DISCUSSION: Defining Our Field - what is 'classical music' to us, why are we involved and what can we learn from our differences? Read John Dante Prevedini's essay, watch the panel discussion and make your own comments.

DISCUSSION: Defining Our Field - what is 'classical music' to us, why are we involved and what can we learn from our differences? Read John Dante Prevedini's essay, watch the panel discussion and make your own comments.

- WCCMF

- Lars Vogt

- National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain

- Sarasate: Carmen Fantasy

- Santa Maria di Loreto Conservatory

- Bach Cello Suites

- Frank Zielhorst

- Crown Imperial

25 YEARS: Classical Music Daily celebrates twenty-five years of daily publication with an hour-long video featuring some of our regular contributors.

25 YEARS: Classical Music Daily celebrates twenty-five years of daily publication with an hour-long video featuring some of our regular contributors.

Gluckian Reform

GIUSEPPE PENNISI reports on a very special 'Alceste' which effectively closes the opera season of the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma

On 14 October 2022, the 2021-2022 season of the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma ended with the last performance of Alceste by Christoph Willibald Gluck, in the French version of 1776. There are two titles still in program – Giselle by Adam and Tosca by Puccini – but these are repertoire works already seen several times by a loyal audience. Not so Alceste. It is only the fourth time that it has been produced and staged in Rome. I remember that in 1967, the last time it was presented at Teatro dell'Opera, the capital's two major newspapers dedicated a page each to the event, signed by their authoritative music critics, Renzo Rossellini and Guido Pannain. Therefore, a rarity whose Roman representations have grown in success as they proceeded until they reached a sold out and real ovations at this last performance.

This second opera of the 'Gluckian reform', after Orfeo ed Euridice and before Paride ed Elena, was first performed unsuccessfully (in Italian) at the Burgtheater in Vienna on 26 December 1767. A shorter version of the opera, to a French libretto by Le Bailly du Roullet, was presented at the Paris Opéra on 23 April 1776. Today the opera is represented in the revised French version even though often translated into Italian. Both versions are in three acts and not in the usual two acts of the 'serious operas'.

When the score of Alceste was published in print in Vienna, in 1769, Gluck added a famous preface in Italian, almost certainly written by Calzabigi. It constitutes the real manifesto of their ideas on the reform of opera. The programmatic points follow those expounded by Francesco Algarotti in his Saggio sopra l'opera in musica (1755). These are: a) no aria with da capo; b) no space given to improvisation and vocal virtuosity; c) no prolonged melismatic passage; d) prevalence of syllabic singing to make words more intelligible; e) few textual repetitions; f) attenuation of the gap between recitative and aria; g) limiting the number of recitatives; h) accompanied recitative instead of dry; h) melodic simplicity. A symphony must anticipate the musical themes that will be present in the course of the work or must in any case be connected to the general atmosphere with the work to which the listener is about to attend.

The manifesto marks the transition of Baroque opera to classical and neoclassical opera. Today, after so many styles over the decades, the manifesto may seem simplistic, but Alceste remains one of the best examples of musical theater on conjugal love. In the tragedy of Euripides, daughter of Pelias and Anaxibia, Alceste stands out among the Peliades (who were, at least according to one of the most popular sources, Pelopia, Medusa, Pisidice and Hippotoe) for beauty and piety. She does not take part with her sisters in the dismemberment of their father, to whom the Peliades allow themselves to be induced by Medea, who promises them to return the old Pelias to new youth. Among his many suitors, Admetus alone succeeds with the help of Apollo to satisfy the conditions set by Pelias to obtain the damsel, namely to yoke a lion and a wild boar to the chariot.

Alceste thus becomes the bride of Admetus and a loving and faithful bride to the point that, Admetus having arrived in the prime of his life at the point of having to die, she alone offers to die for him. Admetus, to whom this privilege had been obtained by Apollo, is saved. According to a version attested to us by pseudo-Apollodorus and Hyginus, Heracles would have even descended into Hades to bring Alceste back to the world. The events of Alceste were often represented in drama and figurative art. Among the most famous figurative representations of the myth of Alceste is that of a relief on a sarcophagus of Villa Albani near Rome. Alceste passes among the virtuous heroines of antiquity together with Penelope, Evadne and Laodamia.

The musical work faithfully follows the myth but emphasizes the love between Alceste and Admetus. Alceste is Marina Viotti, a velvety mezzo, especially rich in long recitatives; young, she also shows that she is a skilled actress.

Marina Viotti in the title role of Gluck's Alceste at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2022 Fabrizio Sansoni

Admetus is Juan Francisco Gatell; he kept the ringing he had when he took his first steps at the Rossini Opera Festival.

Juan Francisco Gatell as Admetus and Marina Viotti in the title role of Gluck's Alceste at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2022 Fabrizio Sansoni

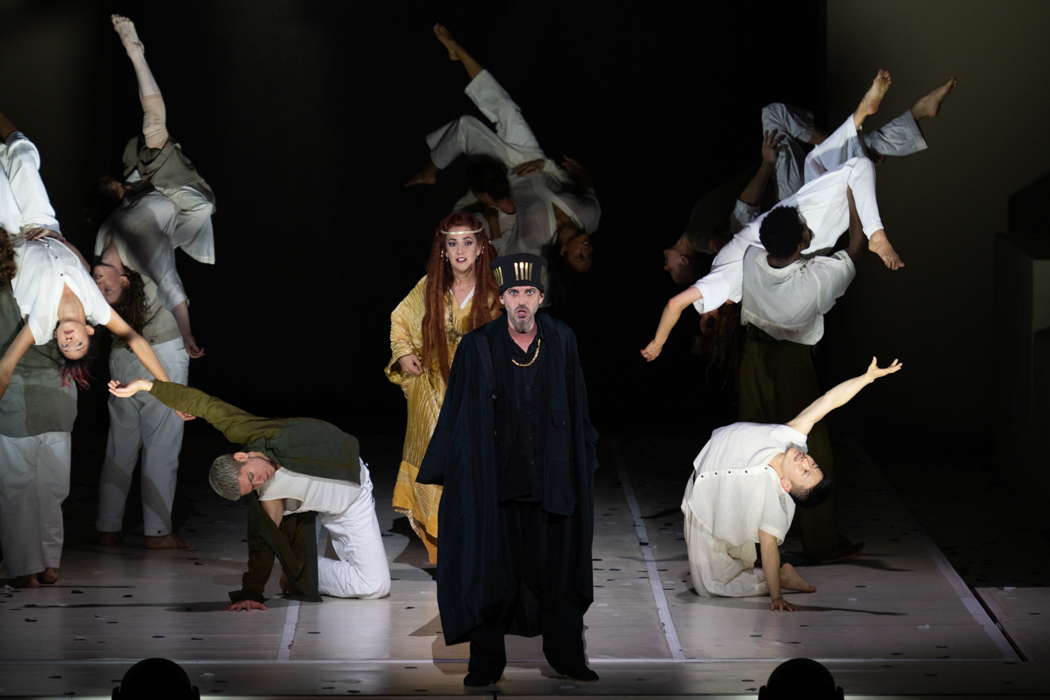

The direction and choreography by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui using the dancers of the Eastman group of Antwerp and the dance school of the Opera House was very intelligent.

Marina Viotti as Alceste with the dancers of the Eastman Group of Antwerp in Gluck's Alceste at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2022 Fabrizio Sansoni

The sets (Henrik Ahr), costumes (Jan-Jan Van Essche) and lighting (Michael Bauer) were fascinating. Gianluca Capuano conducted with a light touch. The chorus was prepared by Roberto Gabbiani; with this production, he leaves his position in Rome. When he appeared on the stage he received well-deserved ovations.

Copyright © 17 October 2022

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy

TEATRO DELL'OPERA DI ROMA ARTICLES