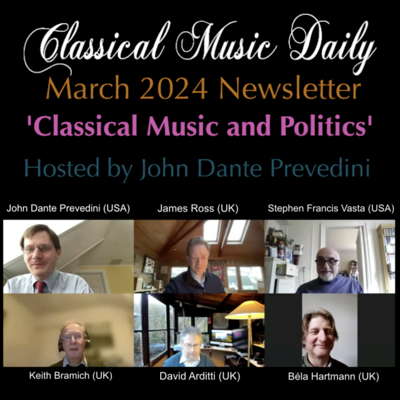

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Politics, including contributions from Béla Hartmann and James Ross.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Politics, including contributions from Béla Hartmann and James Ross.

Looks like we got ourselves a reader

No beating about the bush today. Just like tea and milk, melody and harmony, November skies and nostalgia, books and music have always been intimately entwined for me and as today is World Book Day, with the predictability of a bad soap opera script I have simply chosen five wonderful but seemingly not very well known pieces of music that owe their inspiration to a literary source.

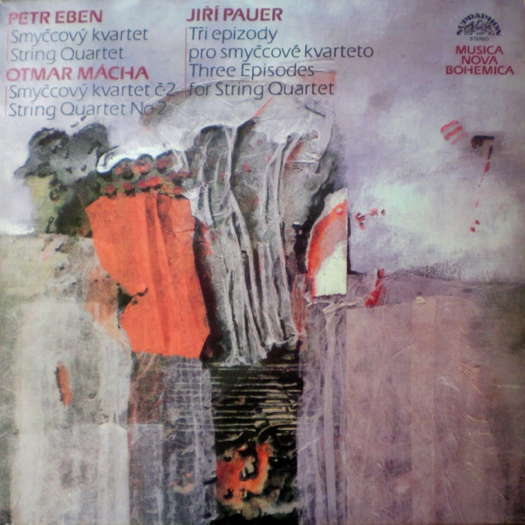

1: Petr Eben (1929-2007):

String Quartet (1981)

The best job I ever had was when - under the auspices of the European Union's Comenius programme - I was asked and tasked with giving lectures on Irish language, literature, history and politics to groups of secondary school English teachers from all over Europe. The subject matter of this undertaking was enormously more attractive than what usually paid for my daily bread at the time; the Comenius connection was the coup de grâce. The teachers came from The Netherlands and from Russia, from Finland and from Bulgaria and from all parts in between, except, of course, for the United Kingdom. They were the most attentive, enthusiastic and appreciative students I ever had the pleasure to teach. It says something about European Union - or lack of - that very few people I have ever met - Czechs not included obviously - have ever heard of Comenius or to give him his birth name Jan Amos Komenský.

Bohemian genius Petr Eben found lifelong inspiration in the works and ideas of his Moravian brother. His only - sadly - string quartet bears the subtitle of one of Comenius' most popular works and one of the greatest book titles ever: Labyrinth of the world and paradise of the heart, which Czech manages to say in five beautiful words, some without recognisable vowels as is common in that language: Labyrint světa a ráj srdce.

I once met, completely by chance, a great Czech violinist whilst walking in Madrid's Casa de Campo one January afternoon and he tried to teach me, with little success but much hilarity, how to pronounce such words. Comenius' title also serves to give some sense of the breadth of expression and varied richness of textures that Eben manages to create in this great piece.

Petr Eben; Otmar Mácha; Jiří Pauer. © 1987 Supraphon

2: Mátyás Seiber (1905-60):

Three Fragments (1957)

Humphrey Searle: Symphony No 1; Matyas Seiber: Elegy for viola and small orchestra; Three Fragments. © Decca Records

Humphrey Searle's The Riverrun to which I dedicated From swerve of shore to bend of bay is along with this piece my favourite musical setting of Joyce's words and Joyce's worlds. Indeed on a given day and mood this work may even surpass the Searle in my estimation or simply in the pleasure it brings. Mátyás Seiber called the work a chamber cantata and that's what it is. The fact that he manages to create such lavishly rich textures with such limited means at his disposal is just one of the many breathtaking aspects of this piece. The words Seiber chose when not actually about music are, for the most part, extremely musical in themselves. The music seems merely to delicately clothe in sound and evocative atmosphere the subtle seduction of Joyce's young, supple, suggestive words. This applies to the outer movements.

The central movement is violently different; being as it is a setting of Joyce's memory of a terrifying sermon graphically depicting the End of Days. Thanks to sermons like these hell was more viscerally real to me than heaven or earth all through my childhood. When I first read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man as a young man, reading this part of the book brought back in all too lurid and hellish detail those childhood feelings of total terror which I thought I had gotten over. It took me several attempts to read through this episode in its entirety before I was able not to have to break off, put down the book, stick my head out of a window and gulp oxygen as I squirmed through panic attacks and flushes of prickly heat.

The final movement in its evocation of tumescent drowsiness is pure magic. The sustain of the vibraphone in harmony with his vibrating aroused adolescent consciousness; the humming chorus echoing the blood humming through his veins; the strange new chords played by the strings as his soul swoons into a new world; the rocking repeated ebb and flow of a semitone as a tide flushes and floods within him, the way the bass clarinet is literally gently snoring as the piece slides into silence. It all amounts to some of the greatest word painting I have ever heard.

One last amazing aspect of this work is that it is as fully serial in construction as any piece I know well enough in order to say such a thing with any confidence, but as such it totally belies the idea that serial music has to have a particular sound. Serial it is but there are few pieces I know that are as simply and as sensually beautiful as Seiber's Three Fragments. Coming as it does towards the end of his all too short life, this extraordinary work only leaves one sadly speculating as to what might have been if Seiber had not met his end thanks to that greatest weapon of mass destruction: the motor car.

3: Alice Samter (1908-2004):

Four Morgenstern Songs (1954)

Alice Samter spent twenty-five years of her adult life working as a school teacher. Had she been born a man with equivalent musical talent, it is hard to imagine that she would have been anything other than a full-time, professional, admired and respected composer, but she was born a woman. Or maybe she just decided that teaching was what she really wanted to do. She is not here so I can't ask her. Just like Igel and Agel, Morgenstern and Samter seem made for each other. Mr Morning Star may have written a lot of what seems like harmless nonsense but he was no fool and Samter clearly had a very keen sense of humour but was no clown.

In a world seemingly ever more insane, nonsense of Morgenstern's calibre may be an ever greater repository of truth; something the original Dadaists understood. Indeed the fact that Morgenstern's name can also be translated as tomorrow's star serendipitiously hints at his possibly visionary Weltanschauung. How many would interpret a bird's behaviour as an expression of its thirst for knowledge? Samter's settings seem to hint at this or maybe that's just the power of her music causing me to fly away on my own flights of fancy. She manages, for example, to conjure up an incredible amount of pathos for the tale of the abandoned shirt in Das Hemmed.

This music is powerfully direct but not simple. It got under my skin at the very first hearing and it has been burrowing down further ever since.

Alice Samter: Kammermusik. © 1982 Mars

4: Arthur Honegger (1892-1955):

Phaedre (1926)

This piece for me is Arthur Honegger's best kept secret. It is incidental music he wrote for Gabriele D'Annunzio's - who we last met making love to summer in What's in a number? - play from 1909. The same tragedy also served for Pizzetti's opera of the same title first staged in 1915. The music Honegger produced for his version is far more impressive and unique than the Pizzetti in my opinion. It is music that owes something to the most mysterious Stravinsky but it inhabits a soundworld all of its own for me. Austere, angular, dissonant, it makes wonderful use of low winds juxtaposed with high strings. It creates a very specific and entrancing harmonic universe.

A Honegger: Symphony No 2; Phaedre

For those of you who don't know the story I won't go into it except to say that it is another tragic example of a Classical Greek classically dysfunctional family. For once for a yarn involving our Olympian fornicating forebears there is no sex but that's the very root of the problem. This particular recording also gives me a chance to pay tribute to great Russian conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky. Unlike some conductors who - doubtless through being so busy being masestros - are too lazy to learn new scores, Rozhdestvensky performed and recorded an extraordinary - indeed at times it beggars belief - amount of repertoire much of it very little known for which I am very grateful. This LP being a perfect example.

5: Fartein Valen (1887-1952):

Le Cimetière marin, Opus 20 (1934)

I started with a great European in Comenius and I shall finish today with another. Fartein Valen spoke at least half a dozen European languages fluently. He was a devout Christian who read his New Testament in the original Greek. But despite his ability in and love of languages he devoted himself to the language of music. He was saturated in the atmosphere and knowledge of the past but he was true to the times that destiny had dealt him even in the face of almost total scorn and ridicule from his peers. Like one of those roses he so lovingly cultivated on the shores of the far North Sea he resisted in stoic calm everything that was thrown at him. Indeed surrounded by mountains and fjords in his humble farmhouse, the sound and fury of contemporary music polemics probably seemed to him like so much idle chatter of no greater import than the screeching of seagulls. His dissonant counterpoint owed as much to Palestrina and Bach as it did to Schoenberg.

This piece is a great union of Europe north and south. Written by Paul Valéry; a child of the blinding Mediterranean, Valen first discovered this extraordinary poem in a Spanish translation whilst on holiday in Mallorca. As he said Valéry's evocation of his churchyard by the sea made Valen think of a churchyard back home in Norway used to bury cholera victims. This piece is not a setting of Valéry's words but a purely orchestral poem inspired by reflections on our mortality. Purely orchestral it may be but it says quite enough just as it is.

Fartein Valen - Contemporary Music from Norway. © Philips

As for Valéry his Le Temps scintille et le Songe est savoir is as poetic and perfect an encapsulation of the magic, mystery and meaning of music as I can think of.

Copyright © 23 April 2023

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain