- Carbonelli

- Festival O

- Charles Harrison

- Church of St Augustine

- Malmö

- Hans Adolfsen

- Roberto Recchia

- Choir of the Miskolc National Theatre

VIDEO PODCAST: New Recordings - Find out about Adrian Williams, Andriy Lehki, African Pianism, Heinrich Schütz and Walter Arlen, and meet Stephen Sutton of Divine Art Recordings, conductor Kenneth Woods, composer Graham Williams and others.

VIDEO PODCAST: New Recordings - Find out about Adrian Williams, Andriy Lehki, African Pianism, Heinrich Schütz and Walter Arlen, and meet Stephen Sutton of Divine Art Recordings, conductor Kenneth Woods, composer Graham Williams and others.

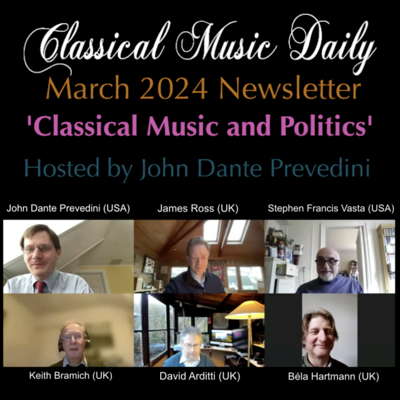

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Politics, including contributions from Béla Hartmann and James Ross.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Politics, including contributions from Béla Hartmann and James Ross.

A GOLD MINE

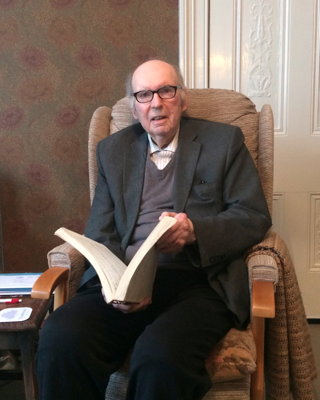

RODERIC DUNNETT visits Birmingham

to talk to John Joubert

to talk to John Joubert

Who is John Joubert? A French pop star? A Belgian polar explorer? A Dutch wood importer? A Mali desertification expert? A teenage serial killer?

None of these. John Joubert, South African born and a naturalised Briton, is one of the most eminent, sensitive, creative and perceptive composers working in Britain today.

He is not a new name, still in his twenties. Nor is he one of several composers like James MacMillan, entering middle age. Joubert, born on 20 March 1927, and a senior figure in British music, is now approaching his ninety-second birthday, and even if a little rickety on his feet, as my editor Keith Bramich and I discovered when we visited him for a congenial and insightful discussion in his adopted home of Moseley, Birmingham late last year, he is as lively, as wise, and as acute as ever.

|

Joubert is also one of the most beneficial and heartening of teachers: many aspiring young composers have been encouraged by him to nurse their talents and emerge as successful figures in their own right. His methods, so they tell me, at Hull and later as Reader in Music at Birmingham University, have been always generous, but also - as they should be - demanding. The work of his students has mattered to him as much as his own composition.

He has supported each in his or her chosen musical path, not interfering with their preferred style, merely sharpening it and enhancing its articulacy. He shows them how to better their handling of material, to tighten their structural approach, to finesse their orchestration so as to speak with greater clarity. Joubert is an inspiring guide, a stimulator, an originator, an overseer and an enthusiast.

It is the misfortune of some, perhaps many, artists and musicians that they become so well known for one, two or three particular works, that the riches of their oeuvre as a whole gets partially mislaid. An ample output need not mean an ample following.

Several of John’s near-contemporaries - Kenneth Leighton, Malcolm Williamson, Thea Musgrave, Gordon Crosse, and others - became somewhat eclipsed by William Glock’s cutting-edge focus at the BBC, and by his overdue but slightly blinkered advancement of the ‘Manchester School’ and others. Yet it’s worth noting that in this much more welcoming era since the 1990s, which does not see tonality or even modest modalism as outdated or unacceptable, the same can happen even to those masterly in-your-face Modernists.

Where are Xenakis, Dallapiccola, Skalkottas, Morton Feldman, Ferneyhough in our current concert programmes (apart from pioneering Huddersfield)? John Joubert is easily best known for his glorious carol Torches!, sung countrywide and beyond (in both unison and SATB forms); for its partner O Lorde, the maker of al thing; or for There is No Rose. All, note, are church music. John has composed some eighty sacred settings over six decades. Mention Joubert, and almost everyone knows these.

Yet the once know-it-all Moderns - witness Maxwell Davies’ famously self-justifying article in a 1956 edition of The Score - can latterly suffer this setback too. It is Davies’ fate to be known for Farewell to Stromness and 'Lullabye (sic) for Lucy' - essentially tonal works - to the ignoring of his far more important and more brilliantly complex output. Even his utterly beautiful early school masterpiece, O Magnum Mysterium, is scarcely done today. Ludicrous. Likewise that fine Schoenbergian Sandy Goehr has been largely outstripped by today’s younger generation.

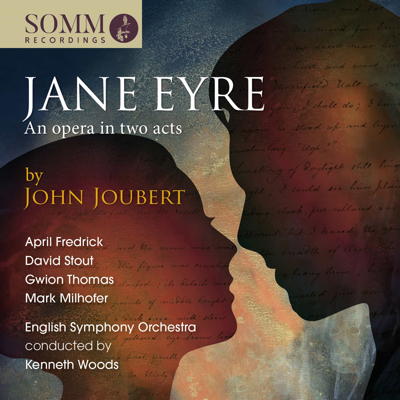

These are major figures of our country’s artistic life. And John is one of the finest of all. Thanks to recordings that are gradually, sometimes belatedly emerging, we can hear and relish his symphonies, string quartets, a handful of concerti, works for solo instrument, even his latest opera Jane Eyre, the first full performance of which (with David Stout as Rochester and April Fredrick as Jane) proved it patently a masterpiece.

|

It whets the appetite for more: what is to be made of his In the Drought, or Silas Marner, or the incredibly powerful Under Western Eyes? Of the fifteen minute Rorate Coeli Desuper? Of the South African works like South of the Line?

Joubert does not refer often in his music to South Africa, but the allusions are there. John is descended, he told us, from French Huguenots (hence the surname), as well as Dutch forebears. Already introduced to music by his mother, and progressing with lessons from an African naturalised former British composer, he gained added encouragement from his school music teacher who was, as it happens, a former assistant organist of Worcester Cathedral, and who knew his stuff. He has kept in touch with South Africa: his cantata Urbs Beata celebrated the completion of St George’s Anglican Cathedral in Cape Town, started in 1901, in 1963.

By 1946 he was ready to face the wider world and England, as for Williamson, was his natural destination. It was the PRS (Performing Right Society), he says, who made this possible, awarding him a scholarship just after the war to study there. (Paris and Nadia Boulanger might have been another destination, but the scholarship was designed for London.)

One of the first treats, he tells us with relish, was the chance to hear great music played by the major London orchestras under conductors such as Beecham, Furtwängler and Bruno Walter. Was Mahler already creeping into the metropolis’ programming? Only tentatively.

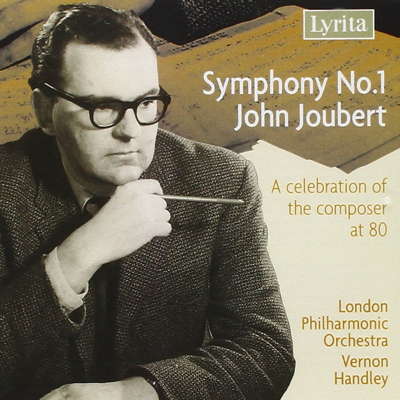

He gained an external BMus degree from Durham - then for curious reasons of academe the usual route to postgraduate or senior musical qualifications - which opened the door to a university career. That was answered by a lectureship at Hull University, a means of paying the bills but not a brake on his compositional flair. His first quartet, written almost immediately after arrival, and first symphony (1950 and 1955 respectively) were already making him a name in that less hothouse, more appreciative postwar era.

|

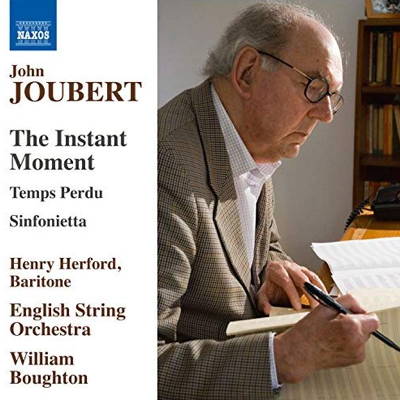

Nor did the outpouring cease when John transferred to Birmingham, first as lecturer or senior lecturer and later as Reader - in those days a title for assistant Professor. If anything, it increased. One area in which Joubert has enjoyed some marked success, in terms of performances (and his songs and cycles - think of The Instant Moment or The Secret Muse), has been his larger choral output.

|

The Martyrdom of St Alban (1968), The Magus (1976), his Herefordshire Canticles incorporating poems by Gerard Manley Hopkins and T S Eliot (and premiered at the Three Choirs Festival, commissioned by Roy Massey for Hereford in 1979; where Joubert’s Rochester Triptych also saw light of day in 1997), have all galvanised Midland audiences and indeed seen further performances.

Yet one wants to see them taken up far beyond: in the north of England, where strong choral societies abound; and of course in London, and abroad.

Jeffrey Skidmore and Birmingham-based Ex Cathedra commissioned South of the Line, a fascinating treatment of Thomas Hardy poems encapsulating (before Wilfred Owen) the bitterness and tragedy of war, and including ‘Drummer Hodge’, used by Alan Bennett in The History Boys, which underlines the tragic death of young men, mere teenagers some, on both sides.

|

For the millennium, the ever-supportive Skidmore also commissioned Wings of Faith, another offering as delicate as it is weighty. The Gloucester Three Choirs Festival this summer, July 2019, will hear afresh, and hopefully marvel at, Joubert’s An English Requiem, premiered there in 2010.

I have long held that one of his best, easily, is Gong-Tormented Sea (1981), an (as I suggested to him) possibly unfortunately-named oratorio of real power, full-bloodedness and excitement. Again, it first saw light in Birmingham, and its central section (of three), ‘Rounding the Cape’, an excellent and evocative text by Roy Campbell, the controversial early twentieth century South African poet, linked Joubert again with his original homeland.

Another work that should be campaigned for, in my view, is (as mentioned above) Joubert’s Joseph Conrad opera Under Western Eyes. It was composed in 1968, a kind of annus mirabilis for the ultra-modernists. Yet what it proved, apart from its huge dramatic power, was that Joubert and other composers of this time - McCabe, Hoddinott and Mathias - are every bit as skilled in their scrupulous use of musical material - of fragments, of patterning, of Leitmotifs - as their Schoenbergian/Webernian-dazzled colleagues.

What Schoenberg writes, his brilliant advice, in Fundamentals of Musical Composition (in which many of his examples, tellingly, are from Brahms), could just as easily be applied to British composers who, maybe with the odd exception, are on no grounds to be seen as looser in approach than those adhering to the Second Viennese School.

The other thing it confirms, if it needed confirming, is what John told us, in our meeting, of his passion for literature. One might compare him with Arthur Bliss, another for a time somewhat shelved composer, whose library (when Lady Bliss showed it to me) was a miracle of insightful poetry in all languages, of the Greek and Roman Classics and the English classics alike, of novels whose spirit and wisdom he had absorbed and reiterated in a wide range of his works.

Joubert is such a composer. For a composer who has seen, almost as he left South Africa, the miseries of apartheid inflicted on his previous fellow students and fellow citizens, literature is surely a salve. A way of seeing the world differently. Of being a definitely humanist - with a small ‘h’ if not a large ‘H’ - figure.

The one thing that matters most, Joubert says, and has mattered to him since he began composing, is communication. It is his aspiration that his works, now and in the long term, will speak to many, to ordinary listeners, and will provide inspiration: an either religious or at least spiritual, and emotional, uplift.

|

Churches and cathedrals (I say) should be full of his music, as much as they are with that of Bob Chilcott or Gabriel Jackson from the present generation. Our obsession with ‘commissioning’ (although John has, as indicated, of necessity also benefited from that) must not let us lose sight of that which already exists. Of second, and third, performances.

Always, there are riches to be mined. Would it make sense to lose sight of William Mathias? Of course not - and Mathias’ largescale choral works are far fewer than Joubert’s. Does it make sense scarcely ever to see McCabe’s Edward II or two-part King Arthur ballets? They should be exported to - everywhere. Losing sight of them would be as stupid as treating as passé the films of Derek Jarman, or Ken Loach, or Sidney Lumet, or François Truffaut. Or bidding goodbye to Henze, or Poulenc, or Barber, or Hindemith.

John Joubert deserves better. Partly it is a matter of publicity, and John, like many composers, is modest, even shy, of outrageously courting publicity. He needs others to do it for him, and sometimes that does not mean publishers. Someone needs to beat the drum.

Maybe the web will help. The initial ‘John Joubert’ entries on YouTube feature interviews with ‘the Nebraska Boy Snatcher’, clearly seen as riveting stuff. Maybe our John should write a work on that subject.

But not far down comes O Lorde, the maker of al thing, his Divertimento for Piano Duet, his Third Piano Sonata, even his Piano Concerto and Violin Concerto (in full), his entire First Symphony (broadcast from South Africa), his Second Symphony (with the LPO) and his orchestral Déploration (note the acute) in memoriam Benjamin Britten (1978), another Birmingham premiere. The Raising of Lazarus, a fifty minute oratorio with Dame Janet Baker, no less, looks like a highlight.

|

Torches is there, of course, in various forms, noting that its text is translated from a Galician - ie north-west Spanish - carol; King’s College, Cambridge performs There is no Rose, and Guildford Cathedral, under the legendary Barry Rose, A little child is yborn. Even as modest an offering as a chant (for Psalm 84) from New Haven, Connecticut, or O Lorde, the maker of al thing sung by St George’s Cathedral, Toronto, and There is no rose from St Matthew’s, Ottawa - Pennsylvania, Georgia and California choirs also feature on YouTube - might confirm that Joubert is, to a degree, a known force on the opposite side of the Atlantic. There is even a tasty Italian consort from - of all places - Frascati.

As to the man and his continuing aspirations at the grand age of ninety-two, an interview with the Birmingham Post’s ever-acute Christopher Morley - listen: John Joubert interviewed by Christopher Morley - runs to nearly twenty minutes, focusing on John’s Jane Eyre, which he confirms to be his seventh (possibly eighth) opera. (Three are for children or young performers.) Of the full scale efforts, the one-act In the Drought (1955) screams out for a revival. So may Silas Marner, which, like Under Western Eyes, is a full three-acter.

Joubert’s compositions are a gold mine. To be put on a back shelf for some time in their latter years seems to be a fate that composers, to their great credit and courage, seem resigned to.

|

Listen — John Joubert: Allegro vivace (Piano Concerto Op 25)

(Lyrita SRCD367 track 3, 12:40-13:38) © 2018 Lyrita :

But the front shelf beckons, and if even Gustav Mahler can be ignored in Britain till the 1950s, or Berg - pace the 1930s concert premiere of Wozzeck conducted by (unbelievably) one Dr Adrian Boult - who knows what may await? Today’s mainstream may be tomorrow’s sidestream, but equally, today’s sidestream may be tomorrow’s mainstream. It would be my guess - and a good many may agree - that Joubert is on his way back in. How good it would be if that were true.

Coventry UK